views

In school history textbooks, the political integration of India is not widely taught, often relegated to mere footnotes. Alongside the partition of India and Pakistan, the fate of princely states on both sides remained undecided. These states, comprising almost one-third of India’s land, were each recognised by the Viceroy of India, who held the authority to transfer power. Students are typically informed that only a few states, like Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Kashmir, refused to join India, and Sardar Patel took charge of the political integration. However, the reality is far more profound.

At India’s independence, many princely states posed challenges to the Indian Union. Legally, all 565 princely states had the authority to join India, Pakistan, or remain independent. Some rulers were benevolent, while others were ruthless. Convincing them to relinquish their powers was akin to squeezing water from a stone.

Jodhpur’s ruler, Hanwant Singh, was negotiating with Jinnah and was about to sign the merger with Pakistan. But a pro-Indian dewan blew the whistle, Hanwant Singh’s mother intervened, and Sardar Patel persuaded him to join India. Indore’s ruler, Yashwant Rao Holkar, was in discussions with Jinnah, and Bhopal’s Nawab, Hamidullah Khan, was brokering these dialogues. Holkar even neglected the requests of six fellow Maratha rulers, and when they visited his state to convince him, he refused to meet them.

In the south, Travankore’s Dewan, CP Ramaswamy Iyer, maintained the position of an independent state, which changed only after he was shot by a gun and hospitalised. Kashmir’s accession happened hurriedly when the state was attacked from the Pakistani side. Junagadh was freed when the state government invited the Government of India to take over, fearing the collapse. For Hyderabad, ‘Operation Polo’ became necessary to counter the threats of the Nizam and the leader of Razakars, Qasim Razvi.

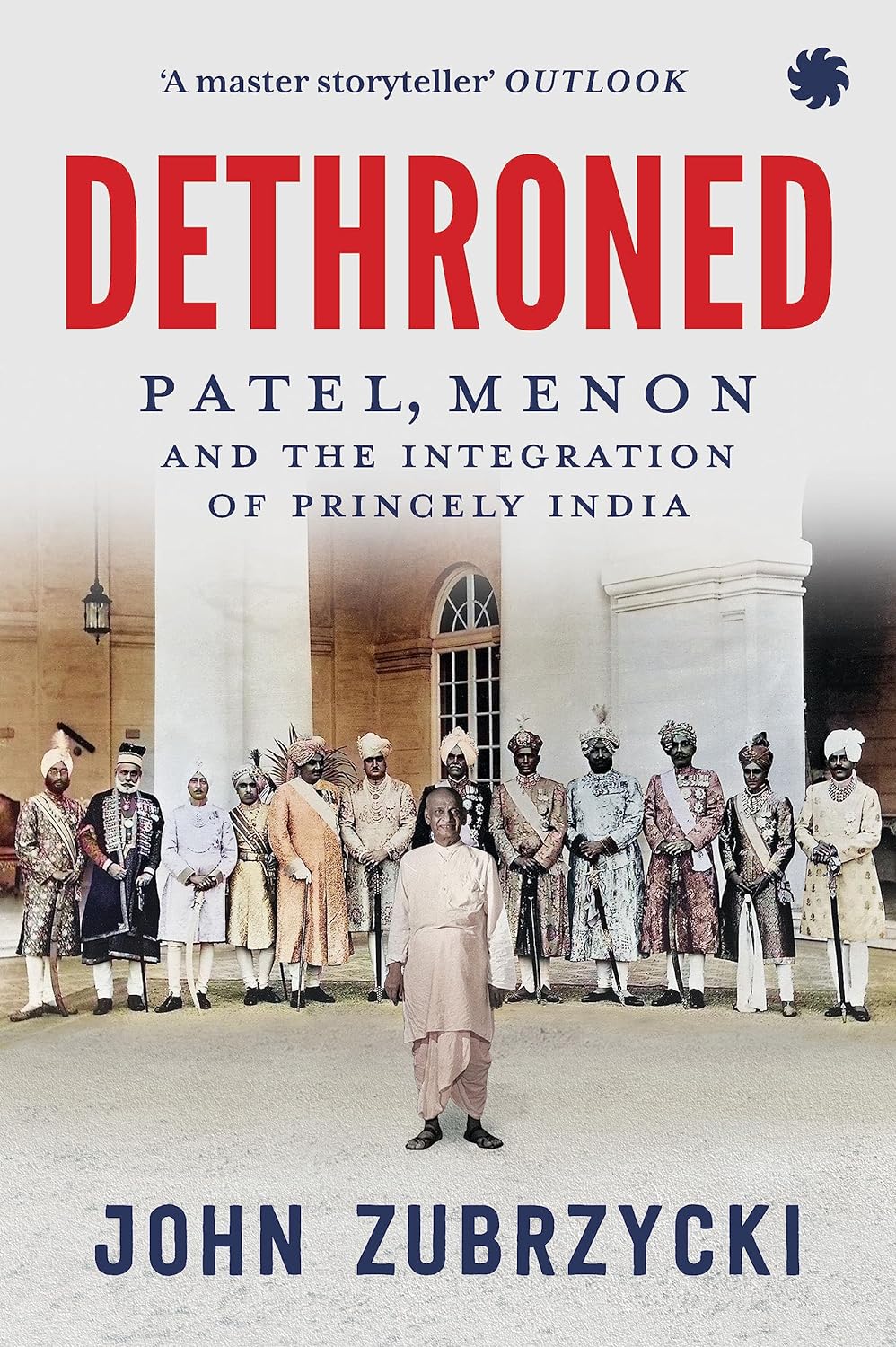

Sardar Patel and his secretary, VP Menon, wove modern India amidst these challenges. In his latest work, ‘Dethroned: Patel, Menon, and the Integration of Princely India’, John Zubrzycki sheds light on this pivotal saga. Deeply researched and persuasively presented, the book explores the multifaceted events that led these princely states to join India, relinquish their powers, and reorganise.

The foresightedness and efforts of Patel, the excellent skills of Menon, the tactical support of Mountbatten, the fear of revolt by common Indians in the mind of rulers, and, for most of the time, the distance from Nehru made this integration possible. Yes, the distance from Nehru made this integration possible!

Zubrzycki quotes an incident narrated by the then Colonel Sam Manekshaw that proves Nehru was an indecisive idealist. When Kashmir was attacked, Patel went to him to get permission for military intervention. At that time, “as usual, Nehru talked about the United Nations, Russia, Africa, God almighty, everybody until Sardar Patel lost his temper. He said, ‘Jawaharlal, do you want Kashmir, or do you want to give it away.’”

When Nehru proposed a plebiscite for Junagadh, Patel foresaw how Pakistan could exploit it against Indian interests. Patel emphasised there was no need to set such a precedent. Later, Nehru, who also handled the foreign ministry, took the Kashmir issue to the UN, disappointing Patel. The book highlights Patel’s pragmatism and Nehru’s naivety. In instances where naivety triumphed over pragmatism, India suffered, as we continue to witness.

While describing Indian rulers, Zubrzycki exhibits orientalist bias and fails to provide an objective analysis. He portrays sexually wicked, misogynistic, extravagant princes without acknowledging the noble ones admired by the public.

For instance, Maharaja Bhagwad Singh of Gondal, Gujarat, a medical doctor and a fellow at the Royal College of Physicians at Edinburgh, made his state completely tax-free in 1934. During his tenure, as Nihal Singh notes in ‘Shree Bhagvat Sinhjee: The Maker of Modern Gondal’, the number of girls admitted for primary education increased 25-fold. He also introduced electricity with underground lines, telegraphs, telephone cables, street lights, sewage, and irrigation techniques in his Gondal state in the 1920s! The Maharaja industrialised the state and funded projects like the largest Gujarati dictionary and the first Gujarati encyclopedia, Bhagavadgomandal. Mahatma Gandhi was ‘amazed by the adventure’ of Maharaja for his mother tongue, Gujarati.

Similar positive examples abound among rulers of Bhavnagar, Nawanagar, Morbi, Kutch, and Baroda.

In conclusion, the book provides a valuable understanding of Patel and Menon’s roles in India’s political integration. Without this integration, obtaining permission from hundreds of kings for events like the Char Dham Yatra would be necessary. Knowing these lesser-known historical chapters enriches readers, and Zubrzycki’s narrative style adds to the enjoyment. After reading this book, the least a reader can do is not take the Republic of India’s integrity and unity for granted.

The writer is an independent columnist who writes on international relations, and socio-political affairs. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment