views

Researching the Topic

Choose a subject that interests you if the topic isn’t assigned. Speech topics are often assigned but, if you need to pick your own, write a list of subjects that interest you. Choose a subject that you know a lot about or that you’d be eager to research. Then narrow your focus on a specific topic, and make sure it meets the requirements listed in the prompt. Suppose your prompt instructs you to inform the audience about a hobby or activity. Make a list of your clubs, sports, and other activities, and choose the one that interests you most. Then zoom in on one particular aspect or process to focus on in your speech. For instance, if you like tennis, you can’t discuss every aspect of the sport in a single speech. Instead, you could focus on a specific technique, like serving the ball.

Gather a variety of reliable sources to back your claims. While you may reference your personal experience in the speech, you’ll need to conduct research and cite authoritative sources. The right sources depend on your topic, but generally include textbooks and encyclopedias, scholarly articles, reputable news bureaus, and government documents. For example, if your speech is about a historical event, find primary sources, like letters or newspaper articles published at the time of the event. Additionally, include secondary sources, such as scholarly articles written by experts on the event. If you’re informing the audience about a medical condition, find information in medical encyclopedias, scientific journals, and government health websites.Tip: Organize your sources in a works cited page. Even if the assignment doesn’t require a works cited page, it’ll help you keep track of your sources.

Form a clear understanding of the process or concept you’re describing. Make sure you know your topic inside and out; you should be able to describe it clearly and concisely. In addition to conducting research, talking to your family and friends about your topic can help refine your understanding. For instance, if your speech is on growing plants from seeds, explain the process step-by-step to a friend or relative. Ask them if any parts in your explanation seemed muddy or vague. Break down the material into simple terms, especially if you’re addressing a non-expert audience. Think about how you’d describe the topic to a grandparent or younger sibling. If you can’t avoid using jargon, be sure to define technical words in clear, simple terms.

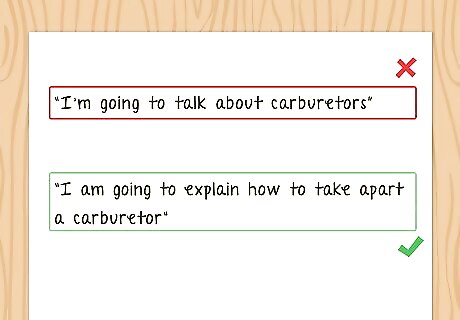

Come up with a thesis that concisely presents your speech’s purpose. Your thesis conveys your speech’s central focus and should be as specific as possible. Check with your instructor about formatting your thesis. They may encourage you to describe your purpose by referencing yourself. However, if your assignment calls for more formal language, you’ll need to skip phrases such as “My purpose is” or “I’m here to explain.” For example, if your speech is on the poet Charles Baudelaire, a strong thesis would be, “I am here to explain how city life and exotic travel shaped the key poetic themes of Charles Baudelaire’s work.” While the goal of an informative speech isn't to make a defensible claim, your thesis still needs to be specific. For instance, “I’m going to talk about carburetors” is vague. “My purpose today is to explain how to take apart a variable choke carburetor” is more specific.

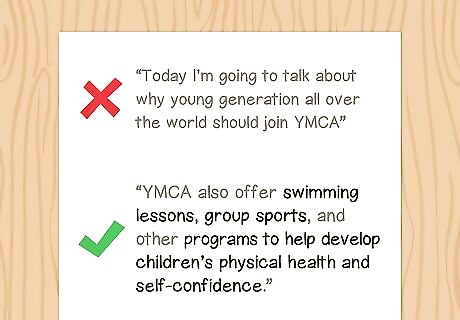

Focus on informing your audience instead of persuading them. Keep in mind an informative speech doesn’t aim to persuade the audience to accept a claim. Instead of crafting an argument or appealing to emotions, present an objective speech that clearly spells out your subject matter. This means your organization and language need to be step-by-step instead of argumentative. For instance, a speech meant to persuade an audience to support a political stance would most likely include examples of pathos, or persuasive devices that appeal to the audience's emotions. On the other hand, an informative speech on how to grow pitcher plants would present clear, objective steps. It wouldn't try to argue that growing pitcher plants is great or persuade listeners to grow pitcher plants.

Drafting Your Speech

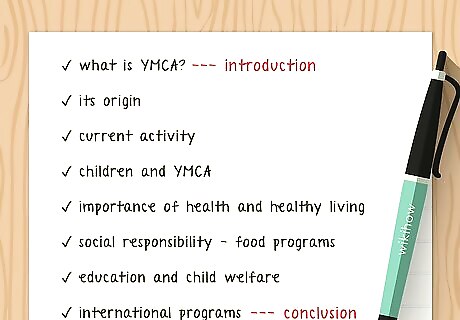

Write a bare bones speaking outline for delivering your speech. After you’ve written a complete sentence outline, whittle it down to a skeleton outline. A skeleton outline includes short words and sentence fragments instead of full sentences. You can write the speaking outline on notecards and use them to stay on track when you deliver your speech. Delivering memorized remarks instead of reading verbatim is more engaging. A section of a speaking outline would look like this:III. YMCA’s Focus on Healthy Living A. Commitment to overall health: both body and mind B. Programs that support commitment 1. Annual Kid’s Day 2. Fitness facilities 3. Classes and group activities

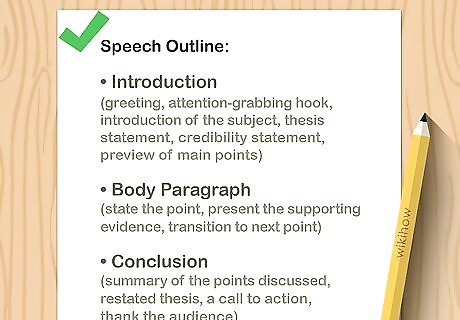

Include a hook, thesis, and road map of your speech in the introduction. It's common to begin a speech with an attention-grabbing device, such as an anecdote, rhetorical question, or quote. After getting the audience's attention, state your thesis, then preview the points your speech will cover. For example, you could begin with, “Have you ever wondered how a figure skater could possibly jump, twist, and land on the thin blade of an ice skate? From proper technique to the physical forces at play, I’ll explain how world-class skaters achieve jaw-dropping jumps and spins.” Once you've established your purpose, preview your speech: “After describing the basic technical aspects of jumping, I’ll discuss the physics behind jumps and spins. Finally, I’ll explain the 6 types of jumps and clarify why some are more difficult than others.” Some people prefer to write the speech's body before the introduction. For others, writing the intro first helps them figure out how to organize the rest of the speech.

Present your main ideas in a logically organized body. If you’re informing the audience about a process, lay out the steps in the order that they need to be completed. Otherwise, organize your ideas clearly and logically, such as in order of importance or in causal order (cause and effect). For instance, if your speech is about the causes of World War I, start by discussing nationalism in the years prior to the war. Next, describe the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, then explain how alliances pulled the major players into open warfare. Transition smoothly between ideas so your audience can follow your speech. For example, write, “Now that we’ve covered how nationalism set the stage for international conflict, we can examine the event that directly led to the outbreak of World War I: the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Review your main points in the conclusion. Think of a speech’s order as “Tell them what you’re going to tell them, tell them, then tell them what you told them.” Summarize your thesis and main ideas in the conclusion, but don’t repeat them word-for-word. Additionally, to connect with your audience and demonstrate your topic’s importance, try to relate the subject matter to their lives. For instance, your conclusion could point out, “Examining the factors that set the stage for World War I shows how intense nationalism fueled the conflict. A century after the Great War, the struggle between nationalism and globalism continues to define international politics in the twenty-first century.”

Write a complete draft to edit and memorize your speech. Your complete sentence draft is like a research paper; it should include every sentence in your speech. It’s basically the script you’ll use to organize your introduction, body, and conclusion, make revisions, and memorize your presentation. Typically, speeches aren’t read verbatim. Instead, you’ll memorize the speech and use a bare bones outline to stay on track.Avoid information overload: When you compose your speech, read out loud as you write. Focus on keeping your sentence structures simple and clear. Your audience will have a hard time following along if your language is too complicated.

Perfecting Your Delivery

Write the main points and helpful cues on notecards. Memorizing the introduction, key points, and conclusion word-for-word is wise. However, unless your teacher requires it, don’t feel like you have to memorize the entire speech verbatim. Reciting a completely memorized speech can feel stiff, so just commit the content to memory well enough that you can explain your ideas clearly and consistently. While it’s generally okay to use slightly different phrasing, try to stick to your complete outline as best you can. If you veer off too much or insert too many additional words, you could end up exceeding your time limit. Keep in mind your speaking outline will help you stay focused. As for quotes and statistics, feel free to write them on your notecards for quick reference.Memorization tip: Break up the speech into smaller parts, and memorize it section by section. Memorize 1 sentence then, when you feel confident, add the next. Continue practicing with gradually longer passages until you know the speech like the back of your hand.

Project confidence with eye contact, gestures, and good posture. Use hand gestures to emphasize key words and ideas, and make natural eye contact to engage the audience. Be sure to switch your gaze every 5 or 10 seconds instead of staring blankly in a single direction. Instead of slouching, stand up tall with your shoulders back. In addition to projecting confidence, good posture will help you breathe deeply to support your voice.

Practice the speech in a mirror or to a friend. Once you’ve committed the speech to memory, work on making your delivery as engaging as possible. Watch yourself in a mirror or record yourself to make sure you appear confident and natural. Get a second opinion and ask a friend or relative to watch you and offer feedback. Have them point out any spots that dragged or seemed disorganized. Ask if your tone was engaging, if you used body language effectively, and if your volume, pitch, and pacing need any tweaks.

Make sure you stay within the time limit. Use a stopwatch or cell phone app to time yourself when you practice your speech. Speak clearly and avoid rushing, but work on keeping your speech under the time limit, if your instructor set one. If you keep exceeding the time limit, review your complete sentence outline. Cut any fluff and simplify complicated phrases. If your speech isn’t long enough, look for areas that could use more detail or consider adding another section to the body. Just make sure any content you add is relevant. For instance, if your speech on nationalism and World War I is 2 minutes too short, you could add a section about how nationalism manifested in specific countries, including Britain, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Serbia.

Comments

0 comment