views

The pandemic-induced demand disruption and the resulting loss of jobs in both manufacturing and services have led to a migration of workers from cities to villages. State governments are just becoming aware of this pressure on rural households. Agricultural households have thus far survived because one or more members usually is a salaried worker in the city; with this support missing, agriculture household incomes are further depressed. It is thus important to revamp and revive the functioning of the rural employment schemes. Synergies and efficiencies need to be created and improved to boost rural incomes so that demand can be back at pre-pandemic levels.

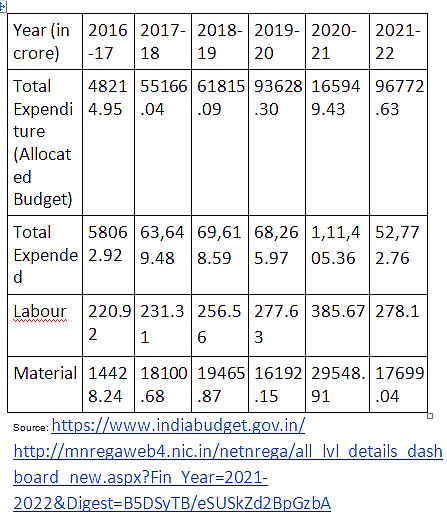

Developing a new scheme takes time. Therefore, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in her stimulus package has increased the allocation of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGS) by 18.69 per cent to Rs 73,000 crore for the fiscal year 2021-22. To a question in Parliament on August 6, 2021, the government said it has already released Rs 46,705 crore to the states and UT and will allot more funds as and when demanded. MNREGS has been in the crossfire of left and right ideologies but has always found political favour. Now that the scheme has been expanded, it is time to look at its ability to nudge capital and consumer spending in rural areas and help individual farmers too.

The utilization efficiency of the scheme has to be increased on the ground. Central government efforts using NREGA software have made it highly efficient. Linkage with Aadhaar and transfer of funds directly into beneficiaries accounts ensure minimum leakage. Therefore, it is time to leverage MNREGS to enhance not only employment but also a better utilization of Rs 73,000 crore.

Unintended Consequences

MNREGS was designed to guarantee 100 days of employment to rural workers. Over the years, it has become a benchmark for minimum rural wage. It has raised rural wages and now there are hardly any areas left where farm labour can be paid less than MNREGS wages. This has benefitted landless agricultural labour but has also increased the cost of production for farmers. Like any other state intervention in market forces, this has had unintended consequences.

Besides MNREGS, there are other schemes at rural level that provide incomes to the rural poor. All these welfare schemes have contributed to wage inflation for agricultural labour needed for sowing, harvesting or other agricultural activities. States like Haryana, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and even Western UP depend upon migrant population for harvesting. In the last 18 months, migrant labour has not been keen on moving; as a result, harvesting in these states has suffered and is depending more and more on mechanization.

ALSO READ | Turned Away from Jobs in Cities, MGNREGS Beneficiaries Crossed 11cr Mark For First Time During Pandemic Year

Mechanized harvesting creates its own challenges of leaving residue in the farm, especially rice and wheat, which due to lack of labour cannot be cleared and is burnt. This massive burning across fields leads to pollution in cities of the North and is suffered by the region’s city dwellers. An unintended consequence of higher rural wages and higher mechanization is pollution. Mechanized harvesting is also not possible for very small farms; large combine harvesters cannot turn or move around in small farms. In the case of sugarcane, the harvester cuts green stalks along with the cane leading to increase in weight for the mill but a lower yield of sugar per kg, distorting the price dynamics. Again the sugarcane harvester cannot work in very small farms.

There is a way to resolve this issue by involving individual farmers to use MNREGS labour for harvesting or post-harvesting activities. Small farmers could pay, say 25 per cent, of the labour wages and the remaining 75 per cent could come from MNREGS. This would ensure productive use of MNREGS labour and bring down the cost to the farmer, thus increasing his income. This would go a long way in helping the government achieve its stated goal to double farmers’ incomes.

Capacity for Projects

My organization, the Center for Innovation in Public Policy (CIPP), has, since its inception, been working in the Nuh district of Haryana with the long-term objective of setting up a rural lab with local people to study and report the implementation of policies on the ground. We have been studying several MNREGS on the ground and documenting their development. Nuh is an aspirational district and as a backward district is expected to get a higher allocation of MNREGS fund among the other 22 districts of Haryana. But the challenge of a backward district is exacerbated with the lack of capacity and capability on the ground.

We have observed that it is almost impossible for junior engineers (JEs) from the panchayat department to conceptualize large projects like affordable housing. The JE plays an important role in every MNREGS project as he/she has to build the costing for the project. A sarpanch in a village also does not have the skills to conceptualize an affordable housing project. A housing project is a construction project requiring skilled labour and material; the simple format of the NREGS software has to be adapted for it. The software assigns work codes to every part of the project if it is too big. The payment for labour and material is made through this software. Job cards are uploaded for the labour and bills for material are processed and transferred directly by the central government.

In a construction project, the panchayat will have to engage an architect to design the project on the ground studying the lay of the land. But MNREGS software does not have the flexibility of paying a highly skilled person as an architect. Even a skilled mistri (bricklayer) or a supervisor cannot be hired. The quick answer to this problem would be to use the resources under PMAY-Gramin for material and design and MNREGS for labour. This has been envisaged but it does not happen as the Sarpanch or the JE, or even the ABPO (Additional Block Programme Officer), do not have the capability, skills, or authority to combine different schemes. Collaboration between two different departments of the government is rarely seen at the top due to structural issues and is almost impossible on the ground.

There is no incentive for village or block-level officers to collaborate and because of turf issues, proposals for joint projects are seen as ‘meddling’. It is only if the DC has the vision will such projects get conceptualized and executed. It is too much to ask from a District Commissioner (DC) as the number or departments are the same as under a Chief Minister but without the corresponding support staff.

The solution for conceptualizing projects also lies in the NREGS software, which can have modules for adapting models for constructing projects. Whether they are for affordable housing in the rural areas or check dams and water harvesting projects under Jal Shakti Mission. This would help in raising the capability of the engineering staff and the panchayats to create better and bigger projects.

Technology has to be used to bridge this gap, maybe it is time to create an open source digital stack as a public digital infrastructure for designing projects on the ground. A lego-like design tool that helps in estimating material and labour requirements and assigns their payment to various schemes. That pays the labour component from MNREGS and material component from PMAY-Gramin scheme. This is an innovation that would go a long way towards better utilization of the government spending on the ground.

K. Yatish Rajawat is a policy analyst at Center for Innovation in Public Policy. He tweets @yatishrajawat. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Assembly Elections Live Updates here.

Comments

0 comment