views

Drawing Inspiration from the Story

Draw inspiration from a key theme of the story. A successful title should fit the story in an apt but evocative way. Think about the major theme of your story--is it revenge? grief? alienation?--and think of titles that evoke that theme. If, for example, the theme is redemption, you might title your story something like “Falling into Grace.”

Name the title after an important setting. If one particular setting plays a central role in the story, consider using that setting for your title. For example, if the crux of your story is something that happened in a town called Washington Depot, you might simply title the story “Washington Depot.” Or you might draw inspiration from events that happen there title the story something like “The Wraiths of Washington Depot” or “Washington Depot in Flames.”

Choose a title inspired by a pivotal event in the story. If there’s a particular event that either predominates the story or plays a key role in setting events in motion, consider using that as your title inspiration. For example, you might devise something like, “What Happened in the Morning” or “A Death Among Thieves.”

Base the title on your book’s main character. Naming the book after an important character can provide a kind of compelling simplicity to a title. It helps, though, if the character’s name is something notable or memorable. A number of venerated authors have gone this route: Charles Dickens with David Copperfield and Oliver Twist, Charlotte Bronte with Jane Eyre, and Miguel de Cervantes with Don Quixote.

Name the title after a memorable line in the story. If you have a particularly clever or original turn of phrase in your story that captures an important element or theme, use it or a version of it for your title. For example, novels like To Kill a Mockingbird, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, and Sleepless in Seattle are all based on lines from the stories themselves.

Drawing Inspiration from Elsewhere

Research. Take inventory of the key elements of your story, particularly objects and places. Research those places and objects and look for title inspiration. For example, if your story centers on an emerald passed down through generations of the same family, you might research emeralds and find that they’ve traditionally been associated with faith and hope. So you might title your story something like “The Rock of Hope.”

Check out your own bookshelves. Look over the book titles on your own shelves and note down the titles that jump out at you. Write down both the titles that jump out to you now and the books whose titles alone drew you in. Review your list and try to determine what the successful titles have in common. For example, do they appeal to the senses, appeal to the reader’s imagination, etc?

Use an allusion. An allusion is a reference to or a phrase taken from an external source like another literary work, a song, or even something as commonplace as a brand or slogan. Many authors have taken inspiration from classic works, including William Faulkner, whose Sound and the Fury is inspired by a line in Macbeth, and John Steinbeck, whose Grapes of Wrath is an allusion to a line in “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Other authors have drawn inspiration from local vernacular sayings, like the London Cockney saying “queer as a clockwork orange” that inspired Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. Still others have used allusions to popular culture, like Kurt Vonnegut, who used the Wheaties slogan for his book Breakfast of Champions.

Avoiding Common Mistakes

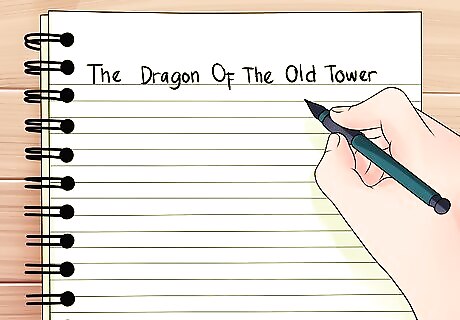

Create a genre-appropriate title. If you choose a title that sounds like it belongs in one genre while the actual content of the story belongs in another, you’ll not only confuse potential readers, you may alienate them. For example, if your title sounds distinctly fantasy-esque, like “The Dragon of the Old Tower,” but the story is in fact about modern-day brokers on Wall Street, you’ll alienate those who pick up your story looking for fantasy and you’ll miss entirely those looking for a story about something modern or about the world of elite finance, etc.

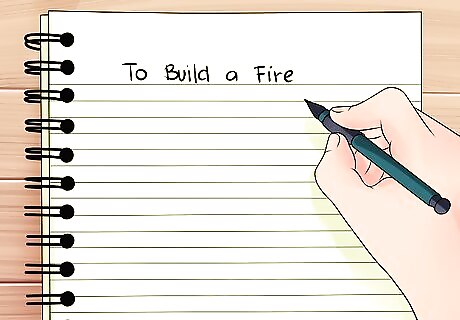

Limit the length. In the majority of cases, titles that are brief but impactful are more successful than those that are long and difficult to remember. Ask yourself, “If I could summarize my story in one word or phrase, what would it be?” For example, “A Man Discovers the Perils of a Solo Trek Through the Yukon” is likely less compelling to potential readers than “To Build a Fire,” which is shorter and more imaginative.

Make it interesting. Titles that use poetic language, vivid imagery, or a bit of mystery tend to be alluring to potential readers. Poetic language in a title, like “A Rose for Emily” or Gone with the Wind, draws readers with an elegant turn of phrase that promises an equally poetic story or writing style. Titles that evoke vivid imagery appeal to readers because they conjure something tangible and meaningful. A title like Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, though long, creates an immediate and vivid image that conjures an idea of a battle between good and evil. Imbuing your title with a bit of mystery can also draw readers in. A title like Something Wicked This Way Comes (also an allusion from Macbeth) or “The Black Cat” give just enough information to raise questions that will pull the reader into the story.

Use alliteration sparingly and with caution. Though alliteration--the repetition of successive sounds at the beginning of words--can make a title catchier or more memorable, it can also make it sound trite or hokey if not done well. Subtle alliteration, like I Capture the Castle or The Count of Monte Cristo, can add appeal to a title. Obvious or forced alliteration, on the other hand--like "The Guileless Guide of Gullible Gus" or "The Especially Exciting Endeavors of Elanor Ellis"--can easily dissuade a potential reader from picking up your story.

Comments

0 comment