views

Lemon peels in warm water pass for finger bowls in your local restaurant. But for Sitala and her three children, it’s dinner. On a good day, they can relish some salt with it.

The family in Sevatand village of Jharkhand’s Giridih district is on the brink of starvation. But, god forbid, if any of them does succumb to acute hunger, the death would be marked down to malnutrition, tuberculosis or stomach disorder.

Because, as far as the state government is concerned, no one dies of starvation in Jharkhand.

For the government, even the death of Budhni Soren in January this year was “so-called starvation death".

Budhni, a tribal woman, had spent her last days scouring for edible leaves in the nearby forest. She wasn’t allowed to share her seven-year-old son’s mid-day meal at his school. When she couldn’t kill her hunger, the hunger killed her.

But authorities are in denial. According to Giridih Deputy Commissioner Manoj, it cannot be called ‘starvation death’ unless the whole family dies.

“None of these deaths have been established as starvation deaths. Around a month ago, the death of Savitri Devi was also said to be a so-called starvation death. But she had a whole family. If it was starvation, it should have struck all the members," he says.

Sitala was one of Budhni’s closest neighbours. Since sufficient food is a distant dream for her, the middle-aged Sitala now has only one hope. “I don’t want my children to be around when my body turns cold. When Budhni died, her cold body screamed of hunger. All she needed were a few morsels and even I need the same," says Sitala, furiously scrapping a mud pot in the hopes of finding a few grains of rice in it.

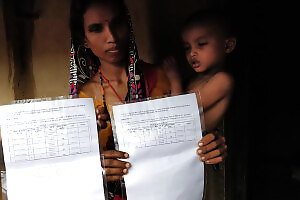

Worried for her children more than herself, Sitala walks miles every week to the PDS shop, but is turned away empty-handed. For the last two years, her Antyodaya card has proven useless even though she has been living in Sevatand village for the last 25 years.

Ramlata, another neighbour, is seated at the same spot in the dung-caked veranda where Budhni’s body was kept for hours before the local administration turned up. “How many times can you return dejected from the ration leader," she says with an air of finality.

Counting Budhni, at least 12 people have died allegedly of hunger in the last 10 months. But the Raghubar Das government has not accepted or confirmed a single one of them as ‘starvation death’ despite locals complaining of non-issuance of ration cards and authentication of PDS cards.

It’s a similar story in Ramgarh district, barely a kilometre from the Ranchi-Hazaribagh expressway. There’s a dense forest in Mandu block of the district but dwellers of the Kundaria settlement still go to bed hungry.

The 200-odd people of this settlement are mostly women, children and the elderly. The men work as labourers in Ranchi and other cities, struggling to make a living which barely sustains them, let alone their families back home. Bamboo sticks covered by dried leaves is home for these people. No food, no pucca home and no definite source of income, survival is a daily struggle for them.

The struggle proved too much for Chintaman Malhar, a man in his late 50s. He passed away this June after battling hunger for three days.

His son Bideshi Malhar says the old man got his hands on some stale food on the eve of his death, but it wasn’t enough to sustain the frail man.

Macabre as it may be, Malhar’s death brought some respite for his neighbours. Each family was given 10 kg rice by the Block Development Officer, says Radha.

But the respite was short-lived as monsoon threatens to spoil the grains. The villagers’ only hope is pinned on a sheet of plastic covering the makeshift tent where the grains are stored. Radha and four others are cooped up in here in heavy downpour sorting the rice. “None of us have a bank account. We were never even listed for PDS," she says.

Mansa, another resident, is in her early 20s but has already lost two children to malnutrition. “After Malhar’s death, they are enrolling us for ration cards and have given us 10 kg rice," she says, hoping that it’s enough to keep her last surviving child alive.

Malhar’s fate echoes in Sonpurwa village of Garhwa district where 67-year-old Etwariya Devi died on December 28 before her daughter-in-law could procure some food. The latter had been trying for three months to get ration from the local dealer, but in vain.

When at last the family managed to borrow some rice, Etwariya Devi died before she could consume it. Her son Ghura Vishwakarma now runs a small grocery store from a room in their home after taking a loan of Rs 50,000.

Etwariya Devi was a pensioner under the Indira Gandhi Old Age Pension Scheme, but the last time she had received her pension from the local Pragya Kendra was in October. After that, each time she went to the Kendra seeking her pension, either electricity played spoilsport or she would be asked to come another day. Etwariya didn’t get to live till that elusive day.

One would think that social security pensions and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act would be lifesavers. But most villagers and tribal people have stopped banking on them, complaining that payments are hardly made.

Even the government agrees that the coverage of these schemes isn’t universal. “As per the National Food Security Act, we have been given a mandate to cover 86% of the rural population under PDS. It is based on the 2011 Census and according to the projected population it covers 85%. This means the remaining population cannot be covered," a senior Jharkhand government official told News18.

CASTEISM COMPOUNDS THE CRISIS

Itkhori villagers remember Meena Musahr as the woman who begged for food next to the Mahua tree. Meena was dying of hunger but the villagers never realised as they never spoke to her.

“We never spoke to Meena because she was of a different caste. She generally begged and had food, but we don’t get ration at all," says Shanti, who has just built her own home with a loan of Rs 50,000 from the local moneylender. She now earns a living polishing utensil.

“We sell these utensils in the dehat. Even we bear hunger for a few days," says Shanti. Ironically, she admits that Meena’s death made the authorities take notice. “Just after her death, police came in large numbers and got our ration cards made."

But there’s one person who didn’t qualify for the ration card and he wonders why. Ramvriksh is frail and his chalk-thin limbs are hardly able to sustain his feeble weight. Abandoned by his son years ago, he now gets by the food the Block Development Officer gives him sometimes. “But how long can that continue? I am hungry for the last few days and will die very soon," he says.

He now sits under the same Mahua tree and remembers Meena vaguely as the “woman who died begging for food". Ironically, it’s her black shawl he’s wearing.

Meena’s death, too, wasn’t deemed as starvation death. Dr Arun Kumar, who looks after the community health centre in Chatra, says the food “tribals often eat in the jungles" puts their life in jeopardy.

Dr Vandana Prasad, founder secretary of Public Health Resource Network, sees through this old excuse. “I have spent 25 years working with doctors at ground zero and that’s a very fallacious claim. It’s only when people are suffering from acute starvation that they eat aam ki gutli etc and then the post-mortem shows some grass in their stomach. This can’t be used to rule out starvation and only show their insensitivity," she says.

FAILED BY THE PDS

Dr Prasad rubbishes another such claim made in the case of Premani Kunwar, who died in December in Jharkhand’s Korta village. Thanks to the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna, residents here have dwellings but they wonder how long they can survive with the PDS in disarray.

Premani Kunwar’s son says his mother died as she hadn’t received her late husband’s pension for two months and the local ration dealer stopped issuing her the quota of grains she was entitled to.

Premani was her husband’s second wife. Her stepsons and their wives live nearby. So couldn’t they have given her some food? “Should we have given her to eat when we don’t have anything ourselves," says one of Premani’s step daughters-in-law as she ignites the chulha.

Soon after her death, the widow’s pension that was denied to Premani started being credited into the account of her husband’s first wife.

Post-mortem investigation revealed the presence of ‘grains’ in Premani’s stomach, which was used to deny her son’s claims of it being a starvation death. But Dr. Prasad says it proves nothing.

“It could be anything she ate to kill her hunger. That does not mean there was no acute malnutrition. It’s a vicious cycle. You get more malnourished and you get sicker. You cannot even crawl to the PDS shop to claim your share," she says.

Given the mounting complaints against the PDS network, the state’s Food and Civil Supplies Department had on March 5 notified a nine-member panel to submit recommendation on improving the system. The team was given the deadline of April 30, but more than two months since, the report is still awaited.

AGE NO BAR, PLACE NO BAR

Starvation in the state is neither limited to the elderly nor to the villages. It was 11-year-old Santoshi Kumari’s death in Simdega last year that served as a wake-up call. In the coal mining hub of Dhanbad, hunger claimed the life of Baijnath Ravidas. In his 40s, the rickshaw-puller left behind five children, the oldest being 20 and the youngest being eight.

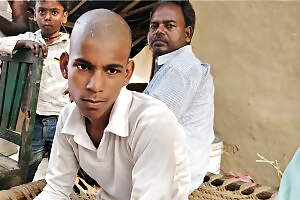

Their house is barely holding up behind Gate No 6 of the coal mining belt. Suraj Kumar, 14, remembers his father Baijnath asking for food in his last few hours, but with nothing at home, the family went begging for some.

“He died of hunger. There was no food for three to four days. My brother started working at a tyre repair shop after my father’s death," Suraj says.

Unlike other bereaved families, however, Baijnath’s eldest son Ravi doesn’t want to make loud claims of the starvation death. What’s the point, he says. “What will happen even if we scream that he died of hunger? We did not have any ration card when he died. Now we have been issued one. Let it be."

After Baijnath’s death in October, Dhanbad Deputy Commissioner A Dodde gave the family Rs 20,000 and assured 50kg of food grains immediately, but didn’t budge from the denial. “He (Baijnath) was sick for one month. After reports of his death, a probe was conducted. It was found that he died of illness and not hunger," Dodde had said then.

Even today, Baijnath’s widow Parvati struggles to receive his pension. “I have visited their office a couple of times since November, but got nothing till date. Maybe they will give me soon," she says.

12 AND COUNTING…

Hunger is now a serial killer in the state with the latest victim being Savitri Devi of Giridih district, the same where Budhni Soren breathed her last.

When Savitri Devi died on June 2 inside her dilapidated home in Mangargarhi village, it came to light that she didn’t have a ration card and hadn’t been able to access her widow’s pension. Her daughter-in-law Purnima Devi cannot believe that the death didn’t ‘qualify’ as one caused by starvation.

“We did not cook at home for three days. There was nothing to cook. Our stomach is empty on most days," she says. Her husband and Savitri’s son works in Jharkhand and could return only after the death, but Purnima remembers the futile trips to local ration shops.

“She died of hunger. I don’t know why the government is denying it. Though we have been issued temporary ration cards, we still yearn for food," says Purnima.

Her plight is shared by her neighbours. “Savitri Devi indeed died of hunger. They hardly had any food for 15 days. How long could we help them? We needed to eat too," says 35-year-old Somri Devi, who lives just two houses away.

When News18 paid a visit to the local ration dealer, Nand Kishore, he said he had no knowledge of any family being denied food grains.

“We always give ration to anyone who has the ration card and whose fingerprint matches that of the POS (Point of Sale Terminal) machine. If all that fails, we even have a record book where we write down the name of the ration cardholder and issue them the produce. But if someone doesn’t have a card, what can we do?" he asks.

Somri Devi says that after Savitri’s death, the families in the vicinity were issued temporary ration cards.

In this case, too, Giridih Deputy Commissioner Manoj stuck to his logic. “How can it be called a starvation death when other family members like her two daughters-in-law and sons are alive? If it were indeed a case of starvation death, the entire family would have starved," he

says.

As Savitri’s daughter-in-law retreats into the darkness of her home, a colourful truck outside is doing the rounds, with officials distributing free LPG cylinders to select families. As the truck honks, an angry Purnima shouts, “Horn kam bajaa. Daana nahi hai. Kya pakayen? Khud ko? (Don’t honk so loudly. We don’t have a single morsel. What do we do with the cylinder? Burn ourselves?)

(Image: Debayan Roy/News18.com)

(This story is part of a series by News18 on the starvation deaths in Jharkhand)

Comments

0 comment