views

Pollsters’ recent predictions giving the Trinamool Congress (TMC) a third term in Bengal have once again led to clichéd electoral wisdom being passed around: that people vote differently during the Lok Sabha and the Assembly elections. Further, it was argued that since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is organizationally weak and lacks a charismatic leader in Bengal, any claim to a saffron victory in the state, despite the party winning 18 of the 42 seats in 2019 Lok Sabha polls, is wishful thinking at best, and agenda-setting for the BJP at worst.

This narrative surprisingly continued even when many recent field reports revealed intense anti-incumbency in Bengal due to ‘corruption’ and the ruling TMC’s political repression across social groups. Armchair analysts then started discussing two social segments in particular, the Muslims and women voters. This echoed political strategist Prashant Kishor’s assertion that the TMC’s job is easier than the BJP’s as the former needs majority of minority (Muslims account for about 30 per cent of Bengal’s population) and minority of majority (Hindus account for about 70 per cent). Since Muslims were consolidating behind the TMC, experts argued that women, constituting around 50 per cent of the electorate, would veer more towards Mamata Banerjee, as she had a near-10 per cent advantage among them in the past elections.

This thread of reasoning is erroneous on two counts. First, the argument that a 30 per cent Muslim population translates into an edge for the TMC is flawed. It assumes that Muslims are uniformly distributed in the state when they are actually concentrated in parts of Bengal—Uttar Dinajpur and Malda in North Bengal and parts of Birbhum, Murshidabad and South-24 Parganas in South Bengal. Their electoral weight in a polarized election is decisive in only around 60-65 Assembly constituencies.

Second, the argument about Mamata Banerjee’s decisive lead among women is oblivious of the field realities. It commits the fallacy of treating gender as an unembedded and autonomous factor even in a polarized electoral ambience informed by anti-incumbency.

Top-down analyses, however, witnessed another shift after the first two phases of voting in Bengal. Thereafter, the debate has been less about who could win and more about the factors responsible for the rise of the BJP in Bengal. While every analyst has started accepting anti-incumbency as a key reason, a few still object to the invocation of subalternity and Subaltern Hindutva. Rather, they take recourse to the anachronistic elite theory of power, completely misreading the core characteristics of Subaltern Hindutva, and make a case that the shift of elites—the Bhadralok—to the BJP is the prime factor behind the rise of the BJP in Bengal.

What is Subaltern Hindutva

The concept Subaltern Hindutva was an outcome of my field studies in the Hindi heartland between 2009 and 2013. During this period while the BJP was witnessing an electoral decline nationally and in UP, the social outlook of Hindutva was gaining prominence among a large section of the subaltern. A closer scrutiny of this process revealed a shift in the political psychology of the Hindu subaltern, who felt left out under the secular or social justice parties.

Here, one may argue that this is nothing new; that many Hindu castes have an anti-Muslim communal outlook even if they keep voting for non-BJP parties that swear by secularism. In fact, RSS ideologue K.N. Govindacharya had openly outlined the Hindutva strategy of social engineering by late 1980s wherein OBCs (Other Backward Classes) were supposed to be the engine of the BJP’s march to power. One could also cite instances like a Dalit, Kameshwar Chaupal, laying the foundation stone for the proposed Ram Mandir at Ayodhya on November 9, 1989.

Academic work has documented these trends. Badri Narayan in his work Fascinating Hindutva: Saffron Politics and Dalit Mobilisation (2009), Ornit Shani in Communalism, Caste and Hindu Nationalism: The Violence in Gujarat (2007), Kancha Ilaiah in Buffalo Nationalism (2004), Christophe Jaffrelot in India’s Silent Revolution (2003), among others, have delved into the positive interplay between the Hindu subaltern castes and the Hindutva discourse. However, they all share the assumption that the subaltern shift towards the saffron discourse is primarily a result of the persistent work by Hindutva organisations, led by the Brahmanical castes.

Implicitly, they also share the assumption that the Hindu subaltern agency is gullible and co-optable by the superior and overarching agencies of the Brahmanical castes. The same scholars, however, tend to celebrate the Hindu subaltern as radical and assertive when she supports the discourse on reservation. This is a reductionist approach that doesn’t fully capture subaltern agency. It looks at the subaltern as both passive and agentive, but that depends on which discourse she supports.

Characteristics of Subaltern Hindutva formed the basis of my PhD research proposal at JNU in 2013. The key questions that I have since engaged with are:

1. Is the process of subalternization of Hindutva incidental or is it a product of political calculation by an active agency of the Hindu subaltern?

2. Will the OBC/SC joining the BJP/Hindutva discourse change the nature of Hindutva?

3. How does the trend of ‘consolidation of Hindu subaltern’ behind the Hindutva forces go hand in hand with another dominant trend of ‘intra-subaltern conflict’ among the Hindu community?

4. In what ways would it impact the nature of inter-community relations between Hindu-Muslim and the intra-community relations among the Muslims?

Since these questions were asked before the rise of Narendra Modi nationally, the emphasis was more on the shift in the societal realm. Further, the presence of the RSS and its affiliates in rural areas, barring a few pockets, particularly in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, has been negligible. Thus, its influence in causing the saffron shift of the subaltern is insignificant, unlike what is argued by Badri Narayan.

Rather, the shift was led by the political agency and transactional outlook of a section of Hindu subaltern castes, which felt that social justice parties were either catering to a particular caste that formed their core support base or the Muslims. This section came to the Hindutva table with a trade-off: it would see Muslims rather than Brahmanical castes as the common ‘other’, provided its constituents are given leadership roles and it acquires an indispensable position within Hindutva.

This phenomenon is what I call Subaltern Hindutva. It is the dominant political discourse in western, central and northern India, and has now made a remarkable entry in the east, including Bengal. It takes a constructivist approach of myth-building and argues that Muslim rule and a secular discourse centred on minority appeasement are responsible for their ‘precariat’ position.

Hence, Subaltern Hindutva is more transactional, less ideological. Second, it is not a saffron version of Ambedkarite discourse, which portrays Brahmanical castes as the common ‘other’. Rather, it defines Muslim as the common ‘other’ for a better representational and cultural space that Hindutva readily provides. Thus, Subaltern Hindutva doesn’t exclude the upper castes; rather it makes them an ally in its quest for power. The ‘subaltern vs elites’ binary doesn’t hold here. And, any attempt to conflate these two very different discourses is erroneous and mischievous.

Subaltern Hindutva and Bengal

The genesis of Subaltern Hindutva is in the sense of relative deprivation and the feeling of being left out under an apparently secular regime. Hence, anti-incumbency against a non-BJP regime—as seen in Bengal—is always the starting point for the shift in the electoral and political realm. Therefore, the chanting of slogan ‘Joy Shri Ram’ signifies both anti-incumbency-propelled popular disenchantment of the larger subaltern Hindus with the Trinamool government as well as their transactional fascination with Hindutva.

While a significant section of non-Kolkata Bhadraloks (NKBs) and other upper castes also respond to the BJP and Hindutva discourse, there is a difference of degree if not direction in their saffron support and its demonstration.

A significant number of TMC leaders joining the BJP is not the cause for surge in support for the latter, as top-down analysis would believe. They are shifting their allegiance because the ground has shifted. Their shift is the effect; Subaltern Hindutva is the cause for the saffron surge.

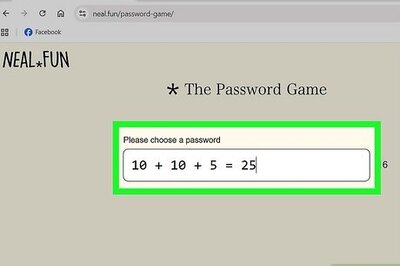

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment