views

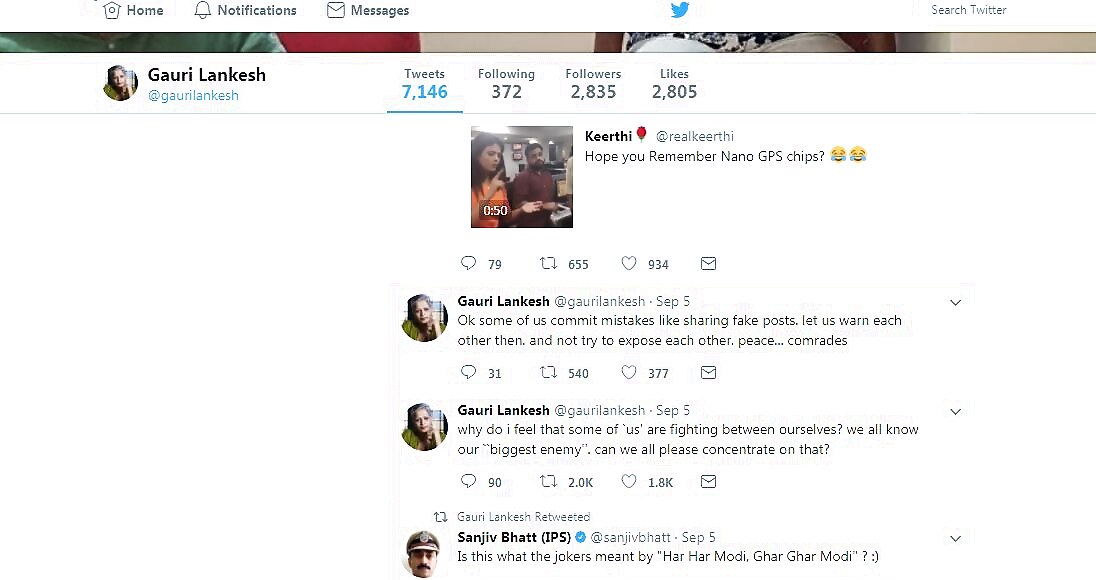

"Why do i feel that some of 'us' are fighting between ourselves? we all know our "biggest enemy". can we all please concentrate on that?" This was Gauri Lankesh's last tweet.

She was shot dead the same evening. It doesn’t really matter who killed her. That a person lost her life for a cause that mattered the most to her — individual freedom, liberty and secularism — is sufficient to right all her wrongs.

She had it in her genes — the good, the bad and the ugly. I knew her father before I knew her. That was in 1985. I was a student of journalism. The Times Research Foundation Institute took us down south on an educational trip in December. An escape from the chilly environs of Delhi to the impossible warmth of wintry Bangalore.

We were put up at the IIM hostel. The would-be graduates were out. Their semester had ended. On the morrow of our arrival, we went to a locality. I forget the name. It was an office with no pretense of being an office. No signboard. No name plate. The door opened and a tall man came out. He was expecting us. Nice smile. Welcoming. The moustache and the wispy hair on his head made him look older than his age.

'Lankesh', he introduced himself. The editor of the eponymous weekly, Lankesh Patrike. He wasn’t a journalist. He was an English lecturer until he couldn’t handle the plight of the poor of his Karnataka and decided to do something about it. He wouldn’t seek advertisements for his publication. He wouldn’t be afraid of anyone. He launched not just a publication, but a revolution. That involved a simple formula: Tell the truth.

We spent over an hour with him. He explained the economics of publishing the Patrike. He was more worried about how to increase the subscriptions. He wasn’t worried at all about those he rubbed the wrong may. 'They won’t dare to do something to me'. They didn’t do anything to him. They targeted his daughter.

To cut a long story short, as we boarded the bus back to where we were going next, we heard a few giggles. At least I did. I’d know years later one of them belonged to Gauri. Lankesh’s elder daughter.

Fast forward to 1987. November, to be precise. I was married to Sudha, my classmate at journalism school. Our batchmates threw a party to celebrate our marriage at the residence of Gauri of all people. And of all places, in Defence Colony, New Delhi.

It was a crazy night. Many of those attending the party that night are big names today. That aside, what I recall is Gauri. Thin, reed thin. The longish nose smug on her small face. The crow’s feet widening as she raised a smile. She wasn’t beautiful. She was attractive. More than that, she had a personality. She commanded attention. The voice would reach a baritone as easily as it would shrill out an invective. Moody. Benevolent. Liberal. Woman. Fighter. Journalist. Humorist.

What I remember most of that night is her peck on my cheek. Sudha got a hug, though. Be happy, she told us. We were strangers till then. Never again, because she struck up a bond. The party was peaking. Noise. Humdrum. Shouts. Singing hoarse. A neighbour called the police. A friend, who would later advise a Prime Minister, placated the khaki chaps. The night ended on that note.

We found our paths crossing a decade later. I was with Eenadu Television. I had launched the news division in Telugu in Delhi. The Kannada one was on the anvil. That’s when I found some of our colleagues talking to an “expert”. Who, I asked. 'Gauri Lankesh. She’s a journalist and filmmaker and a very tough lady,' these chaps replied. My face creased in a knowing smile. I met her soon. She’d come to ETV studios for analysis or discussions. Her approach to analysis was clinical: acquaint herself with all sides of the coin; introduce her opinion and back it up with facts; respect contrarian views.

A few years down the line, Lankesh passed away. Passed the baton to his children. They went through troubled times trying to identify Lankesh’s true successor. The other daughter, Kavita, was, and is, a filmmaker. Gauri dabbled in it too. Their brother, Indresh, was good at both — print and visual. Anyway, that is not germane to this piece.

Suffice to say, Gauri decided to be what her father was; not what her father wanted her to be. She wasn’t a narcissist to name her tabloid Gauri Lankesh Patrike. It was a daughter who missed her dad and tried copying him. She copies his ideas too.

I am getting ahead. There came a time in the new millennium that Gauri needed a respite from family and feuds and friends. She came to Delhi. She joined Headlines Today (it changed to India Today, the news channel, years later). She’d sub copy. Yes. There used to be a copy desk in news channels those days! Senior journalists used to man that desk. She’d go out and report. She’d be happy to be an in-house analyst. Nothing was beneath her. It was journalism. It was dedication.

A week into her job, her colleagues found out she was no pushover. No walkover, either. She had a patented attire — skin tight Levi’s and most often, a loose white shirt. The sleeves rolled up to show her straw-like arms. A close cropped head gear, “kaajal” in her eyes and a beaming smile. That summed her up.

She could out-drink any male, as we found out to our dismay, she wasn’t beautiful, she was attractive. I’d accompany her to the Press Club often and end up discussing singer Janaki’s songs or the works of Marquez or Lolita or Nehruvian socialism. She was a staunch Kannadiga and had an earthy unfeeling for Tamil Nadu’s stand on Cauvery waters. For a person who’d never worked in Delhi as a journalist, she had a lot of friends, among politicians and bureaucrats alike. Those from Karnataka, well, they knew her. Not the other way around!

I used to head Assignment – the input desk – in the channel those days. I introduced myself. Remember, Defence Colony, that 1987 night? Oh, yes. The bond again. We became friends. We’d talk politics, sociology, economics. I’d talk of breaking news and she’d raise her eyebrows. What the hell’s that? Oh, nothing really but it is any information that we think only our channel has, I’d tell her. Why should the anchors have so much make-up, she’d wonder. What has that got to do with news? Wonder why all anchors happen to be fair, with dark hair and long eyelashes? Her wonderment never ceased as she digested surprise after surprise in a Delhi TV newsroom.

She was politically sound. Politically correct. Intuitive. Law was something else she understood. That’d give her some mental strength a few years later when two members of Parliament would drag her to court.

Gauri liked kids on the block. Straight for the slaughter, she’d amuse herself as the editor or whoever gave a tongue-lashing to the interns. She’d spend time with them. Explain the rudiments of journalism. Try re-write their copy or point out the errors in visual sequencing. She knew a lot about TV production.

But above all, she loved telling them about her father. What he stood for. Be fair. Be liberal. Be just. Be courageous. What you write or show on TV should merely inform the readers or the viewers. Let them come to a conclusion. You don’t have to give your opinion. It’s not needed. But there were a few 'No, Nos' for her. Child abuse. Insulting women. Neglecting the poor. Unaccountability of the government. And communalism. Oh, how she hated anyone or anything that tried to pit a religion against another in the name of nationalism! She’d go berserk. She’d lose her cool and convince people, even her critics, the importance of peace. The homilies wouldn’t end.

They won’t end, either. The media, today, is much maligned. For reasons known and unknown. But the media will be that much stronger so long as its torch-bearers are like Gauri. The Gauri I know did not get the time to defend herself as her executioner peppered her with bullets; else it would be the killer I’d be writing about. Peace be with her.

Comments

0 comment