views

New Delhi: The Andaman & Nicobar Police is facing a huge dilemma. Even the Constitution of India has no clear answer for it. The force has to choose between its legal obligations and a much bigger moral obligation.

If it strictly follows the Indian laws then it will be forced to arrest a Jarawa man for the murder of a baby boy. It is something never happened before. In the nearly 200 years of British and later Indian rule, no Jarawa has ever been charged with any crime by the police. The moral obligation says "don't interfere. Just leave them to live in their own world which has nothing to do with modern world".

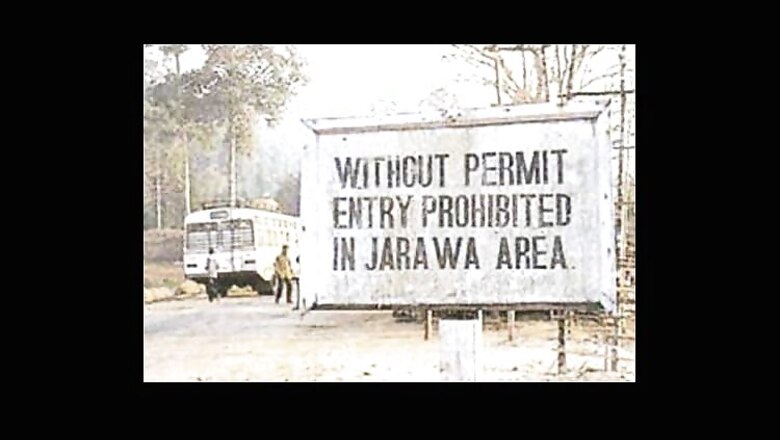

Jarawas of Andaman & Nicobar islands are the last remnants of Paleolithic ear civilization. Numbering about just 400, they are believed to have migrated to Andaman & Nicobar islands around 50,000 years ago.

They live in 300 square miles of forest in the Union Territory and survive by hunting and gathering forest produces. They rarely interact with the outside world and till recently, they used to attack the outsiders with a bow and arrow. In the last two decades, Jarawas have been interacting with the outside world and accept modern medicine, food etc.

The police don't know whether to apply Indian laws to them or just ignore the "murder" of a five-month-old baby mixed race baby.

According to "New York Times" the police on South Andaman Island know what to do when members of the isolated Jarawa tribe venture into the villages that surround them, hoping to snatch rice and other prized goods, like cookies, bananas or, for some reason, red garments. But this did not prepare police officials for the criminal complaint that was registered at the police station in November.

A 5-month-old baby was dead, and witnesses came forward willingly, leaving the police, for the first time in history, confronting the prospect of arresting a Jarawa on suspicion of murder.

The Jarawas are very dark-skinned, small in stature and until 1998 lived in complete cultural isolation, shooting outsiders with steel-tipped arrows if they came too near.

After the tribe made peace with its neighbours, Indian government took steps to minimize contact between the Jarawas and the world that surrounds them, hoping to avoid the catastrophes that befell aboriginal people in other countries, like the United States and Australia, when settlers passed on germs and alcohol.

Nevertheless, contact is occurring. Outreach workers visit the tribe's camps, and Jarawas receive medical treatment in isolation wards at hospitals. Poachers strike up illegal relationships with members of the tribe, trading food for help in harvesting crabs or fish.

It is as a result of such an encounter, the police believe, that a baby boy with a lighter skin color than usual was born to an unmarried Jarawa woman in 2015, evidence that alien genes had found their way into an undiluted pool.

The NYT reports adds that among the first to be alerted about the birth of a mixed-race baby was M Janagi Savuriyammal, a 24-year-old tribal welfare officer whose office sits beside a crocodile-infested creek at the edge of the tribe's reserve. It is no secret that the tribe has, in the past, carried out ritual killings of infants born to widows or — much rarer — fathered by outsiders.

Dr Ratan Chandra Kar, a government physician who wrote a memoir about his work with the Jarawas, described a tradition in which newborn babies were breast-fed by each of the tribe's lactating women before being strangled by one of the tribal elders, so as to maintain "the so-called purity and sanctity of the society."

He said he was aware of at least seven such cases in his 12-year tenure. The faces of the children haunted him, he wrote in his book, but he added that he was "never ready to interfere in the customs and rituals of the tribe."

Savuriyammal took a different view. When she learned that some members of the tribe "did not want the baby to grow up," as she put it, she and her staff began a campaign of persuasion, presenting arguments against killing the child and, at one point, posting a social worker near the Jarawa camp to watch over him.

She was not the only one who felt the child was in danger. Rooby Thomas, who oversees care of Jarawa patients at a hospital near the reserve, saw the baby when his mother brought him in for a checkup and was so alarmed when she saw his skin tone that she set up a screen to hide him.

"I isolated that baby from the other Jarawa," she said. "I heard they usually kill non-Jarawas."

The Centre is yet to comment on this. Certainly our Constitution has no solution to it as allowing Jarawas to practice their stone age lifestyle is more important than making them a part of modern criminal justice system.

Comments

0 comment