views

Rationalizing a Monomial Denominator

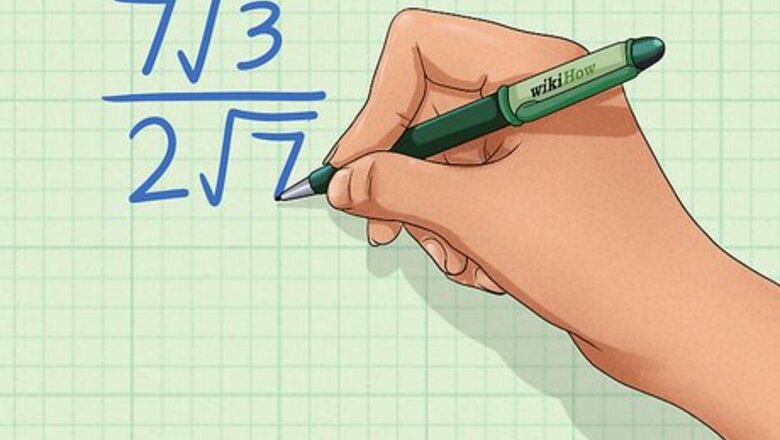

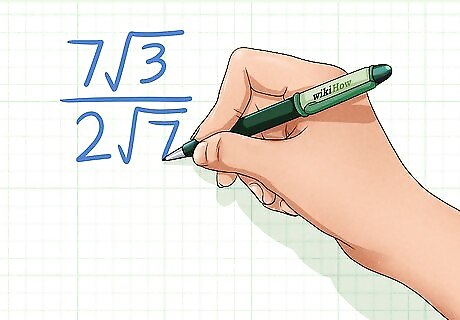

Examine the fraction. A fraction is written correctly when there is no radical in the denominator. If the denominator contains a square root or other radical, you must multiply both the top and bottom by a number that can get rid of that radical. Note that the numerator can contain a radical. Don't worry about the numerator. 7 3 2 7 {\displaystyle {\frac {7{\sqrt {3}}}{2{\sqrt {7}}}}} {\frac {7{\sqrt {3}}}{2{\sqrt {7}}}} We can see that there is a 7 {\displaystyle {\sqrt {7}}} {\sqrt {7}} in the denominator.

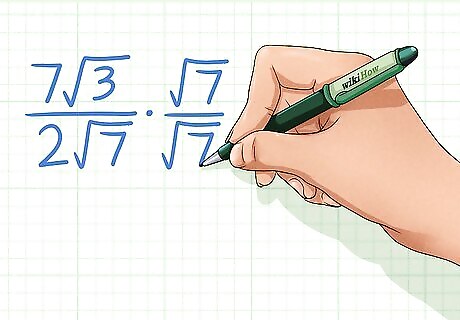

Multiply the numerator and denominator by the radical in the denominator. A fraction with a monomial term in the denominator is the easiest to rationalize. Both the top and bottom of the fraction must be multiplied by the same term, because what you are really doing is multiplying by 1. 7 3 2 7 ⋅ 7 7 {\displaystyle {\frac {7{\sqrt {3}}}{2{\sqrt {7}}}}\cdot {\frac {\sqrt {7}}{\sqrt {7}}}} {\frac {7{\sqrt {3}}}{2{\sqrt {7}}}}\cdot {\frac {{\sqrt {7}}}{{\sqrt {7}}}}

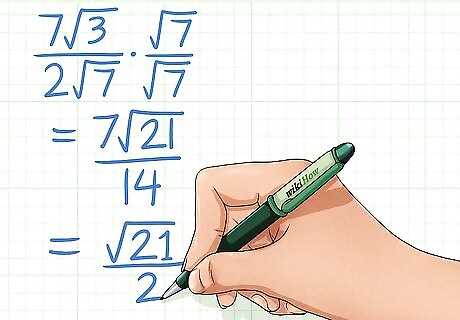

Simplify as needed. The fraction has now been rationalized. 7 3 2 7 ⋅ 7 7 = 7 21 14 = 21 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {7{\sqrt {3}}}{2{\sqrt {7}}}}\cdot {\frac {\sqrt {7}}{\sqrt {7}}}={\frac {7{\sqrt {21}}}{14}}={\frac {\sqrt {21}}{2}}} {\frac {7{\sqrt {3}}}{2{\sqrt {7}}}}\cdot {\frac {{\sqrt {7}}}{{\sqrt {7}}}}={\frac {7{\sqrt {21}}}{14}}={\frac {{\sqrt {21}}}{2}}

Rationalizing a Binomial Denominator

Examine the fraction. If your fraction contains a sum of two terms in the denominator, at least one of which is irrational, then you cannot multiply the fraction by it in the numerator and denominator. 4 2 + 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}} {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}} To see why this is the case, write an arbitrary fraction 1 a + b , {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{a+b}},} {\frac {1}{a+b}}, where a {\displaystyle a} a and b {\displaystyle b} b are irrational. Then the expression ( a + b ) ( a + b ) = a 2 + 2 a b + b 2 {\displaystyle (a+b)(a+b)=a^{2}+2ab+b^{2}} (a+b)(a+b)=a^{{2}}+2ab+b^{{2}} contains a cross-term 2 a b . {\displaystyle 2ab.} 2ab. If at least one of a {\displaystyle a} a and b {\displaystyle b} b is irrational, then the cross-term will contain a radical. Let's see how this works with our example. 4 2 + 2 ⋅ 2 + 2 2 + 2 = 4 ( 2 + 2 ) 4 + 4 2 + 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}\cdot {\frac {2+{\sqrt {2}}}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}={\frac {4(2+{\sqrt {2}})}{4+4{\sqrt {2}}+2}}} {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}\cdot {\frac {2+{\sqrt {2}}}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}={\frac {4(2+{\sqrt {2}})}{4+4{\sqrt {2}}+2}} As you can see, there's no way we can get rid of the 4 2 {\displaystyle 4{\sqrt {2}}} 4{\sqrt {2}} in the denominator after doing this.

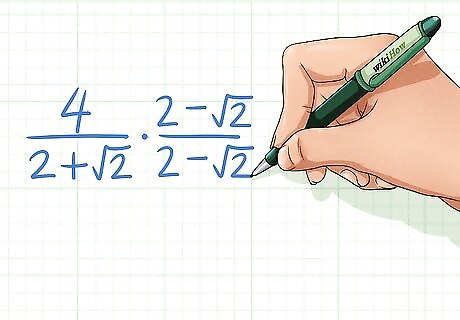

Multiply the fraction by the conjugate of the denominator. The conjugate of an expression is the same expression with the sign reversed. For example, the conjugate of 2 + 2 {\displaystyle 2+{\sqrt {2}}} 2+{\sqrt {2}} is 2 − 2 . {\displaystyle 2-{\sqrt {2}}.} 2-{\sqrt {2}}. 4 2 + 2 ⋅ 2 − 2 2 − 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}\cdot {\frac {2-{\sqrt {2}}}{2-{\sqrt {2}}}}} {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}\cdot {\frac {2-{\sqrt {2}}}{2-{\sqrt {2}}}} Why does the conjugate work? Going back to our arbitrary fraction 1 a + b , {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{a+b}},} {\frac {1}{a+b}}, multiplying by the conjugate in the numerator and denominator results in the denominator being ( a + b ) ( a − b ) = a 2 − b 2 . {\displaystyle (a+b)(a-b)=a^{2}-b^{2}.} (a+b)(a-b)=a^{{2}}-b^{{2}}. The key here is that there are no cross-terms. Since both of these terms are being squared, any square roots will be eliminated.

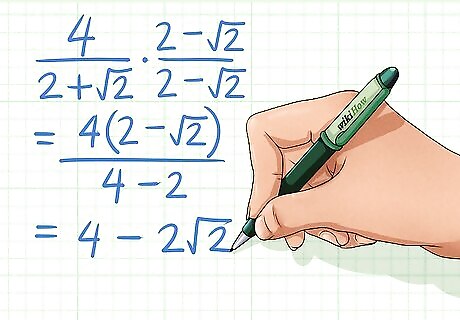

Simplify as needed. 4 2 + 2 ⋅ 2 − 2 2 − 2 = 4 ( 2 − 2 ) 4 − 2 = 4 − 2 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}\cdot {\frac {2-{\sqrt {2}}}{2-{\sqrt {2}}}}={\frac {4(2-{\sqrt {2}})}{4-2}}=4-2{\sqrt {2}}} {\frac {4}{2+{\sqrt {2}}}}\cdot {\frac {2-{\sqrt {2}}}{2-{\sqrt {2}}}}={\frac {4(2-{\sqrt {2}})}{4-2}}=4-2{\sqrt {2}}

Working with Reciprocals

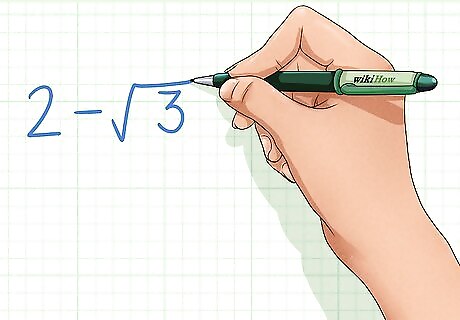

Examine the problem. If you are asked to write the reciprocal of a set of terms containing a radical, you will need to rationalize before simplifying. Use the method for monomial or binomial denominators, depending on whichever applies to the problem. 2 − 3 {\displaystyle 2-{\sqrt {3}}} 2-{\sqrt {3}}

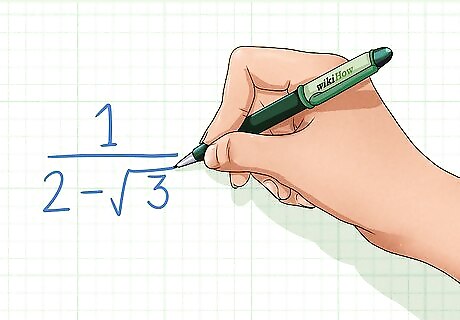

Write the reciprocal as it would usually appear. A reciprocal is created when you invert the fraction. Our expression 2 − 3 {\displaystyle 2-{\sqrt {3}}} 2-{\sqrt {3}} is actually a fraction. It's just being divided by 1. 1 2 − 3 {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2-{\sqrt {3}}}}} {\frac {1}{2-{\sqrt {3}}}}

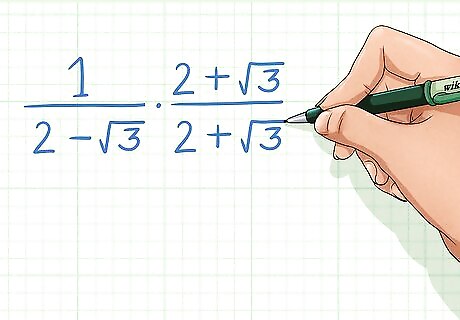

Multiply by something that can get rid of the radical on the bottom. Remember, you're actually multiplying by 1, so you have to multiply both the numerator and denominator. Our example is a binomial, so multiply the top and bottom by the conjugate. 1 2 − 3 ⋅ 2 + 3 2 + 3 {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2-{\sqrt {3}}}}\cdot {\frac {2+{\sqrt {3}}}{2+{\sqrt {3}}}}} {\frac {1}{2-{\sqrt {3}}}}\cdot {\frac {2+{\sqrt {3}}}{2+{\sqrt {3}}}}

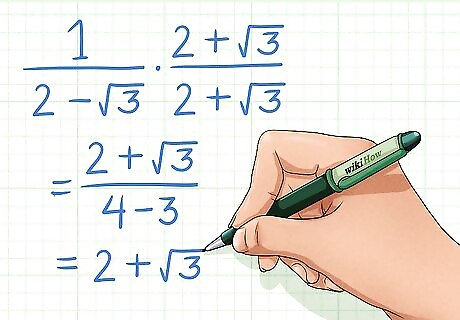

Simplify as needed. 1 2 − 3 ⋅ 2 + 3 2 + 3 = 2 + 3 4 − 3 = 2 + 3 {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{2-{\sqrt {3}}}}\cdot {\frac {2+{\sqrt {3}}}{2+{\sqrt {3}}}}={\frac {2+{\sqrt {3}}}{4-3}}=2+{\sqrt {3}}} {\frac {1}{2-{\sqrt {3}}}}\cdot {\frac {2+{\sqrt {3}}}{2+{\sqrt {3}}}}={\frac {2+{\sqrt {3}}}{4-3}}=2+{\sqrt {3}} Do not be thrown off by the fact that the reciprocal is the conjugate. This is just a coincidence.

Rationalizing Denominators with a Cube Root

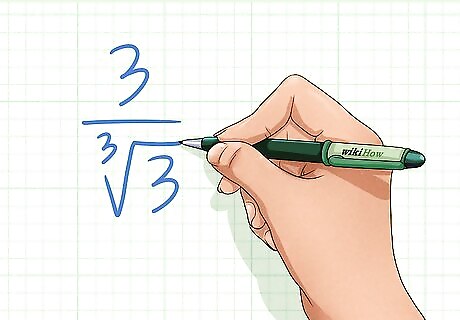

Examine the fraction. You can also expect to face cube roots in the denominator at some point, though they are rarer. This method also generalizes to roots of any index. 3 3 3 {\displaystyle {\frac {3}{\sqrt[{3}]{3}}}} {\frac {3}{{\sqrt[ {3}]{3}}}}

Rewrite the denominator in terms of exponents. Finding an expression that will rationalize the denominator here will be a bit different because we cannot simply multiply by the radical. 3 3 1 / 3 {\displaystyle {\frac {3}{3^{1/3}}}} {\frac {3}{3^{{1/3}}}}

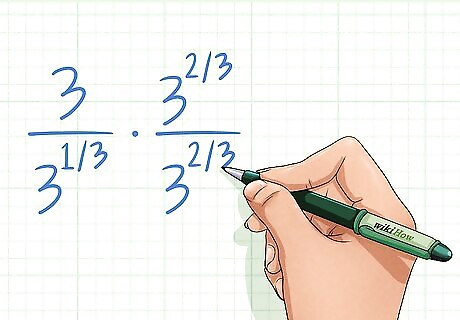

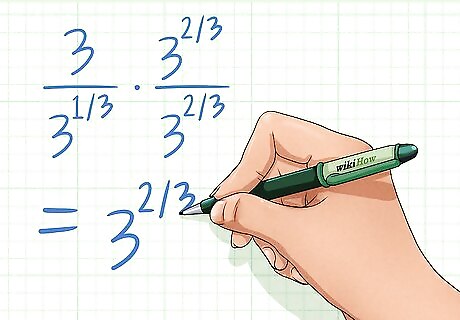

Multiply the top and bottom by something that makes the exponent in the denominator 1. In our case, we are dealing with a cube root, so multiply by 3 2 / 3 3 2 / 3 . {\displaystyle {\frac {3^{2/3}}{3^{2/3}}}.} {\frac {3^{{2/3}}}{3^{{2/3}}}}. Remember that exponents turn a multiplication problem into an addition problem by the property a b a c = a b + c . {\displaystyle a^{b}a^{c}=a^{b+c}.} a^{{b}}a^{{c}}=a^{{b+c}}. 3 3 1 / 3 ⋅ 3 2 / 3 3 2 / 3 {\displaystyle {\frac {3}{3^{1/3}}}\cdot {\frac {3^{2/3}}{3^{2/3}}}} {\frac {3}{3^{{1/3}}}}\cdot {\frac {3^{{2/3}}}{3^{{2/3}}}} This can generalize to nth roots in the denominator. If we have 1 a 1 / n , {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{a^{1/n}}},} {\frac {1}{a^{{1/n}}}}, we multiply the top and bottom by a 1 − 1 n . {\displaystyle a^{1-{\frac {1}{n}}}.} a^{{1-{\frac {1}{n}}}}. This will make the exponent in the denominator 1.

Simplify as needed. 3 3 1 / 3 ⋅ 3 2 / 3 3 2 / 3 = 3 2 / 3 {\displaystyle {\frac {3}{3^{1/3}}}\cdot {\frac {3^{2/3}}{3^{2/3}}}=3^{2/3}} {\frac {3}{3^{{1/3}}}}\cdot {\frac {3^{{2/3}}}{3^{{2/3}}}}=3^{{2/3}} If you need to write it in radical form, factor out the 1 / 3. {\displaystyle 1/3.} 1/3. 3 2 / 3 = ( 3 2 ) 1 / 3 = 9 3 {\displaystyle 3^{2/3}=(3^{2})^{1/3}={\sqrt[{3}]{9}}} 3^{{2/3}}=(3^{{2}})^{{1/3}}={\sqrt[ {3}]{9}}

Comments

0 comment