views

Parveen Shaikh was ecstatic when she learned that she was going to be relocated to Govandi, a suburban neighbourhood in eastern Mumbai, known for the over 120-hectare Deonar dumping ground in its backyard.

The 42-year-old grassroots activist had spent her entire life in shanties on the footpaths of Sewri until finally in 2008, luck smiled upon her. After years of perseverance, she was rehabilitated by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) to a Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) colony in Govandi’s Shivaji Nagar under the Mahatma Gandhi Path Kranti Yojana. “For some time, it felt like all our dreams were fulfilled,” she says. It was only after a few weeks that she realized that the new house came with its own set of issues. “Ghar toh mil gaya, lekin isme rehna toh mushkil tha (we got the house but living in it was going to be tough),” she recalls.

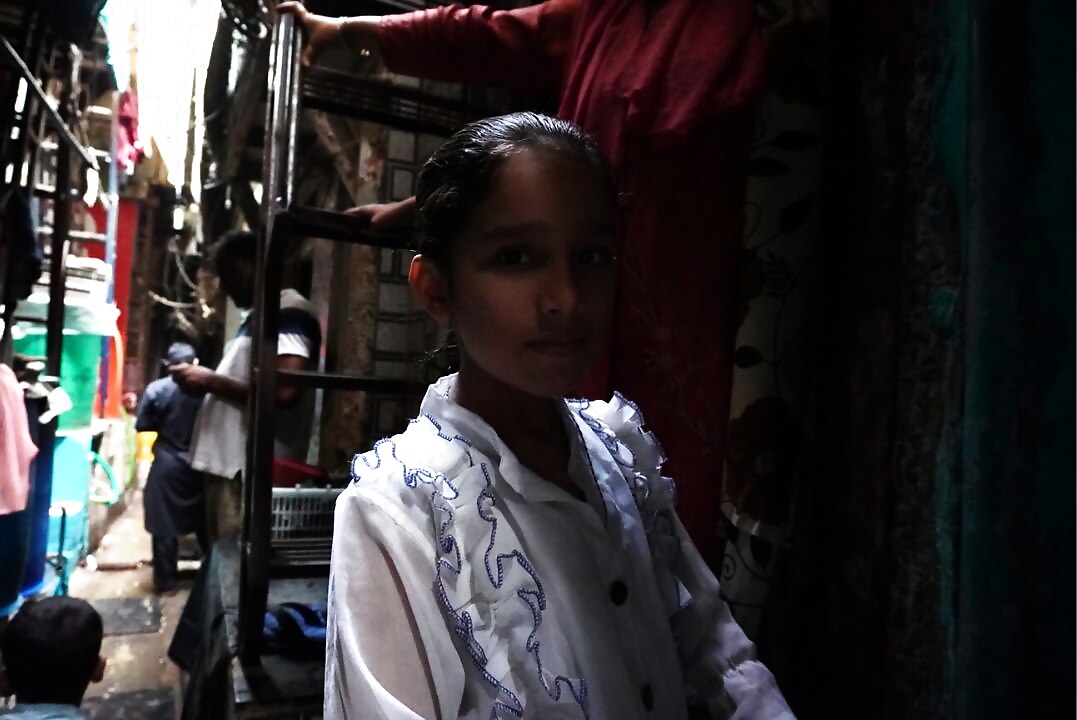

Shaikh isn’t the only one. Govandi is part of Mumbai’s M-East ward, one of the city’s poorest and most ignored areas where residents are engaged in a daily battle against a host of issues, including respiratory diseases, malnutrition, sanitation, education and drug abuse.

What is remarkable, however, is the constant drive among residents to change things. Residents become local activists and advocates, pushing for improvement across the board.

‘RESIDENTS HERE MAY NOT LIVE PAST 39’

A 2009 study stated that the average life expectancy in Govandi is 39 years, nearly half the national average. Recording a slum population of over 70 per cent, the M-east ward ranked lowest in the Mumbai Human Development Report, 2009. A 2018 study by the NGO Apnalaya stated that 145 residents shared one community toilet seat in Shivaji Nagar.

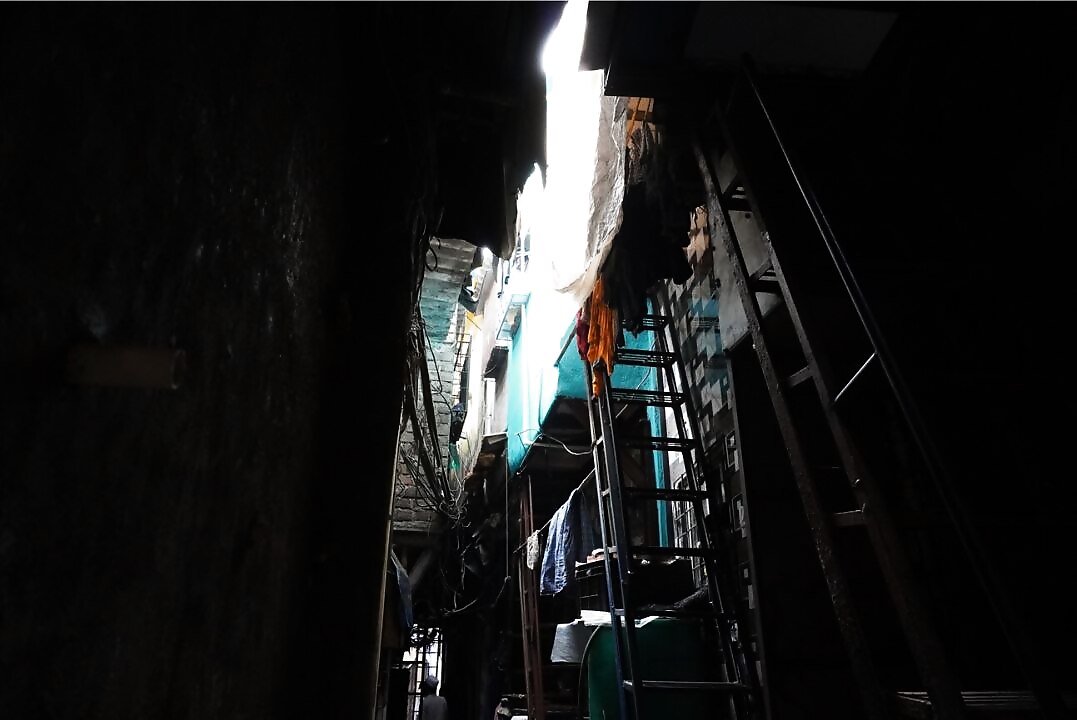

Shivaji Nagar and its peripheral colonies – clusters of informal settlements that have popped up near the locality – ring the massive Deonar dumping ground which was established nearly 123 years ago and where much of the city’s garbage goes. The dumping ground contributes to several issues that residents face. Additionally, a biomedical waste plant in the vicinity since 2009 has added to the concerns.

“The creation of M-east ward as a site for all informal settlements and resettlement colonies is not accidental,” Ishita Chatterjee, a researcher working on informal urbanism, tells News18. “The location of hazardous industries, the dumping yard, even that is not accidental,” she says.

“M-east ward has been the dumping site of unwanted land uses…so bastis end up being considered unwanted, they are dumped here…” says Chatterjee. A majority of the population in the M-east ward is made up of Muslims, Dalits and OBCs. The residents are migrants who move here for the cheap living options and those, like Parveen Shaikh, who are resettled here.

BASIC ISSUES OF SURVIVAL…AND THEN SOME

The issues plaguing Govandi are layered, and they often run into one another. Bhawna Jaimini, an urban practitioner working in Shivaji Nagar with the Community Design Agency, tells News18, “There are really basic issues of survival…the key issues are the infrastructure, the [poor] air quality, the lack of basic services such as water…once those get solved we can think about issues like affordable education, etc.”

Nafees Ansari, a liason consultant and a resident of Lotus Colony in Shivaji Nagar, is on a similar trajectory. He works as an RTI activist and has been helping Alam build a case to get the bio-medical waste plant moved. However, another issue he is concerned about is the rampant drug abuse. He has found it challenging to access any data on the issue through RTIs. Once this is sorted out, the next issue will be drug abuse and drug peddling…we’ll fight it out, he says.

AN ENGINEER FIGHTS A LEGAL BATTLE

26-year-old Shaikh Faiyaz Alam has been fighting relentlessly to move the bio-medical waste plant. Born and raised in Kamla Raman Nagar, a settlement close to Shivaji Nagar, he resides a stone’s throw away from the SMS Envoclean plant. Fumes from the plant’s incinerator have often left a layer of black soot on cars and objects in the area, he says.

In 2021, he set up an NGO, the Govandi New Sangam Welfare Society, and has been taking the case forward in the Bombay High Court. Alam graduated as an engineer and now runs a taxi business. His office doubles up as a meeting point for local activists who work with him and his organization. Figuring out the right channels to file RTIs and PILs was complicated for him at first, he says, but he picks it up as he goes. He is also now pursuing an education in law to carry on the advocacy.

Alam also established a Twitter page in 2021 – a forum for all and any civic issues plaguing the community. Called “Govandi Citizens #”, the Twitter page shares and amplifies local civic issues, tagging relevant authorities and often getting swift responses.

Walking through the alleys of Kamla Raman Nagar with a swagger of one who has studied his neighbourhood to the T, he says, “I am a resident of this place and I know the people, their issues very closely. Whatever skills, knowledge I have, I’m using it for [my] people”.

‘FOR THE KIDS’

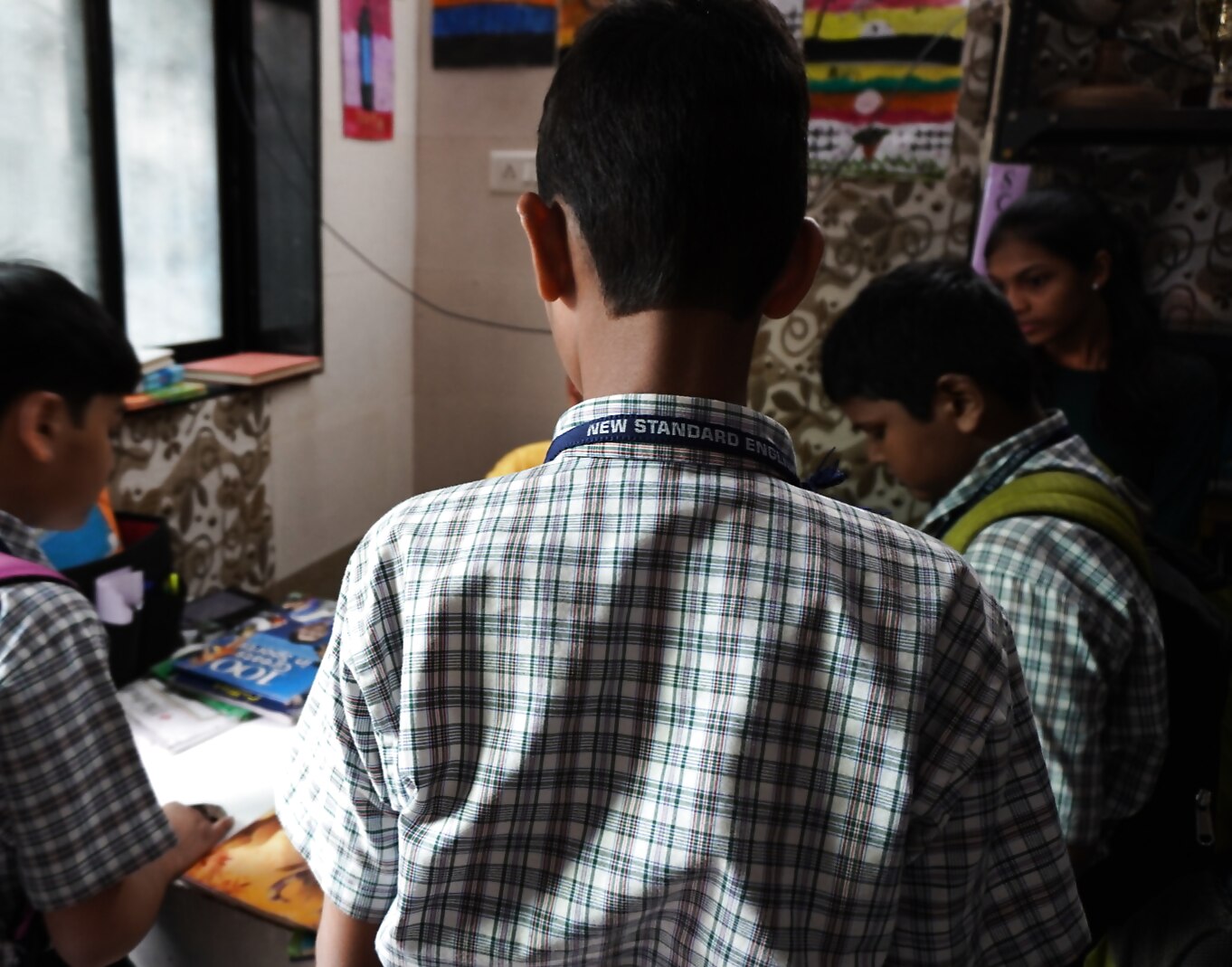

Even as some residents push to solve these fundamental issues, in other parts of the neighbourhood, cultural movements blossom. In a shaded alley in a corner of Shivaji Corner, Anoop Parik, a former Teach for India teacher runs the Next Page Centre community library. A sleepy space while school is on, the library is thronged by school children clamouring for a new book, as soon as the bell rings.

Parik also runs a football community program, and both the football program and the library are manned by local teens and twenty-somethings. Shweta Shetty, 20, works as a football coach and at the library. “Some of us were [privileged] to have TFI teachers…and we were taught in a different way than others here, for example we can communicate much better,” she says.

For her, coaching and teaching is a way to pass on her learnings. “I think the change comes from within us…instead of waiting for others, we’d rather do it ourselves,” she says. “It might be a very small contribution to the society, but kids really gain so much.”

The youth in Govandi understand the difference between their neighbourhood and others, Parik says. “They recognize the need for change.”

“They’re hungry,” says Jaimini. “They’re hungry for opportunities, for action, for doing things.” Parents and youth News18 spoke to say that Govandi is “blacklisted” and they are often discriminated against when applying for jobs, etc because of their neighbourhood.

Parveen Shaikh, who was relieved that her two sons would have a valid address proof after being resettled to Govandi, says that the residents and youth want to change the area’s negative image. “We may not have studied a lot, but it had always been our dream that our children study, graduate, get the right opportunities.”

Today Assistant Commissioner of @mybmcWardME Mr.Mahendra Ubale called @newsangam1's most active members @skfaiyaz43 & @NafeesA86509361 for discussion on the issue of Bio- Medical Incinerator and Structural Audit of GMLR bridge.cc: @IqbalSinghChah2 @mybmc pic.twitter.com/cBb9Tmv47o

— Govandi Citizens # (@GovandiCell) December 23, 2022

Shaikh and Jaimini both work with the Community Design Agency and are setting up the Govandi Arts Festival, which will be held in February 2023. A group of 45 youths from the MMRDA colony are being trained in photography, public art, rap and more and will showcase it at the festival.

“People always tell the kids of Govandi to become plumbers, electricians…girls are advised to become beauticians, etc…why can’t our children be photographers or public artists or filmmakers,” Shaikh asks.

Jaimini points out that there is a key ingredient apart from the basics. “I think what really makes a neighborhood livable is people…when people work together, live together, when there is respect, there is a sense of collaboration, cooperation and collectiveness within people.”

Read all the Latest India News here

Comments

0 comment