views

Developing Your Story

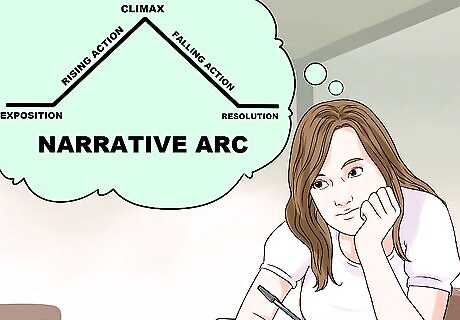

Learn the basic structure of a narrative. Before you can write your epistolary narrative, you need a story to tell. You must develop a “narrative arc” before you start thinking about writing the letters in your story. In the simplest terms, a narrative arc should transition from exposition to rising action to resolution. If you mapped the tension of a story on a line graph, it would rise gradually, then climax at a sharp peak, then drop back down as the situation resolves.

Provide background information in the exposition. As your story begins, you need to establish three things: main characters, setting, and mood. Once your reader understands these three elements of your story, they will be able to follow the twists and turns of the plot when it gets more complicated. Characters: Who is the main character, and who are the most important secondary characters? Is there an antagonist? Who is writing the letters and who is receiving them? Setting: Where and when does this story take place? Paint a clear picture for the reader. “When” a story takes place might even refer to where the protagonist is in his or her life. For example — is your main character an adult reading old diary entries from childhood? A child writing letters to her future self? Mood: The reader wants to know what kind of story they’re reading. Comedies should be light-hearted from the beginning. If your main character is a tortured hero, you should hint at the angst from the beginning.

Present the protagonist with conflict during the rising action. If your story doesn't have conflict in it, your readers won't care enough to keep reading. Conflict falls into three categories: internal, external, and situational. Most good stories will have a combination, if not all, of them. Internal conflict is the protagonist's struggle with himself: regretting past mistakes, struggling with insecurities, grappling with important decisions. Judy Bloom's books are excellent explorations of internal conflict. External conflict is the protagonist's struggle with an antagonist, whether another person (Edmund in Shakespeare's King Lear ) or an entire societal system (George Orwell's 1984). Situational conflict arises from circumstances that get in the protagonist's way. For example: your protagonist is rushing home to apologize to his mother before she dies. But he gets locked out of his apartment without his luggage, and then the taxi gets stuck in traffic. When he gets to the airport, the flight is delayed.

Bring the conflict to a head at the climax. This should occur close to the end of your story, after the tension from all your conflicts has built up over time. When your readers are on the edge of their seats, have your protagonist face his central, most important conflict head on. Ideally, he will face both internal and external conflict in the moment. For example, say your protagonist confronts the school bully in your climax. The bully is the external conflict. But the main character’s insecurity and lack of confidence in the internal conflict. He will have to face both obstacles in the climax.

Release the tension in the resolution. After the climax, give the readers “falling action.” This is a gentle return from the tensest moment in the story to a place where the reader imagines the character will spend the rest of his life. Note that this doesn’t always have to be a happy ending, though. In a happy or comic ending, the main character ends up happier than he’s ever been before. Most children’s stories have happy endings — Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, for example. In a tragic resolution, though, the main character might lose everything. Hamlet, for example, overcomes his obstacles only to die at the end of Shakespeare’s play.

Include a denouement. Some stories include a section in the falling action that ties up loose ends. This is especially common in mysteries or thrillers, in which the person who solved the mystery might explain how they did so. Even if you’re writing a different kind of story, you may need to explain how things resolved before giving the reader your final ending. For example, if your protagonist dies in the climactic scene, what happens to his children? How do the relationships around him go forward?

Outlining Your Approach to the Letters

Decide how much of the story will be told through letters. There's no single formula to writing an epistolary narrative. Some novels, like Bram Stoker's Dracula, are written entirely as letters. Others, like Orson Scott Card's Ender's Shadow Saga, start chapters with letters, then go back to traditional narration. But whether you want a ten-page story or a 250-page novel, don't feel pressured to tell the whole story through letters. Especially if you are just starting out as a writer, it will be easier to combine the letters with traditional narration. Decide how much of the story you want to tell through letters.

Figure out who will be speaking in the letters. You can limit the point of view to a single character, as Stephen Chbosky does in The Perks of Being a Wallflower. In this novel, all of the letters are written by the protagonist (main character), a teenaged boy named Charlie. You can also choose to present multiple voices through the letters, as Stoker does in Dracula. Each of the main characters in this novel gets their own chapters to speak — Jonathan Harker, Mina Murray, Dr. Seward, and Lucy Westenra.

Determine whom the letters will be addressed to. Again, there is no single strategy for writing these letters. In Helen Fielding's Bridget Jones's Diary, all the letters take the form of diary entries. Dracula mixes diary entries with letters written between characters and newspaper clippings. If you are new to the form, you may find it easier to choose a single recipient for all the letters. This will allow you to really develop the relationship — whether the letters are written to a person or as diary entries to oneself. If you're feeling adventurous, though, you can play with a combination of different recipients.

Use the letters to deepen characters and relationships. When we write our thoughts down, we organize our thoughts and say what we really mean. It's likely that a letter to a friend (or enemy) will be more articulate and truthful than a real-time conversation. Use these letters to develop the speaker's voice and personality completely. Show us how their mind works. Think about how the writer feels about the person he's writing to, and pour the truth of those emotions into the letters. Don’t let the writer forget about the person reading the letter. If letters start sounding like diary entries, the audience won’t enjoy reading them.

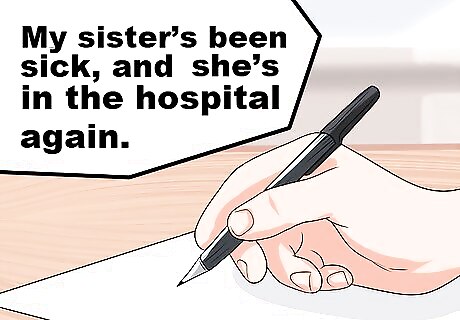

Leave gaps in the chronology for realism. Life gets in the way, even for the most dedicated of writers. As the action begins rising and the conflicts start piling up, your characters likely won’t have as much time to write as they used to. It’s just not realistic to sit down and write a letter to your best friend about an alien attack on the day it happens! After major events, allow a little time to pass before you date the letters that address them. Have the writer speak of them in the appropriate tense: “Sorry I haven’t e-mailed in a few days. My sister’s been sick, and she’s in the hospital again. The doctors say she can go home next week, but I’m still so scared.”

Choose how to format your letters. Even with something as simple as a diary entry, you have options to choose from. For example, a younger character might choose to begin every diary entry with “Dear Diary,” or even give the diary a name to make it feel more personal. An older character might just put the date at the top of the page and start writing. If you’re writing letters, you don’t have to format them like you would proper letters in real life. The reader might not enjoy seeing the return address listed on every letter.

Drafting and Revising Your Story

Create an outline. Before you begin writing your actual story, make an outline of major events so you know how the plot will progress. The outline doesn’t need extensive details, but sketch out the main points of the story. This will help you keep track of what you’re building toward as you’re actually writing the story. When does the initial conflict that sets the plot into motion occur? Usually, it happens at the end of the exposition, and kicks off the rising action. What conflicts come into play during your rising action? Each conflict should raise the stakes and the tension, building toward the climactic scene. What information do you want to include in your denouement? Anticipate the questions the reader will have about loose ends that need to be tied up.

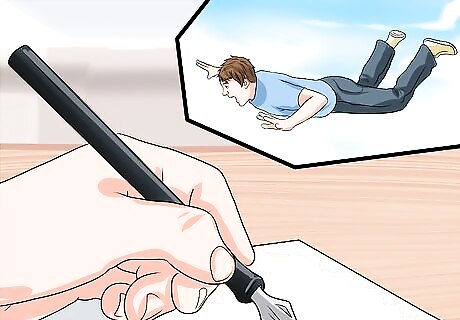

Write your first draft. Don’t worry about making mistakes in your first draft: don’t check for spelling errors, and don’t correct your grammar. When you first start writing your draft, you want to focus on getting the story right. It’s about developing your characters and building tension — the things that will make your reader emotionally invest in your story. Use your outline to remind you of how your plot needs to progress.

Don’t get frustrated. Writing a story is hard — really hard! But luckily, you don’t have to show it to anyone until you’re ready to. This first draft is for your eyes only. It’s where you’re playing with different ideas and working out how to get from point A to point B in the plot. Instead of getting hung up on how your draft isn’t polished yet, try to enjoy the process. Focus on your accomplishments. Think of how good it will feel when you finally nail this scene!

Work your way through writer’s block. Don’t feel alone! Every writer comes across writer’s block at some point or another. If even your outline isn’t helping you move past it, don’t fret. The only thing you can do is keep writing. Remember that your first draft will be heavily revised before you finish your story. You can delete as many terrible versions of a scene as you want! It may help to put this story aside for a while and write your way through other prompts. You don’t want to start another large project that might lead you to abandon this one. But free-writing about a fond memory or something interesting you say today will help get your hand moving. When you’re ready, you can come back to this story.

Revise for as long as you need to. The real work of writing comes in the revision process. Nobody writes a perfect story on the first try. A good writer will produce several drafts of the story. Give yourself time between drafts instead of writing and revising all at once. A little bit of time will give you distance and perspective. You’ll be able to see where you story is working well and where it needs more work.

Be your own toughest critic. It’s easy to fall in love with your baby. When you write something, you have every right to be proud of it and love it. But while you’re revising, you have to be cold to your own work and look ruthlessly for its flaws. Imagine you’re a reader seeing this work for the first time. Do sections of the story drag? Shorten them! Are some transitions unreasonable? For example, is it unrealistic for the love interest to fall in love with the main character as soon as she breaks up with her boyfriend? If not, do the work of ironing out those transitions. Have you used the strongest language wherever possible? Read the whole draft aloud and look for sentences that sound awkward or weak. Focus on strengthening them.

Comments

0 comment