views

Pre-Writing

Read the assignment closely. It's important to get a clear understanding of what your teacher expects from your composition in both for topic and style. Keep your assignment sheet with you whenever you're working on your composition and read it closely, paying attention to what questions you specifically have to answer—sometimes you’ll need to address all parts of a question, while other prompts allow you to pick and choose. Ask your teacher about anything you feel unsure about. Make sure you have a good sense of the following: What is the purpose of the composition? What is the topic of the composition? What are the length requirements? What is the appropriate tone or voice for the composition? Is research required? These questions are good for you to ask.

Plan to divide your time into 3 equal parts. Writing in “stages” can help your assignment feel more manageable and help you control your time effectively. Plan to spend about ⅓ of your time and effort on the 3 individual parts of: Pre-writing: gathering your thoughts or research, brainstorming, and planning the compositions Writing: actively writing your composition Editing: re-reading your paper, adding sentences, cutting unnecessary parts, and proofreading

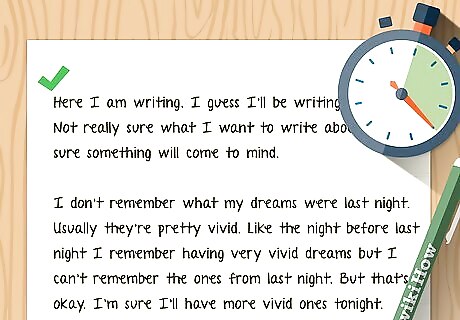

Do a free-write or a journaling exercise to get some ideas on paper. When you're first getting started trying to figure out the best way to approach a topic you've got to write about, do some free-writing. No one has to see it, so feel free to explore your thoughts and opinions about a given topic and see where it leads. Try a timed writing by keeping your pen moving for 10 minutes without stopping. Don't shy away from including your opinions about a particular topic, even if your teacher has warned you from including personal opinions in your paper. This isn't the final draft!

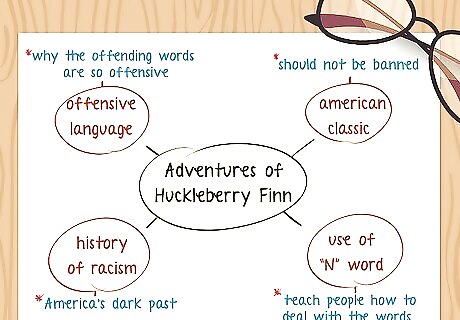

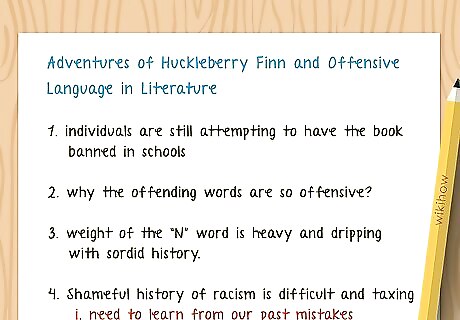

Try a cluster or bubble exercise. A web diagram is good to create if you've generated lots of ideas in a free write, but are having trouble knowing where to get started. This will help you go from general to specific, an important part of any composition. Start with a blank piece of paper, or use a chalkboard to draw the outline diagram. Leave lots of room. Write the topic in the center of the paper and draw a circle around it. Say your topic is "Romeo & Juliet" or "The Civil War". Write the phrase on your paper and circle it. Around the center circle, write your main ideas or interests about the topic. You might be interested in "Juliet's death," "Mercutio's anger," or "family strife." Write as many main ideas as you're interested in. Around each main idea, write more specific points or observations about each more specific topic. Start looking for connections. Are you repeating language or ideas? Connect the bubbles with lines where you see related connections. A good composition is organized by main ideas, not organized chronologically or by plot. Use these connections to form your main ideas.

Start with whatever idea is most interesting for a strong, innovative paper. When you’re first brainstorming for your paper, try to hone in on what you think is the strongest or most interesting idea you have. Start by outlining free-writing about that part, then build outwards to develop ideas for the rest of your paper. Don’t worry about coming up with a polished thesis statement or final argument now; that can come later in the process.

Make a formal outline to organize your thoughts. Once you've got your main concepts, ideas, and arguments about the topic starting to form, you might consider organizing everything into a formal outline to help you get started writing an actual draft of the paper. Use complete sentences to start getting your main points together for your actual composition.

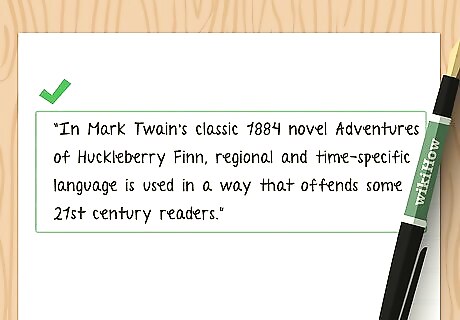

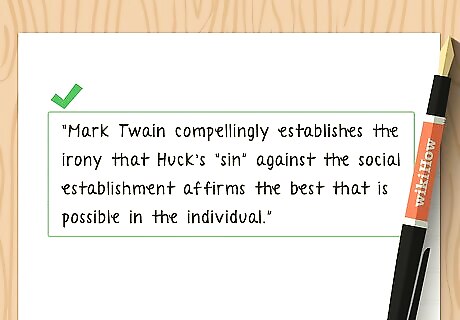

Write a thesis statement. Your thesis statement will guide your entire composition, and is maybe the single most important part of writing a good composition. A thesis statement is generally one debatable point that you're trying to prove in the essay. Your thesis statement needs to be debatable. In fact, many thesis statements are structured as the answer to a well-formulated question about the topic. "Romeo & Juliet is an interesting play written by Shakespeare in the 1500s" isn't a thesis statement, because that's not a debatable issue. We don't need you to prove that to us. "Romeo & Juliet features Shakespeare's most tragic character in Juliet" is a lot closer to a debatable point, and could be an answer to a question like, “Who is Shakespeare’s most tragic character?” Your thesis statement needs to be specific. "Romeo & Juliet is a play about making bad choices" isn't as strong a thesis statement as "Shakespeare makes the argument that the inexperience of teenage love is comic and tragic at the same time" is much stronger. A good thesis guides the essay. In your thesis, you can sometimes preview the points you'll make in your paper, guiding yourself and the reader: "Shakespeare uses Juliet's death, Mercutio's rage, and the petty arguments of the two principal families to illustrate that the heart and the head are forever disconnected."

Writing a Rough Draft

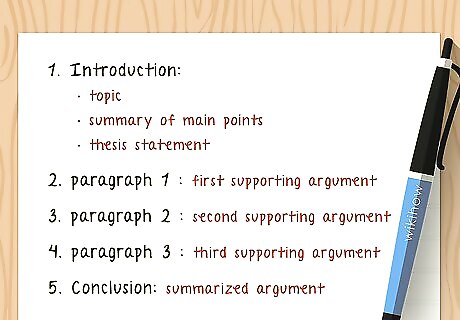

Think in fives. Some teachers teach the "rule of five" or the "five paragraph format" for writing compositions. This isn't a hard and fast rule, and you don't need to hold yourself to an arbitrary number like "5," but it can be helpful in building your argument and organizing your thoughts to try to aim for at least 3 different supporting points to use to hold up your main argument. These 3 points will all be addressed as a part of your thesis statement. Some teachers like their students to come up with: Introduction, in which the topic is described, the issue or problem is summarized, and your argument is presented Main point paragraph 1, in which you make and support your first supporting argument Main point paragraph 2, in which you make and support your second supporting argument Main point paragraph 3, in which you make and support your final supporting argument Conclusion paragraph, in which you summarize your argument

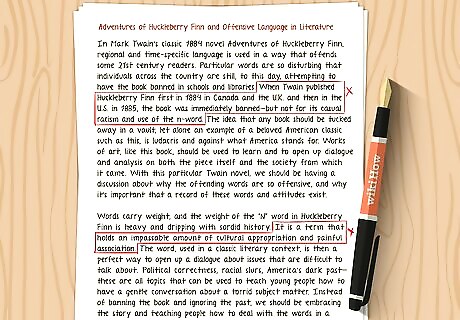

Back up your main points with two kinds of evidence. In a good composition, your thesis is like a tabletop--it needs to be held up with the table-legs of good points and evidence, because it can't just float there all by itself. Each point you're going to make should be held up by two kinds of evidence: logic and proof. Proof includes specific quotes from the book you're writing about, or specific facts about the topic. If you want to talk about Mercutio's temperamental character, you'll need to quote from him, set the scene, and describe him in detail. This is proof that you'll also need to unpack with logic. Logic refers to your rationale and your reasoning. Why is Mercutio like this? What are we supposed to notice about the way he talks? Explain your proof to the reader by using logic and you'll have a solid argument with strong evidence.

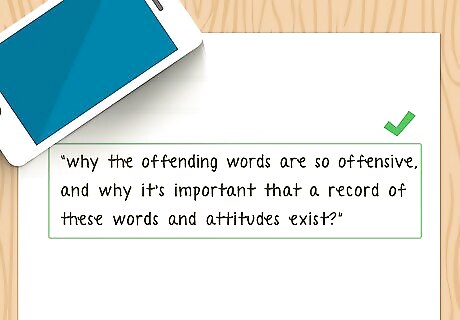

Think of questions that need to be answered. A common complaint from student writers is that they can't think of anything else to say about a particular topic. Learn to ask yourself questions that the reader might ask to give yourself more material by answering those questions in your draft. Ask how. How is Juliet's death presented to us? How do the other characters react? How is the reader supposed to feel? Ask why. Why does Shakespeare kill her? Why not let her live? Why does she have to die? Why would the story not work without her death?

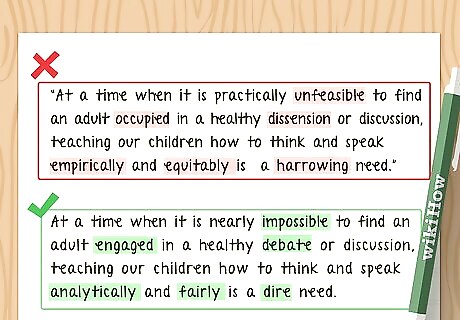

Don't worry about "sounding smart." One mistake that lots of student writers make is spending too much time using the Microsoft Word thesaurus function to upgrade their vocabulary with cheap substitutes. You're not going to trick your teacher by throwing a $40 word into the first sentence if the argument is thin as the paper it's written on. Making a strong argument has much less to do with your wording and your vocabulary and more to do with the construction of your argument and with supporting your thesis with main points. Only use words and phrases that you have a good command over. Academic vocabulary might sound impressive, but if you don’t fully grasp its meaning, you might muddle the effect of your paper.

Revising

Get some feedback on your rough draft. It can be tempting to want to call it quits as soon as you get the page count or the word count finished, but you'll be much better off if you let the paper sit for a while and return to it with fresh eyes and be willing to make changes and get the draft revised into a finished product. Try writing a rough draft the weekend before it's due, and giving it to your teacher for comments several days before the due date. Take the feedback into consideration and make the necessary changes.

Be willing to make big cuts and big changes. Revision is difficult, but it’s also essential to good writing. Many students think that revising is about fixing spelling errors and typos, and while that's certainly a part of proofreading, it's important to know that NO writer writes a perfect argument with flawless organization and construction on their first run-through. You've got more work to do. Try: Moving paragraphs around to get the best possible organization of points, the best "flow" Delete whole sentences that are repetitive or that don't work Removing any points that don't support your argument

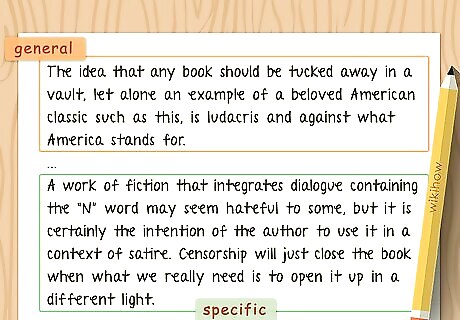

Go from general to specific. One of the best ways you can improve a draft in revision is by picking on your points that are too general and making them much more specific. This might involve adding more supporting evidence in the form of quotations or logic, it might involve rethinking the point entirely and shifting the focus, and it might involve looking for entirely new points and new evidence that supports your thesis. Think of each main point you're making like a mountain in a mountain range that you're flying over in a helicopter. You can stay above them and fly over them quickly, pointing out their features from far away and giving us a quick flyover tour, or you can drop us down in between them and show us up close, so we see the mountain goats and the rocks and the waterfalls. Which would be a better tour?

Read over your draft out loud. One of the best ways to pick on yourself and see if your writing holds up is to sit with your paper in front of you and read it aloud. Does it sound "right"? Circle anything that needs to be more specific, anything that needs to be reworded or needs to be more clear. When you're through, go right back through and make the additions you need to make to get the best possible draft.

Proofread as the last step of the process. Don't worry about commas and apostrophes until you're almost ready to turn the draft in. Sentence-level issues, spelling, and typos are called "late concerns," meaning that you should only worry about them when the more important parts of your composition--your thesis, your main points, and the organization of your argument--are already as good as they can be.

Comments

0 comment