views

X

Trustworthy Source

Mayo Clinic

Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals

Go to source

Children with reactive attachment disorder can be sad and withdrawn, not interested in typical kid activities, and resistant to comfort from caregivers.[2]

X

Research source

. Because of their early neglect, they do not trust others and can become extremely difficult to calm down when stressed, as they feel a loss of control. [3]

X

Trustworthy Source

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Nonprofit organization dedicated to providing and improving psychiatric care for children and adolescents.

Go to source

Children with this disorder can be difficult to work with, but by setting routines, being empathic while disciplining them, and helping them learn about appropriate behavior, you can help a child with RAD understand what to expect and help make the world a less frightening place for them.

Setting Routines and Boundaries

Expect that the child will try to control the situation. A child with RAD has likely had an uncertain, neglect-filled past. For example, the child may not have been fed regularly as an infant, or bounced around from foster care settings so frequently that they never felt secure. As a result, they constantly make attempts to “control” their environment through their behavior. They may manipulate others, rather than genuinely connect with them, because of this need to control. Other controlling behaviors you might see include: Aggressive behavior and outbursts. Clinginess and constant need for attention. Nonstop chattering.

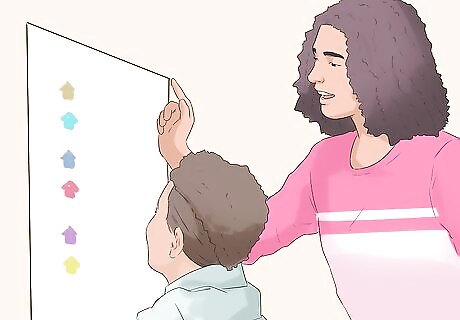

Maintain consistent, predictable schedules and routines. A child with RAD may have not had much consistency as a baby or toddler. It is very important, both from a behavior management standpoint, as well as the child’s own emotional health, that the child know what to expect every day. Creating a routine for a child helps the child feel safe, cared for, and more relaxed. Let the child know the day’s schedule, then stick to it. For example, you could say, “Today you are going to school. After school, we’ll go to the park, then work on homework, then take a bath.” If the child can read, write the day’s schedule in a visible place. You could also draw pictures for a young child. Keep the routine consistent. Kids learn from making sense of patterns in their lives. They’ll understand what is next and understand the behavior expected of them. They will also be less stressed because they know what is coming and how to deal with it. Give the child as much notice as possible if there is going to be a change in the routine. For example, “Next Saturday you’re not going to swimming class as usual, because it is Kyle’s birthday party. We’re going to Kyle’s house instead.” You could get out a calendar and show the child how many days away it is. Do your best to avoid changes in routine with RAD children. It can be too stressful on them and you may notice a backslide in their behavior.

Set expectations and boundaries. Be clear in establishing rules and expectations. Kids with reactive attachment disorder will find loopholes in rule enforcement and may argue with you, so you need to be clear and firm up front. Make the child aware of consequences that will occur if he or she disobeys rules, and follow through with your stated consequences. This can help the child understand that they do have control over certain situations, because they can control their behavior to avoid repercussions. Consider creating a contract with the child that indicates rules, expectations, and consequences for not following the rules. Keep the contract in an easily accessible place for reference. Keep in mind that a contract is a mutual agreement. Let the child have a say in the rules and the consequences to help them take control of their behavior. For example, your contract could say, “Charlie agrees to the following rules: 1) Cleaning his room once a week. 2) No fighting with his brother and sister. 3) Following directions the first time they are given. If Charlie does not follow these rules, he will not be allowed to play video games for 24 hours.” You may also want to specify a reward for following the rules to help provide your child with some positive reinforcement. For example, “If Charlie follows the rules, then he will get to play with his favorite toy.”

Disciplining with Empathy

Communicate the good over the bad. Emphasize the child’s good behavior instead of pointing out the negative. It is important that you maintain the relationship with this child by correcting their behavior in a positive, empathic way. Disciplining a RAD child with harsh words and negative feedback only reinforces their view that they are alone in the world. Say “yes” instead of “no.” For example, the child wants to play outside, but has not yet finished their homework. Say, “Yes, you can go outside as soon as your homework is done!” instead of “No, you need to get your homework done.” Praise rather than scold. Commend what the child did correctly rather than make an issue of what they didn’t do. For example, if the child leaves the door wide open in the middle of winter to rush outside and play in the snow, you might say, “Wow, you did a great job getting all your winter gear on all by yourself! Can you do me a favor and remember to close the door next time? We want our house to stay warm.”

Do your best to remain calm. The child may argue with you, antagonize you, and intentionally get into trouble in order to maintain their control over the situation. Your job as their caregiver is to not engage with their drama. Acknowledge their feelings, but do not fight with them. If the child is having a temper tantrum, for example, you could calmly say, “I understand that you are angry and upset. I will let you work through it so long as you don’t hurt me, or others, or yourself.” Wait until the child has calmed down before talking to them. Stay close to the child to let them know you are there, and restrain them from self-harm or hurting you if necessary, but let the behavior run its course. They are so worked up that talking to them will not accomplish anything.

Use “one-liners” to maintain calm. These are sentences that can prevent power struggles and place responsibility for the child’s behavior on the child. Stay calm and free of sarcasm, and consider using some of the following to diffuse an argument: ”That’s interesting.” ”Hmmmm.” ”I’ll be glad to listen when your voice is as soft as mine.” ”Thanks for the honest answer.”

Avoid timeouts. Timeouts only reinforce the self-isolating behavior of a child with reactive attachment disorder. Instead, you may wish to keep the child with you, talking about what happened and how they could do differently next time. You could say, “I’m so glad you’re sitting here with me. I know it must be hard after what happened. I know you’re upset. But let’s talk about why you’re so upset that you kicked Xavier. What do you think you could do differently next time?”

Let the child know they are loved and safe. Following a tantrum, argument, or bad behavior, reassure the child that you still love/care about them, that you are not going to hurt them, and that they are safe. Children with RAD, as well as neglected children in general, are more attuned to others’ negative emotions than typical children. Tell the child that while you may be upset at the moment, your feelings for the child haven’t changed. For example, you could say, “Emma, I know we were both a little angry before. I want to let you know that I am disappointed in your behavior, but there is nothing you could do that would make me stop loving you. I want to help you make a better choice next time. Let’s talk about how we can fix this together.”

Modeling Appropriate Behavior

Insist on eye contact. A person can’t fully understand emotions without looking at another’s eyes, and it is part of the challenge of a child with RAD to understand emotions, empathy, and develop a conscience. Gentle reminders like, “Mia, eye contact,” or “Can you look me in the eyes when you ask me?” can help nudge the child. Compliment the child for good eye contact. Remember that you don’t want to battle a child with RAD, so if the child seems unwilling or defiant, back off and don’t force it.

Teach the child about their emotions. Consider that a child with RAD has limited understanding of their emotional landscape, and cannot always empathize with others. You can help them learn more about feeling emotions and expressing them appropriately by trying some of the following strategies: Name the emotion you are seeing them express. You could say, “Elijah, you look like you are really angry about this homework assignment! I can see your hands clenched up in fists!” or “You must think that dog is funny. You keep laughing at it!” Help them understand nonverbal language cues like body language or tone of voice. For example, “What do you think it means when someone puts their head in their hands?” Model an appropriate apology when necessary. You could tell the child, “I am sorry I hurt your feelings when I said that you couldn’t wear your red shirt for school pictures. I know it’s your favorite shirt and my saying no made you sad.” Talk about characters in books and TV shows and ask the child what they think the character might be feeling. For example, “How do you think Baby Bear felt when he saw that Goldilocks broke his chair?” If the child doesn’t know, you could say, “I think he probably felt very sad, and maybe a little mad and a little scared because he didn’t know who broke his chair!”

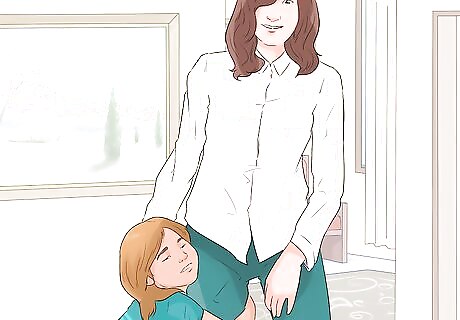

Show physical affection, but be cautious. Most children with reactive attachment disorder do not like to be touched. If you are new to caring for the child, do not jump in right away with a lot of physical contact. Move slowly and establish trust. Do not force them to cuddle or do anything they don’t want to. Rather, give them pats on the back, put an arm around their shoulder, tousle their hair affectionately, or even give them a high-five. Determine their comfort level and work within that, but incorporate physical affection into your daily routine. It helps the child to establish a genuine connection.

Spend quality time with the child. Find something to do that the child enjoys and spend some one-on-one time getting to know them better. You are helping the child understand relationships, as well as learn what a healthy connection feels like. Consider activities like playing board games, reading stories together, going for a hike, or going out for a special treat. Let the child decide the day’s activity. Give them a list of options: “Today we can either do a craft at the library or go fishing at the pond. What sounds better to you?” If you are a teacher, you might show interest in the child by asking about their drawings, spending time with the child while they play with their favorite classroom toy, or saving a special book for them for silent reading time.

Encourage a healthy lifestyle. Maintain your own healthy habits to role model good behavior. Encourage the child to make healthy food choices, get plenty of rest, maintain good hygiene, and exercise. Let the child know that it will be easier to deal with difficult emotions when their body is healthy and strong. Have the child get plenty of exercise. Exercise not only keeps you healthy, but it helps improve depression and keeps you less stressed. Make sure the child is eating a nutritious diet and is getting enough food to meet their needs.

Comments

0 comment