views

On September 13, 2009, a few hours after the six-day-long agitation was called off by the pilots at Jet Airways, Naresh Goyal held out an olive branch. In an attempt to bury the hatchet and tell each other “let bygones be bygones,” Goyal, chairman of India’s largest airline, invited 200-odd pilots to join him for high tea at a five-star hotel near Mumbai International airport. But there’s a thing or two about relationships. They’re awfully fragile. And when fractured once, the demons are incredibly difficult to exorcise.

Which is why, when the pilots reached the venue and discovered Capt. Hameed Ali, who is chief operating officer (COO), Declan Conolley, vice-president (VP) flight operations and Capt. Hassan Al-Mousawi, senior VP-operations and on-time performance, already seated in the conference hall, they flew into a fit of rage. Never mind everything else you’ve heard about why they agitated in the first place. Call it xenophobia, call it imagined anguish, or call it real anger — to everybody’s embarrassment, not a single pilot would enter the hall until the expats in the room left.

Their gripe? That they take home $7,200 a month and are expected to fly 22 days during the time. Their expatriate counterparts, on the other hand, are paid $12,000 a month with taxes being picked up by the company; fly 12 days, take 10 days off when they get business class tickets to go home. This, the Indians argued, was discrimination. Over the last one year, they claimed they had tried their damndest best to reason it out with the three men now accompanying Goyal. If things had come to a boil, they believed the blame had to rest squarely on the shoulders of these managers. Eventually, Goyal conceded ground and the team of negotiators accompanying him left the place and he was left to himself to manage the evening.

Now, Naresh Goyal is the kind of man who has handled an incredible number of conflicts in his life in a manner that can only be described as infuriating. He simply avoids them. Two years ago, he told a colleague of mine that if he doesn’t like somebody in the organisation, he doesn’t sack them. He just gives them a newspaper. After three months of reading newspapers and with little else to do, they get the message and leave. But more importantly, it saves him the heartache. (Goyal declined to comment for this story.)

The trait was visible in October last year too when Jet Airways took a call to lay off 800 cabin crew. The perfectly manicured and well-coiffured crowd took to the streets, attracted attention by the truck loads and managed to attract the political munificence of Raj Thackeray who heads the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena. Goyal feigned ignorance and swore on his “dead mother” the decision was taken without him being in the know. And now that he knew about it, the crew would be reinstated. By all yardsticks, we know that was a stretch — but you get the general drift?

The problem is, the way things are at the airline, Goyal’s almost Sun Tzu-ish approach to conflict is the problem. On the one hand, there is his obsession and reliance on expat managers to run the place. In his mind, the reasons were obvious. Like he always says to anybody who cares to listen, to fulfil his dream of building an airline with the technical efficiency of Lufthansa, the on-time performance of Swiss Air, the service quality of Singapore Airlines and the accident free record of Qantas, he needs to hire the best the aviation business has to offer.

Be that as it may, his obsession with expats has stoked incredible anger within the ranks of his Indian managers who are convinced their careers have run into a glass ceiling. “It was frustrating that there were always foreigners at the top, who were always paid and treated better” says Nandini Verma, former VP, corporate affairs, who worked for 20 years with Goyal, and then quit to join Kingfisher.

An Obsessive Man

Don’t assume, even for a moment, that because Goyal avoids conflict, he is a wimp. The man is tough as nails, knows what he wants and will do what it takes to get what he wants. There was this time for instance, when upset at how the toilets were on a flight, he flew into a fit of rage and cleaned one himself to show the cabin crew how spotless the place ought to be. “I get into detail. That makes me passionate about my business, not a control freak,” he once said.

His “passion” pushed him into seeking out the “best talent” the world has on offer. That is also why when he started the airline 16 years ago, he was clear top jobs in the organisation would be manned by expats. This included that of the CEO, the COO and the head of engineering. His board was eventually packed with stalwarts like Vic Dunca who came from Philippine Airlines and Ali Ghandour, former chairman of Royal Jordanian who was advisor to the late King Hussein. Insiders at Jet privately joke that Goyal trusts his expat managers more than his wife Anita who runs sales and marketing for the airline out of her base in London.

PAGE_BREAK

Whatever the case be, the fact remains, in the early years, Goyal’s reliance on expats paid off. For instance, Nikos Kardassis, a Greek American who was the second CEO at the company, is credited with creating a global footprint for the airline though it operated only in India. He engineered code shares with dozens of foreign airlines which enhanced the upstart airline’s connectivity. Eventually, this translated into Jet’s dollar bookings (tickets booked by overseas travellers to India) being significantly higher than other carriers like Indian Airlines. These tickets were sold at much higher rates than tickets booked in India. Expat CEOs also helped build the foundation for making Jet the carrier of choice for business fliers. Jet’s carefully structured mileage programme was the envy of its rivals.

In that sense, all was well. Then something happened in June 2005 that rattled even seasoned veterans at the airline. One June morning, his A-team members woke up at their homes, picked up the newspapers and choked on their coffee. Headline writers in newsrooms across the country had gone crazy over Goyal’s decision to order 20 new wide-bodied aircraft at the Paris air show. Goyal told the goggle-eyed media that these planes would be inducted into the airline’s fleet over the next 18 months to propel his aspirations of taking Jet global — that he wasn’t content with being a domestic airline anymore.

Until the papers wrote of it, nobody at the airline — not the CEO, not the COO, not the board of directors — knew this was coming. They were horrified. There was no way in hell the airline could be readied to manage the complexity of running international operations in the frame Goyal wanted. It had just begun flying to London after years of lobbying and maneuvering through bureaucracy — thanks largely to the tenacity of Saroj Datta, the 73-year old executive director, and one of the few Indians at the airline Goyal trusted.

But for Goyal, this was the big moment. For a man who started life working as a flunkey at his uncle’s travel agency in Delhi, this was what he had waited for all his life — to build a global airline and take on the best in his business like Singapore Airlines, a company he was always in awe of. A premium, full service carrier with an incredible business class offering, it attracted upscale businessmen and executives willing to pay extra dollars to fly. If getting there meant replacing the heads of various departments with expats, he didn’t flinch. In one swoop, finance excluded, expats were brought in to man key positions.

In a matter of weeks, the six Indians managing in-flight services, airport services, corporate affairs and the head of its Asia-Pacific operations left in a huff. “The resentment against foreign pilots is deep-rooted and goes beyond the events of the last two-three years,” admits Saroj Datta. In the years that followed, Jet inducted close to 400 foreign pilots, almost 40 percent of its total strength. They came from the US, Columbia, Romania and so on. Airline folk derisively referred to Jet as the UN of the industry.

Not that Goyal cared. As far as he was concerned, his ever growing cadre of expats was a badge of honour to be worn proudly. No other Indian company had bet on a diverse a talent pool as he had. He spoke proudly of how his vast network was employed to hunt for the best people, wherever they were. In some sense, it had become a bit of an obsession. So while Goyal, with his pronounced Punjabi accent, exuded a rustic charm, his expat managers became his sophisticated, public face in global forums or to raise Rs. 1,899 crore for a hugely successful IPO. “CEOs are handsome. Entrepreneurs are ugly,” he once said and roared with laughter.

Gaurang Shetty, senior vice-president, is one of the few Indian nationals in Jet’s top rung. He says the discipline, practices and experiences expats introduced benefited the airline tremendously. “Growth was exponential over the years,” he says. “The issue was how to manage this growth,” Goyal, he says, had two choices. Either get in global talent or nurture people from within. He opted for the former.

Starting in 2005, Jet planned operations at a dozen international airports all the way from Brussels to San Francisco. “No one had heard of the airline in these markets. And it meant negotiations with dozens of vendors, suppliers and airports. We needed someone who understood this and did this regularly,” says Shetty, stoutly defending Goyal’s choices.

Grapes of Wrath

Even as Goyal kept carving one victory after another, there was something creeping up behind him. Simmering discontent in the ranks and low cost airlines, an idea he has always dismissed condescendingly. Both of which, he was blindsided to.

PAGE_BREAK

For various reasons, he had always maintained that in India, low cost carriers wouldn’t work. He was wrong. They did. The numbers proved it. And when the global downturn hit home towards the end of 2008, passengers shifted en masse to the lowest cost options they had. They were simply unwilling to pay more to fly on a full service, premium carrier like Jet and Goyal was compelled to do a U-turn.

At the company’s annual general meeting in August this year, he acknowledged “Demand for premium class travel is declining and the air travel market has become price sensitive. We have introduced low cost travel on routes where there is sluggish demand for premium travel.” Earlier this year, Goyal quietly launched a low fare brand called Jet Konnect with Sudheer Raghavan, a veteran at Singapore Airlines and a citizen of the city state, at its helm. Goyal ignored the sniggers it attracted because Raghavan had never run a low-cost airline in his career.

The way things are panning out, three quarters of Jet’s capacity will soon operate as Jet Konnect. And therein lies the rub. Expats brought in from across the world for their expertise in shaping a premium service model are now being forced to craft an all-economy airline from the shell of a full service one. Critics of this model, like Kapil Kaul of Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation, say it takes more than selling tickets at low fares to make a successful low cost carrier. To morph into an airline that can pare costs to the bone will be tough with the same managers at the backend.

It is not a game either Goyal or his expatriate managers have played earlier. Until now, the airline has axed jobs, stopped flying on several routes and leased out its brand-new planes. Domestic capacity was reduced by 15 percent in 2008-9, while 23 percent of the international routes got the axe. Foreign cabin crew and ground staff hired at stations like San Francisco and Shanghai were given pink slips. But for the most part, Jet has retained more than a 100 foreign pilots on its roster. All this hasn’t stemmed the bleeding though. In 2008-09, it lost Rs. 1,350 crore. Debt is up to 8.5 times equity. With competition showing no sign of flagging, the next few quarters don’t look any better either.

The losses continue to raise questions on why does the chairman persist with the more expensive foreign talent — particularly when their expertise doesn’t seem to add value in the changed circumstances.

The answer, though, isn’t difficult to figure. If he lets go of them, it will be an admission that his vision of a full service carrier is all but over. No one inside the airline, including his senior managers, believes Goyal is ready to acknowledge that the ground rules in aviation have changed forever. So for the moment, he has an incredible balancing act to perform — at least until the market recovers.

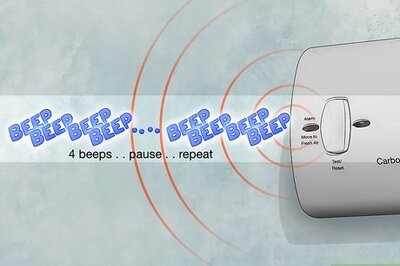

By all accounts, the pressure is mounting. The pilots’ strike is only one sign of things to come. The DGCA (Directorate General of Civil Aviation) has told airlines that foreign pilots will have to be phased out by 2010. Airlines, including Jet, are expected to appeal for an extension, because they believe they need experienced commanders, trainers and examiners.

Over the years, Goyal has managed these dichotomies smartly. He has run Jet Airways with an iron hand. The fact that Jet has never had a strike before is testimony to the maneuvering he is adept at. That is why September’s strike is being seen as evidence that his magic may be fading.

Part of the problem also has to do with the fact that Goyal doesn’t trust his CEO anymore. Wolfgang Prock-Schaeur, an Austrian national, was conspicuously missing from public view during the recent face-off with pilots. Prock-Schaeur had a formidable reputation in managing workforces, built during his earlier stint at Austrian Airways.

The rift between the two of them started when Prock-Scheur took a call to quit Jet and move to arch rival Kingfisher in November 2007. Goyal used his charm to persuade Prock-Schaeur to stay. He did. But things never got back to how they were. Though he continues as CEO, Prock-Schaeur isn’t in the thick of things anymore. He wasn’t part of the decision to reinstate the sacked cabin crew; or to join the group of private Indian carriers in their decision not to fly if the government didn’t cut taxes on aviation fuel.

Last year, Goyal hand-picked Ravi Chaturvedi, who had earned a formidable reputation as president of north-east Asia at Procter & Gamble (P&G), to be his new group CEO. But Chaturvedi put in his papers within three months of joining. Insiders say that he didn’t get along with the chairman on several key issues of culture and decision-making.

For now, that leaves Goyal to wage a largely lonely battle to save his vision of building a world-class airline.

Comments

0 comment