views

Crushing a Soda Can

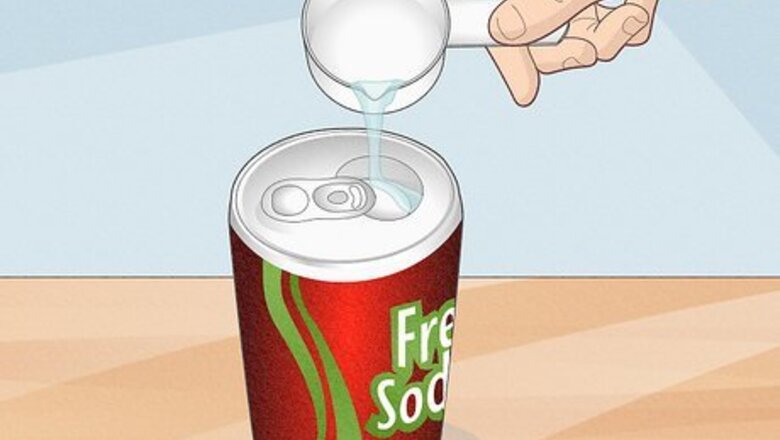

Pour a little water into an empty soda can. Rinse a soda can with water, and leave approximately 15–30 millilitres (1.0–2.0 US tbsp) of water in the bottom of the can. If you don't have a measuring spoon, pour in just enough water to cover the bottom of the can.

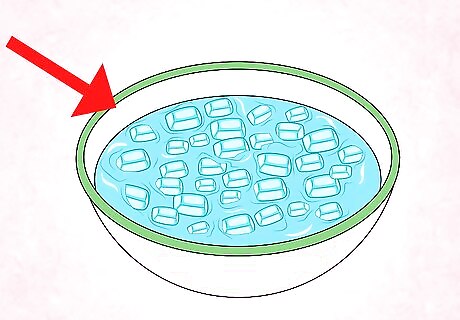

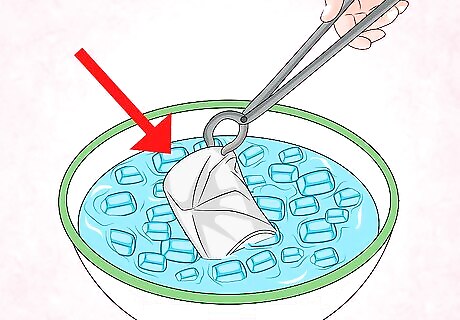

Prepare a bowl of ice water. Fill a bowl with cold water and ice, or with water that has been kept in a cold refrigerator. A bowl deep enough to hold the can might make it easier to conduct the experiment, but it is not necessary. A clear bowl will make it easier to watch the can get crushed.

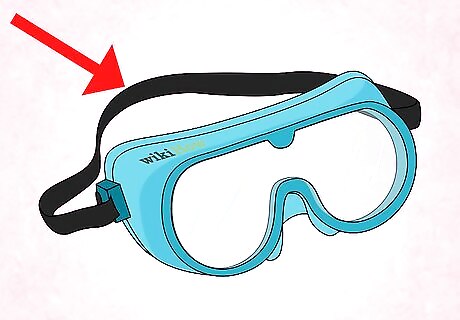

Get splash-proof goggles and tongs. In this experiment, you'll be heating this soda can until the water inside it boils, then rapidly moving it. Everyone nearby should be wearing splash-proof goggles in case hot water is sprayed toward their eyes. You'll also need a pair of tongs to grab the hot can without burning yourself, then turn it upside down into the bowl of ice water. Practice picking up the can with the tongs so you're sure they can pick up the can firmly. Continue only with adult supervision.

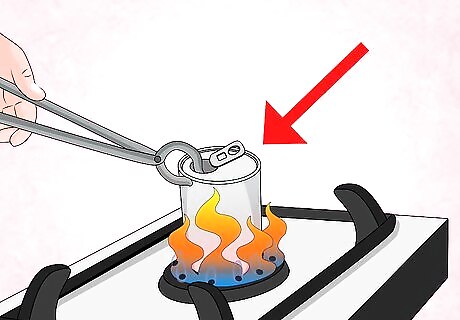

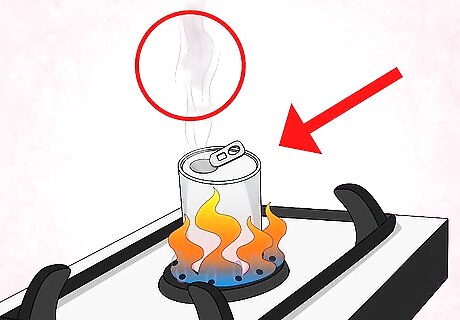

Heat the can on the stove. Place the soda can upright on a stove burner, then turn the heat setting on low. Let the water boil outside the can, bubbling and letting out water vapor for about thirty seconds. If you smell something strange or metallic, move on to the next section right away. The water might have boiled away, or the heat might have been too high, causing the ink or aluminum on the can to melt. If your stove burner cannot support the soda can, use a hot plate, or use tongs with heat-resistant handles to hold the soda can over the stove.

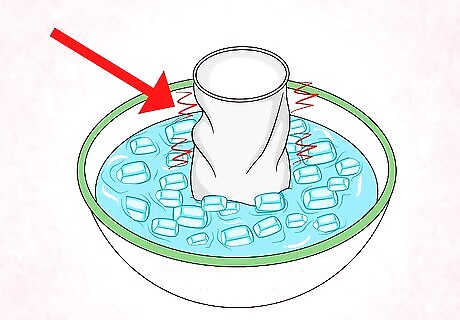

Use the tongs to turn the hot can upside down into the cold water. Hold the tongs with your palm facing upward. Use the tongs to pick up the can, then quickly turn it over above the cold water bath, plunging the can into the bowl of water. Be prepared for a loud noise as the can is rapidly crushed! Because of the sound, avoid performing the experiment around children younger than kindergarten-age.

How it Works

Learn about air pressure. The air around you is pressing against you and every other object, with a pressure as high as 101 kPa (14.7 pounds per square inch) when you're at sea level. This would normally be enough to crush a can by itself, or even a person! This doesn't happen because the air inside the soda can (or the material inside your body) is pushing outward with equal pressure, and because the air pressure "cancels itself out" by pushing at us from every direction equally.

Figure out what happens when you heat the can of water. When the water in the can boils, you can see the water start to escape as little droplets in the air, or steam. Some of the air in the can gets pushed out when this happens, to make room for the expanding cloud of water droplets. Despite the can losing some of the air inside it, it doesn't get crushed yet, because the water vapor that took the place of the air is pushing from the inside instead. In general, the more you heat a liquid or a gas, the more it expands. If it is an enclosed container so it can't keep expanding, it exerts more pressure. This is known as Gay-Lussac’s Law.

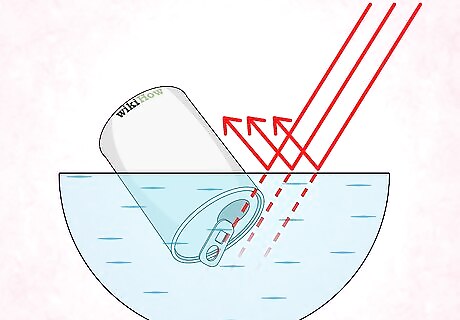

Understand how the can gets crushed. When the can is turned upside down in the ice water, the situation changes in two ways. First, the can is no longer open to the air, since water is blocking the opening. Second, the water vapor inside the can rapidly cools down again. The water vapor once again shrinks down to its original volume, the tiny amount of water at the bottom of the can. Suddenly, most of the space inside the can has nothing in it at all – not even air! The air that's been pressing from the outside of the can this whole time suddenly has nothing on the other side to resist it, so it crushes the can inward. Space that has nothing in it is called a vacuum.

Watch the can closely to discover one more effect of the experiment. The appearance of a vacuum, or empty space, inside the can has one other effect besides causing the can to be crushed. Watch the can carefully as you lower it into the water, and again as you lift it out. You might notice a small amount of water getting sucked up into the can, then trickling out again. This is because the water pressure is pushing against the opening of the can, but only hard enough to fill a little of the can before the aluminum is crushed.

Helping Students Learn from the Experiment

Ask the students why the can was crushed. See if the students have any ideas about what happened to the can. Do not affirm or deny any of the answers at this stage. Acknowledge each idea, and ask the students to explain their thought process.

Help the students come up with variations on the experiment. Ask the students to come up with new experiments to test their ideas, and ask them what they think will happen before they conduct the new experiment. If they have trouble coming up with a new experiment, help them out. Here are a couple variations that may be helpful: If a student thinks the water (not the water vapor) inside the can was responsible for it getting crushed, have the students fill an entire can with water, and see if it is crushed. Try the same experiment with a sturdier container. The heavier material should take longer to be crushed, which will give the ice water more time to fill it. Try letting the can cool for a short time before putting it in the ice bath. This will result in more air being present in the can, and thus less severe crushing.

Explain the theory behind the experiment. Use the information in the How it Works section to teach the students why the can was crushed. Ask them whether that matches what they came up with in their experiments.

Comments

0 comment