views

Reading Roman Numerals

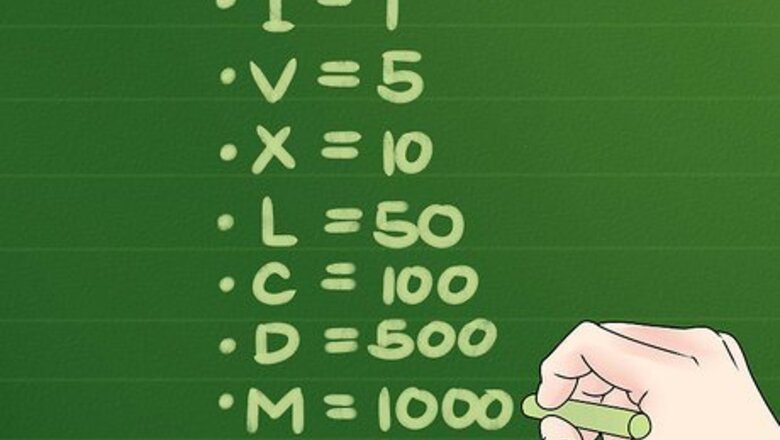

Learn the basic value of each digit. There are only a few Roman numerals, so it doesn't take long to learn them: I = 1 V = 5 X = 10 L = 50 C = 100 D = 500 M = 1000

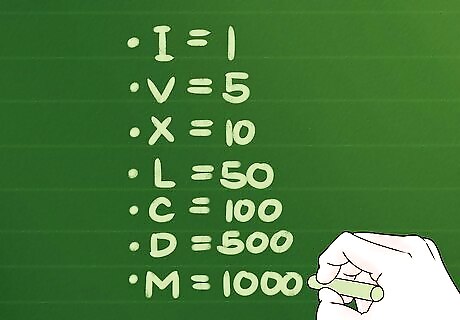

Use a mnemonic. A mnemonic is a phrase that you can memorize more easily than a list of numbers, that will help you remember the order of the digits. Try repeating this one to yourself ten times: I Value Xylophones Like Cows Do Milk.

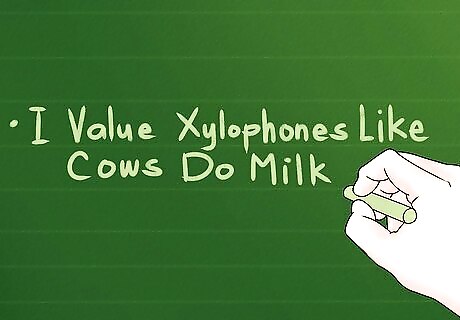

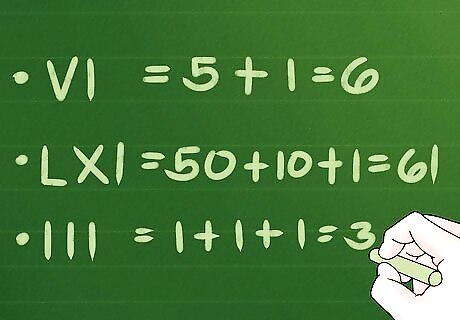

Add numbers with larger digits first. If the digits are ordered largest to smallest, all you need to do to read them is add the value of each digit. Here are some examples: VI = 5 + 1 = 6 LXI = 50 + 10 + 1 = 61 III = 1 + 1 + 1 = 3

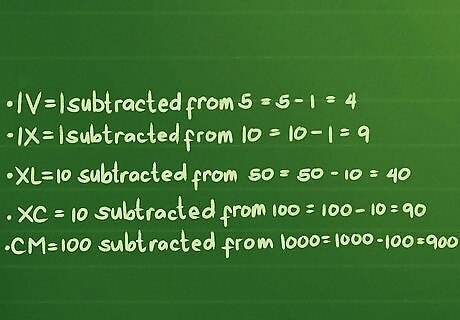

Treat numbers with smaller digits first as subtraction. Most people who use Roman numerals save space by using subtraction to show certain numbers. You'll know this is happening if a smaller digit is in front of a larger digit. This only happens in a few situations: IV = 1 subtracted from 5 = 5 - 1 = 4 IX = 1 subtracted from 10 = 10 - 1 = 9 XL = 10 subtracted from 50 = 50 - 10 = 40 XC = 10 subtracted from 100 = 100 - 10 = 90 CM = 100 subtracted from 1000 = 1000 - 100 = 900

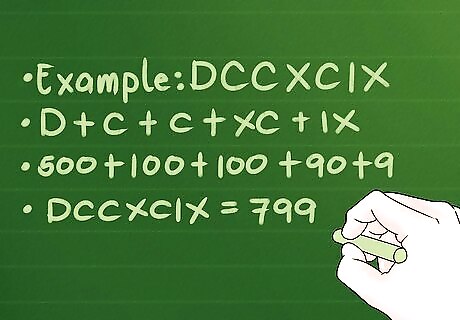

Break a number into parts to understand it. If you need to, divide a number into groups of digits to understand it better. Always make sure you catch any "subtraction problems" with a smaller digit in front of a larger, and include both the digits into the same group. For example, try to read DCCXCIX. There are two places in the number with a small digit in front of a larger one: XC and IX. Keep the "subtraction problems" together and break up the other digits separately: D + C + C + XC + IX. Translate into ordinary numerals using the subtraction rules when necessary: 500 + 100 + 100 + 90 + 9 Add them all together: DCCXCIX = 799.

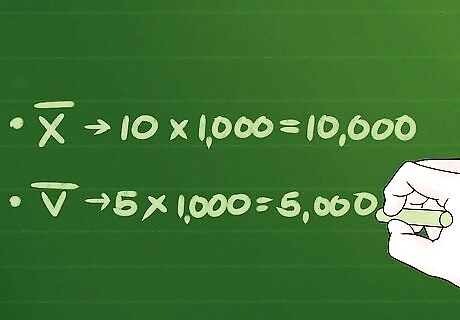

Look for a horizontal bar for very large numbers. If a horizontal line is drawn across the top of a number, multiply the value by 1,000. Be careful, though: many people draw a horizontal line above and below every roman numeral, just as decoration. For example, an X with a "–" written over it means 10,000. If you're not sure whether the bar is just decoration, think about the context. Would a general send in 10 soldiers, or 10,000? Would a recipe use 5 apples, or 5,000?

Examples

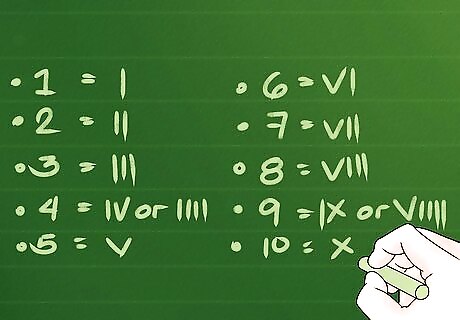

Count from one to ten. This is a good set of numbers to learn. If there are two options listed, there are two correct ways to write that number. Most people stick to one or the other, either using the subtraction method when possible, or writing everything as addition. 1 = I 2 = II 3 = III 4 = IV or IIII 5 = V 6 = VI 7 = VII 8 = VIII 9 = IX or VIIII 10 = X

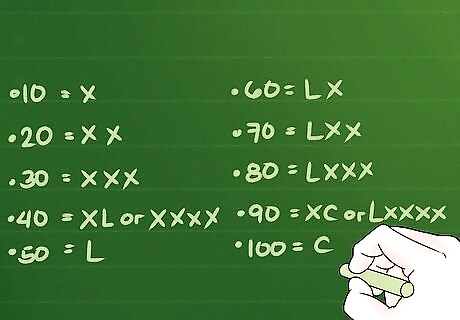

Count by tens. Here are the Roman numerals from ten to hundred, counting by tens: 10 = X 20 = XX 30 = XXX 40 = XL or XXXX 50 = L 60 = LX 70 = LXX 80 = LXXX 90 = XC or LXXXX 100 = C

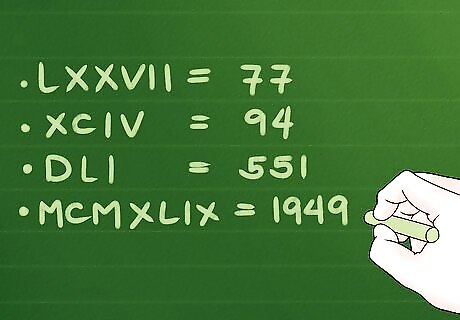

Challenge yourself with more difficult numbers. Here are some more difficult challenges. Try to get them yourself, then highlight the answer to make it visible: LXXVII = 77 XCIV = 94 DLI = 551 MCMXLIX = 1949

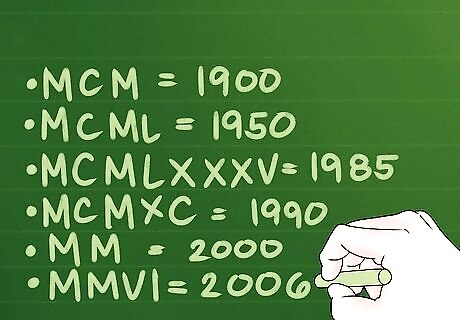

Read dates. Next time you watch a movie, look for a date in Roman numerals during the opening film credits. You can break them down into parts to make them easier to read: MCM = 1900 MCM L = 1950 MCM LXXX V = 1985 MCM XC = 1990 MM = 2000 MM VI = 2006

Reading Unusual Old Texts

Use this section only for old text. Roman numerals were not standardized until modern times. Even the Romans themselves used them inconsistently, and all sorts of variations were used into medieval times and even the 19th and early 20th centuries. If you come across an old text with numerals that don't make sense in the usual system, refer to the steps below for help interpreting it. If you're learning Roman numerals for the first time, ignore this section.

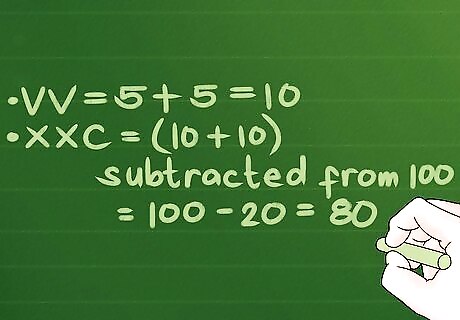

Read unusual repetitions. Most modern users don't like to repeat the same digit if they can avoid it, and never subtracted more than one digit at a time. Old sources didn't obey these rules, but it's usually easy to figure out what they meant. For example: VV = 5 + 5 = 10 XXC = (10 + 10) subtracted from 100 = 100 - 20 = 80

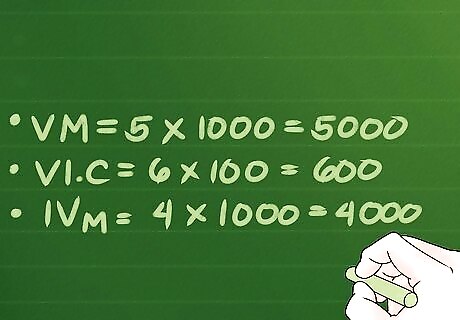

Look for signs of multiplication. Confusingly, old texts sometimes use the smaller digit in front of the larger to mean multiplication, not subtraction. For example, VM might mean 5 x 1000 = 5000. There's not always an easy way to tell when this is happening, but sometimes the number is slightly altered: A period between the two numbers: VI.C = 6 x 100 = 600. A subscript: IVM = 4 x 1000 = 4000.

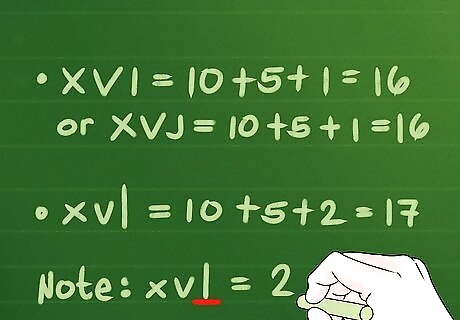

Understand variations of I. In old printed works, the symbol j or J is sometimes used instead of i or I at the end of a number. More rarely, an extra tall I at the end of a word can signify 2 instead of 1. For example, xvi or XVJ, both equal 16. xvI = 10 + 5 + 2 = 17

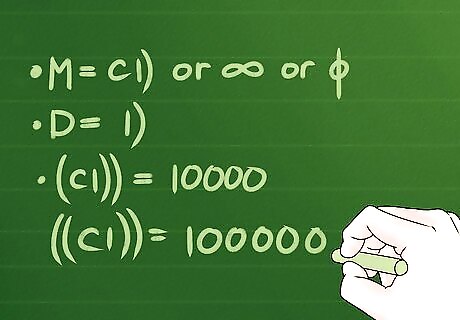

Read large numbers with unusual symbols. Early printers sometimes used a symbol called the apostrophus, similar to a backwards C or a ) symbol. This and variations of it were only used for large numbers: M was sometimes written as CI) or ∞ by early printers, or as a ϕ in ancient Rome. D was sometimes written as I) Enclosing the above numbers inside additional ( and ) symbols meant multiplication by ten. For example, (CI)) = 10,000 and ((CI))) = 100,000.

Comments

0 comment