views

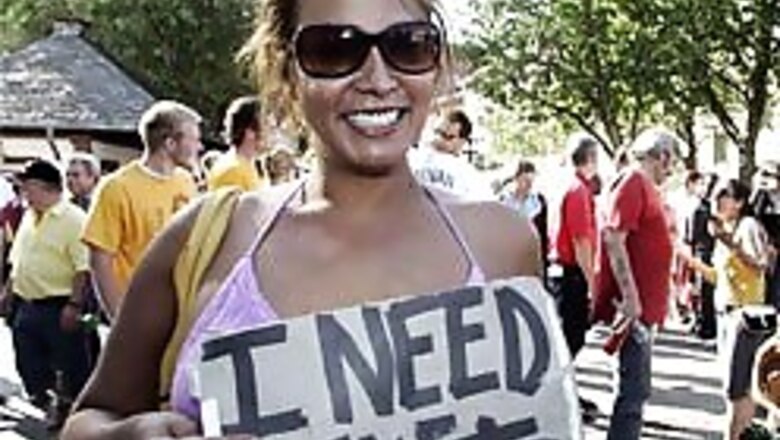

Hanover (Germany): They crowd stadiums and street festivals, rearrange their lives around game schedules - women are everywhere at this World Cup.

It's a long way from the days when soccer was strictly men's business and female spectators were an oddity.

The German soccer federation lifted a ban on women in the sport in 1970. Three years later, the nation's first female TV sports anchor was booed off the national stage by predominantly male viewers for getting the name of a Bundesliga team wrong.

The decades-long exclusion of female fans and players bred a backslapping, violence-prone male soccer culture that put off even more women, said psychologist Ursula Kessels of the Freie Universitaet Berlin.

But once the dam was breached, the women came to the sport in huge numbers.

Germany's national women's team is No. 1 in the world, ahead of the United States. The Germans won the 2003 World Cup and are six-time European champions. A women's Bundesliga was formed in 1991.

Today, 12 per cent of the 6.3 million members in Germany's soccer clubs are women. Soccer has become the No. 1 team sport for girls.

One of the young players, 15-year-old Johanna Friebel, helped start her own team with three close friends in the central German village of Schlangen.

She attends all home games of the nearby FC Paderborn, a second division club.

''More and more girls are coming to watch the Paderborn games,'' she said. With three girlfriends, she follows Germany's World Cup games on a large screen in Paderborn, and the other matches at home on TV.

Niels Barnhofer, a spokesman for the national soccer federation, hopes the World Cup, with its good-natured street celebrations, will attract even more women.

One high-profile fan is normally subdued Chancellor Angela Merkel, who has attended every Germany game and has been captured in TV closeups raising her arms in joy over a goal.

Yet in an interview earlier this year with Germany's largest tabloid, she had to prove her soccer credentials.

Asked by Bildzeitung if she knew the offside rules, she said she had expected such a question, then drew some diagrams for the journalists, passing the test.

''You probably wouldn't have asked a male chancellor this question,'' she admonished the journalists. ''I'm also sure many don't know the answer.''

A TV commentator wondered out loud about the absence of Merkel's husband, who stays out of the limelight and, according to the chancellor, doesn't care much about soccer.

PAGE_BREAK

Such role reversals would have been unlikely in the first two decades after World War II, when Germany rebuilt its shattered economy, but also was steeped in social conservatism.

Until 1970, the national soccer federation (DFB) banned female teams. Federation chiefs argued that the sport was too aggressive for women.

During the ban, a secret soccer culture flourished, with women organizing teams and even holding unofficial international games, said Juergen Nendza, co-curator of an exhibit on women in soccer.

In 1957, when the city of Munich provided a soccer field for such a tournament, it received an angry letter from the federation that it had ''undermined the federation's fight against ladies' soccer,'' according to the researcher.

Yet, by the late 1960s, fueled by the women's and students' movements, more than 40,000 women played soccer in Germany, he said.

Under growing popular pressure, the federation lifted the ban. Still, many men resisted the women's incursion into what they felt was their turf.

In 1973, state TV for the first time hired a woman as anchor of its Sportschau, the weekly summary of Bundesliga games and a national institution.

In her fifth appearance, Carmen Thomas, then 26, had an innocent slip of the tongue _ referring to a top Bundesliga club as ''Schalke 05'' sted ''Schalke 04.''

She joked about her error later in the show, but a tabloid unleashed a campaign against her, which has become part of German sports folklore. Today, several female reporters hold top sports jobs, including as TV anchors.

Barnhofer, the federation spokesman, said the DFB supports women's soccer wholeheartedly. Yet women's soccer is far from drawing level with the men's game.

On an average, a women's Bundesliga game draws just a few hundred spectators, compared with tens of thousands for the men.

Only a handful of top women players can make a living from soccer, including star striker Birgit Prinz, who in December was chosen FIFA's Player of the Year for the third straight year.

Even the best women won't get rich like some of their male counterparts, said Prinz's manager, Siegfried Dietrich.

Prinz worked for years as a physiotherapist and now studies psychology to secure her future. For about two years, she played in the now-defunct women's professional league in the United States.

When Germany's women's team became European champion in 1989, the players were rewarded with a set of dinner plates. Today, they get cash bonuses, though a lot less than the men.

Dietrich said the breakthrough for German women's soccer came with the national team's 2003 World Cup victory. He noted that last month's UEFA Cup final between two German teams, FFC Frankfurt and Turbine Potsdam, drew 13,000 spectators.

The manager said he expects another leap forward over the next decade. Large numbers of girls are joining clubs ''and we'll discover lots more talents.''

Comments

0 comment