views

It’s a ritual now. As Delhi’s air quality slips into poor and severe categories in October/November, finger-pointing and blame game starts. Then knee-jerk reactions like spraying water on roads, odd-even rules for vehicles, smog tower, etc., follow to show that something is being done to reduce pollution. The judiciary doesn’t want to be left behind, so suo motu directions are issued by the National Green Tribunal (NGT), High Court and the Supreme Court. These reactions continue till March, and then things are back to normal, to start again in October/November.

So, the question is: Why are we not able to reduce pollution in Delhi? Where are we going wrong?

Let’s be clear, despite the claims made by the Delhi government, the pollution in the city has worsened over the years. As per the National Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Programme of the Central Pollution Control Board (CBCP), the PM2.5 level has increased from 63 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3) in 2012 to 141 µg/m3 in 2019. This dipped to 115 µg/m3 in 2020 due to COVID lockdowns, but the PM2.5 level was still nearly three times the national standards. This is when the city has taken the most actions to reduce pollution.

Delhi has shifted highly polluting industries to the outskirts, moved its public transport to CNG, closed power plants, imposed strict emissions norms on vehicles, restricted entry of heavy vehicles, restricted gensets, and distributed LPG cylinders. And yet, Delhi’s PM2.5 level has more than doubled in the last decade. The obvious question is why?

To answer this, we have to understand the nature of the problem and evaluate whether the solutions being implemented are appropriate or not.

First, it is important to understand that Delhi’s geographical area is just 2.7 per cent of the National Capital Region (NCR). So, Delhi’s air pollution is not just due to its own sources; it gets polluted from the NCR districts, including from the larger Indo-Gangetic airshed. Though there are different estimates on how much pollution is coming from outside (some estimates suggest as much as 60 per cent), it is well established that Delhi’s air quality cannot be improved significantly without controlling pollution in Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan.

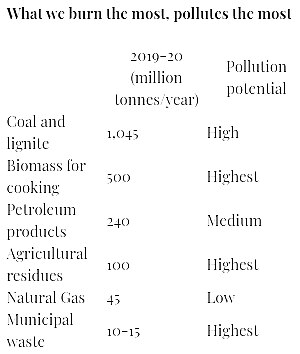

Second, pollution is directly related to what we burn. In 2019, the country burned 1,830 million tonnes (MT) of fossil fuels and biomass to meet its energy needs. In addition, about 100 MT of agriculture residues and 10-15 MT of garbage were burned in the open. In total, we burned at least 1,950 MT of materials, of which 85 per cent was coal and biomass, and petroleum products were less than 15 per cent.

If we only consider the number of materials we burn, then at an all-India level, at least 85 per cent of air pollution is generated from coal, biomass, and garbage; petroleum products and gas contribute less than 15 per cent. But, as coal and biomass are the most polluting fuels, their contribution is likely to be even higher.

Third, the dust has emerged as a significant source of particulate matter (PM) pollution. For example, studies indicate that as much as 20-30 per cent of PM2.5 in Delhi can be attributed to dust generated from construction sites and roadsides and wind-blown dust from degraded lands in neighbouring states. In fact, land degradation and desertification are now major sources of dust pollution across the country, as around 30 per cent of the country’s land is either degraded or facing desertification, and 26 states have recorded an increasing rate of desertification in the past decade.

What emerges from the above is that if we want to reduce air pollution in Delhi, our focus has to be on reducing coal and biomass burning and tackling land degradation and desertification in Delhi-NCR, and in neighbouring states. Unfortunately, in the last 20 years, we have done the opposite. The entire focus of our air pollution mitigation has been the automobile sector, where most petroleum products are consumed. In contrast, power plants, industries, biomass burning, and land management have received inadequate attention. This is precisely why Delhi’s and the country’s air pollution levels are increasing and not decreasing.

Regrettably, even today the action plan of the Delhi government and, for that matter, across the country is too focused on the automobile sector and thus is only addressing 15 per cent of the pollution problems. The remaining 85 per cent — biomass, coal, and land management — are complex problems and require fundamental changes in energy and land management policy and practices. These cannot be solved in one election cycle and require tough decisions that most politicians will avoid. After all, it is easier to put up a smog tower and show your voters that you are doing something for air pollution than to ask poor households to stop cooking on biomass.

But if we want to reduce air pollution significantly, then there is no easy way out. We will have to work with millions of households to eliminate biomass as cooking fuel, with millions of farmers to restore land and stop stubble burning, and with hundreds of thousands of industries to reduce pollution from coal (and ultimately eliminate coal).

The bottom line is that no country in the world has managed to reduce air pollution by burning massive proportions of solid fuels — coal and biomass. Coal and biomass are not a big part of the energy mix in Europe or the US. China reduced its air pollution by reducing coal consumption in power plants and industries and shifting millions of households to clean cooking fuels. We are no different and will have to significantly reduce and control pollution from coal and biomass. So, if any politician is selling the dream that we can control air pollution in a few years, then don’t buy that dream. We will have to go through a difficult transition period of at least a decade before we can breathe clean air.

The writer is one of India’s foremost environmental and climate change experts. He is the President & CEO of the International Forum for Environment, Sustainability and Technology (iFOREST). He was Deputy Director of the Centre for Science and Environment during 2010-19. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment