views

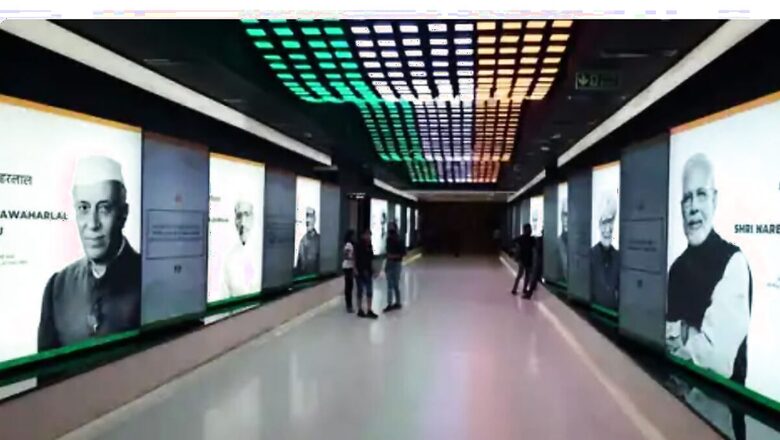

The change in name of Nehru Memorial and Museum Library (NMML) to Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library has brought a strong reaction from the Congress party. This reaction is largely an outcome of that sense of entitlement which the Congress has been carrying since Jawaharlal Nehru became the first Prime Minister of the independent India.

There have been fourteen Prime Ministers and everyone tried to do their bit for the country. Their legacy needs to be showcased too and what better way to do it than to set up a museum where one can go and have a look at their lives and actions. And then we can leave the rest to the people of the country. They can judge themselves who was the best Prime Minister for the country?

The controversy that erupted after renaming of the NMML however also brings to the fore another interesting question: Was Nehru the best Prime Minister for the country? Could he do no wrong?

There are certain chapters of history that we need to revisit to find an answer to these questions. These chapters have been carefully hidden by successive Congress governments with the aid of Leftist intellectuals. A manicured image of Nehru as a true democrat and the most popular leader and visionary has been nurtured. Anyone who raises any uneasy questions about Nehru is conveniently dubbed as a right-wing communalist who wants to rewrite the wrong history. Ironically, the situation is quite the opposite.

Some of the well-known facts about Nehru’s era is that India lost to China in a disastrous war in 1962 purely because we were ill-prepared. We gave away Tibet on a platter to China. The way Kashmir was handled opened a Pandora’s box for India. Article 370 was imposed which became the root cause of the Kashmir problem for the next several decades. Inflation had skyrocketed, industrial growth was poor, the farm sector was laggard, unemployment was rampant and millions of Indians remained impoverished during the Nehru era. There are some other aspects of the Nehru era also that are least known. So let us take a brief look at them.

Nehru and Corruption

Walter Crocker, an Australian diplomat who spent around 10 years in India during Nehru’s regime as the Australian High Commissioner, has given a detailed account of misgovernance and corruption in Nehru: A Contemporary’s Estimate. This widely-acclaimed first-hand account was first published in 1966. Crocker observed, “In Punjab, the state which adjoins Delhi, a regime flourished for as long as eight years (1956-64), the last eight years of Nehru’s life which was vitiated with corruption and abuse of power… Nehru, apparently convinced that the Chief Minister (Pratap Singh Kairon) was indispensable for maintaining political stability in the state… resisted demands for an inquiry.”

Kairon had to resign but only after Nehru’s death as Justice SR Das Committee indicted him. This report was released three weeks after Nehru’s death.

Crocker also talked about corruption in other Congress ruled states during the Nehru era. “In another state adjoining Delhi, important persons in its government and in the local Congress party were involved in large scale smuggling across the Pakistan-Rajasthan border. The Bakshi regime in Kashmir was another example of misuse of office and it lasted longest of all. There were some other states with Congress governments which also carried corruption far. And there were some ministers in Nehru’s cabinet who could not have survived a proper investigation…This is to say Nehru found himself with a degree of power which has rarely been precedent, yet in practice he made relatively little use of it. Why?”

Veteran journalist Durga Das gave a first-hand account of the Nehru era in India from Curzon to Nehru and After. Das explained how Congress was turned into a personal fiefdom by Nehru: “There was a great rush for Congress tickets (for first general elections of 1952) because of the general feeling that ‘even a lamp post carrying the Congress tickets will win’. As was natural, many candidates made allegations of corruption, immorality and black marketing against their rivals. A committee was appointed to screen the applications and its slogan was: Let us give Nehru the 500 men he wants and five years — and leave the rest to him.’ Gandhi’s wishes that deserving men from various professions and spheres of activity be inducted into public life was quietly forgotten.”

Das observed that the Congress won the general election, and gave birth to a new phase in India’s political life, namely the emergence of top courtiers, sycophants and hangers-on.

Das also explains a chain of events in the run-up to the first general elections that raises a big question mark on Nehru’s propriety. “Nehru did not think it proper to travel for his election campaign in the aeroplane he used for official purposes as prime minister. At the same time, neither he, nor the Congress party could afford to charter a plane for the purpose. An obliging Auditor-General salved Nehru’s conscience by devising a convenient formula. The prime minister’s life, he said, must be secured against all risks, and this could be assured best, if he travelled by air. Air transport would avoid the need for large security staff required if he travelled by the rail. Since it was the nation’s responsibility to see to his security, the nation must pay for it.”

“So, a rule was framed that Nehru would pay the government only the normal fare chargeable by civil airlines for transporting a passenger. The fares of the security staff accompanying him would be paid from government funds, and any Congressman accompanying Nehru would pay his own way. Thus, by contributing a bare fraction of the total expenses, Nehru was able to acquire a mobility which multiplied a hundredfold his effectiveness as a campaigner and vote-catcher. As Prime Minister, Nehru received top priority in all communication media, particularly the press and the government-controlled radio. Day after day Nehru’s pictures and speeches would crowd out anything said by his rivals and the opposing political parties.”

Nehru as a Democrat

Those who have been flaunting Nehru as a true democrat may revisit the way polls were held for the post of Congress president in 1950 and the subsequent developments.

Nehru opposed Purushottam Das Tandon’s candidature tooth and nail and even threatened to resign from the government if Tandon was elected. But Tandon was able to defeat Nehru’s candidate Acharya JB Kripalani quite convincingly. It also shows that Nehru wasn’t as popular in his own party as it has been projected.

But Nehru did not rest his case as a true democrat should have. He went after Tandon.

S Gopal describes in Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, “He (Nehru) agreed to serve on the working committee but made known his disapproval of the selection of many other members by Tandon, and claimed the right to raise basic issues at the first meeting of the new committee. He could only continue as a member if he felt that the situation in the Congress would be grasped in the way he wanted and a new turn given to the organisation.”

In August 1951, Nehru triggered a major crisis by resigning from the Congress Working Committee. This was followed by a meeting of the Congress Parliamentary Party. All the CWC members were compelled to resign. This made Tandon’s position untenable. The first general elections were a few months away. Unlike Nehru who was not bothered about the damage being caused to the Congress Party due to his tantrums, Tandon, as a true Congressman, was concerned about the impact of all these developments on Congress’ electoral fortunes in forthcoming polls. Thus, to salvage the party’s image, Tandon resigned in September 1951. This is what Nehru had always wanted. Now, Nehru took over as Congress president. And since then, the Congress party has been run as a family fiefdom.

Conclusion

Indian polity has developed a fundamental flaw over the last seven and a half decades. When it comes to our public figures especially from the past, either we treat them as ‘Gods’ or as ‘Devils’. Probably, it is better to assess them as human beings who did some good work and committed mistakes too. So, while we appreciate their good work, we also need to critically assess their mistakes so that the present and the future leadership can learn from these mistakes. Nehru also falls in the same category. He did some good work for the country and committed several mistakes also. And going by his track record, he certainly isn’t first among the equals.

The writer, an author and columnist has written several books. He tweets @ArunAnandLive. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Comments

0 comment