views

Mess with the audience’s expectations.

Banter is all about gently playing with what’s expected. If you’re too on-the-nose, your dialogue won’t come across as banter. Think about what the audience would automatically assume your character is going to say, and then deviate from that slightly. Keep in mind, it’s only banter if it’s good-natured and fun. If it’s snippy or curt, it’s just good old-fashioned wit. John: “Oh, I’ll get my homework done. You have to have a little bit of faith in me.” Jane: “Faith? I’m agnostic with you. I’m not sure you’ll do it, but I have no way to tell one way or the other.” Here, Jane takes the phrase “have a little bit of faith” and turns the corner with it by describing herself as agnostic. not. The audience is used to hearing idioms about having faith, so they don’t expect Jane to make a religious reference.

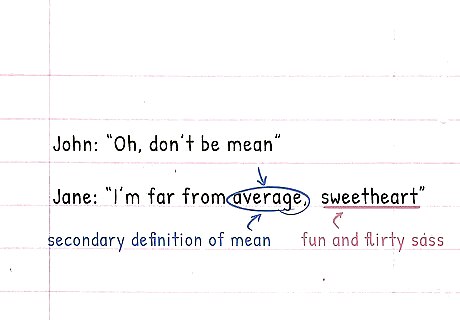

Use playful sass to elevate a moment.

Banter often rides the line between rude teasing and flirting. A quick-witted jab can build tension and demonstrate character traits. When utilized correctly, this can really make the relationship between two characters seem vivid and alive. John: “Oh, don’t be mean.” Jane: “I’m far from average, sweetheart.” While John is obviously referring to Jane not being kind, Jane flips it with her line by treating “mean” to be “average,” which is a secondary definition. The addition of “sweetheart” turns an otherwise braggy comment into fun and flirty sass.

Exaggerate in a whimsical way.

Overstating can underline that a phrase isn’t meant to be literal. A lot of banter takes place in the layer right below whatever is literally being said. By having a character exaggerate in a playful way, you’ll emphasize that whatever they’re saying isn’t intended to be 100% serious. This flags your audience to the fact that banter is taking place. John: “You’re looking chipper this morning.” Jane: “Woodchipper, maybe. I barely got any sleep last night.” Here, the audience would read “chipper” to mean “upbeat.” John is being sarcastic, but if Jane responded with snark it wouldn’t read as playful. Jane’s reference to a “woodchipper” to implies she’s torn to shreds, which is ridiculous.

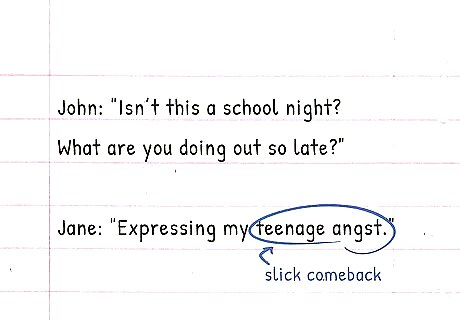

Use callbacks unexpectedly.

If you craft a memorable moment, return to it later. A callback is a comedic reference to something that happened earlier in the story or plot. It’s an easy way to put a smile on your audience’s face, and it’s a great way to reuse material that works. Imagine these characters are adults. John: “Isn’t this a school night? What are you doing out so late?” Jane: “Expressing my teenage angst.” Jane: “Hey John, what are you up to?” John: “Oh, not much. Just expressing my teenage angst.” The “school night” line is pretty playful on its own, but the “teenage angst” bit is a slick comeback. John flips it around on Jane later in a slick, silly way.

Dispense some humor in a tense situation.

Craft banter around the action taking place in the plot for a fun twist. Sometimes it isn’t just what someone says, but when they say it. If your characters are in a setting or situation where the tone is serious, or even dangerous, throwing out some unexpected banter can catch your audience by surprise. Picture John and Jane walking into court to be witnesses for a criminal case. John: “Man, I’m really nervous. I’ve never taken the stand before.” Jane: “Oh, it’ll be fine. You take stands all the time. Just the other day I watched you stand up twice. You’ll be fine.” Here, you’d expect Jane to reassure John that it’s going to be okay, and the “Oh, it’ll be fine” leads you to expect that much. What comes next is a silly (and kind of terrible) joke, which is totally out of left field given the situation.

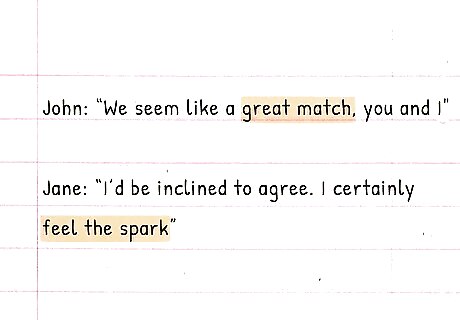

Utilize double entendres.

Any kind of double-meaning can emphasize the playfulness. When characters use any kind double-talk, it can imply that they’re being intentionally coy or evasive. When it comes to flirtatious banter, this is a great way to set the stage for a relationship to move forward or build tension. John: “We seem like a great match, you and I.” Jane: “I’d be inclined to agree. I certainly feel the spark.” John means “match” as in a romantic pairing. Jane’s reference to a “spark” implies that she’s into him, but also lines up perfectly with a match (the kind you start fires with).

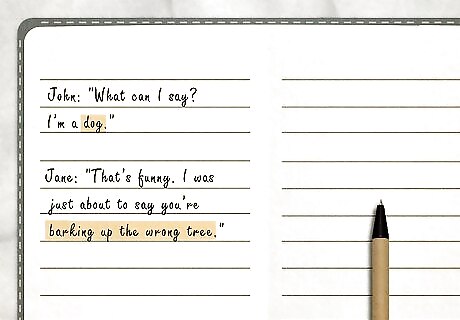

Allow subtext to speak for you.

Going out of your way to make banter “funny” usually backfires. There’s an old adage that explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better, but the frog dies in the process. Don’t dissect your banter by being too forward with it or over explaining . Your audience is smart enough to pick up on what’s going on. John: “What can I say? I’m a dog.” Jane: “That’s funny. I was just about to say you’re barking up the wrong tree.” John’s reference to being a dog is a self-burn about chasing multiple romantic partners. Jane’s insistence that he’s “barking up the wrong tree” implies he’s not getting anywhere with her. It’d be a lot less interesting or playful if Jane just said, “You’re gross” or something like that.

Rely on banter to advance the plot.

Banter for banter’s sake is fun, but it’s not productive on its own. It’s fine to use a little bit of wacky dialogue to develop a character, but once a trait is established, you don’t need to overdo it. Ideally, use banter to push the plot forward—either by establishing a conflict, driving a character to make a decision, or revealing a key detail. Take the previous example, for instance (“That’s funny. I was just about to say you’re barking up the wrong tree”). This line of dialogue works on its own, but it also establishes Jane’s disinterest in entering a relationship with John. There’s a conflict! There’s nothing wrong with taking normal dialogue and punching it up with some fun banter, but try to avoid writing so much banter that the audience becomes bored. Less is often more, here. There’s a realism element to this, too. People rarely use clever quips and coy jokes in everyday conversation with any kind of major frequency.

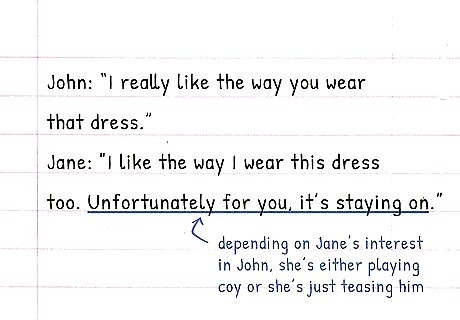

Keep banter lighthearted and casual.

If banter is too aggressive or cruel, it’s just bickering. A lot of people make the mistake of thinking bickering and banter are the same thing. A good rule of thumb here is to ask yourself, “Why is the character being witty here?” If the answer is to be “mean,” “to complain,” or “to be divisive,” it’s not banter. John: “I really like the way you wear that dress.” Jane: “I like the way I wear this dress too. Unfortunately for you, it’s staying on.” This is a good example of dialogue that might be banter depending on the tone of the scene. If Jane is established to be interested in John romantically and the audience knows she’s playing coy, this is banter. If we know John has no shot and Jane isn’t interested in him, this is just teasing.

Skip the offensive stuff.

Banter should never shock the audience by being inflammatory. It doesn’t really matter if it’s “just a joke.” You aren’t adding anything to your work by making a character intentionally cruel or offensive. Good banter is like an elegant cocktail—it should go down smooth, not knock your head back and cause a headache. This isn’t to say that you can’t have problematic characters if it’s relevant to the theme and goal of the work. But like any good chef, weigh your ingredients carefully when you’re adding some spice.

Comments

0 comment