views

X

Research source

Designing Pilot Study Protocol

Identify the larger idea or project your pilot study is based on. Ideally, if your pilot study is successful, it will lead to a much larger study with a more expansive scope and extensive budget. In your pilot study protocol, describe how the pilot study will pave the way for that larger study to become a reality. Ideally, you've already planned the methodology for the full study. Then, you can use the pilot study to assess how doable that methodology actually is.

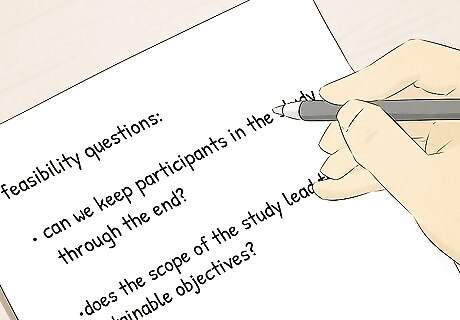

List the feasibility questions you plan to answer with your pilot study. Generally, you're using a pilot study to determine if you can actually do the full study (assuming you have appropriate funds and resources available). Look at the planned methodology for the full study and focus on the things you're not sure will work. These are the questions you need to ask. The objective of your pilot study is to answer those questions. For example, if your study will take several months to complete, you might wonder if you'll be able to retain participants through to the end. Your feasibility question would be something like, "Can we keep participants in the study through the end?"

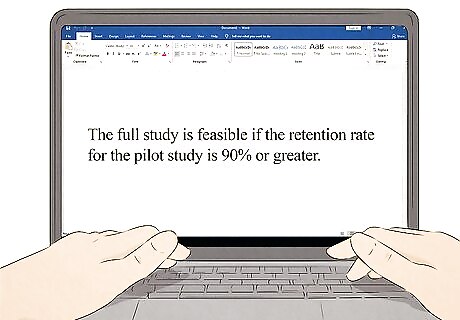

Provide a concrete measure to determine feasibility. Once you've stated the questions your pilot study plans to evaluate, describe how you'll answer those questions. A quantifiable measure enables you to make an objective determination if your full study is feasible based on the pilot study. For example, if you're concerned about whether your participants will stick it out through a long-term study, you might write: "The full study is feasible if the retention rate for the pilot study is 90% or greater." You might have multiple criteria that you're evaluating through the pilot study. If so, list each of these separately along with a concrete measure for determining the feasibility of the full study.

Calculate your sample size for the pilot study. You often don't have to do formal sample size calculations for a pilot study. However, you do need to have enough participants that your observations will be useful. Generally, include 10-20% of the number of participants planned for your full study. The objective of the pilot study isn't necessarily to predict anything about the outcome of the full study, so you don't have to worry about your sample size being too small to generalize to the larger population. Keep in mind the money and resources you have available when you determine the sample size for your pilot study. You want to keep the sample size within your means to basically do everything on your own locally, since you're unlikely to have access to money for travel or professional services.

Running the Pilot

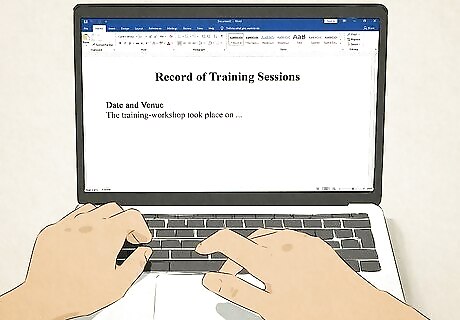

Document training of other researchers working on the pilot. If you bring in other researchers to work with you on your pilot study, create a detailed record of their training sessions, including the materials they're provided and the instructions they're given. This record enables you to correct any errors in training before the full study. For example, if you have randomization procedures to control bias in the study, your researchers need to understand how to implement those procedures. If your instructions are confusing, your study could end up being biased. Plan on keeping the pilot researchers with you for the full study. They can help train any additional researchers you bring on board.

Recruit participants that cover the entire range of your full study. Follow the same recruiting methods you've outlined for your full study to recruit the same types of people. Covering the full range enables you to more easily project that the results of the pilot study will be replicated by the full study. For example, if your full study will include participants in 3 age groups ranging from 18 to 52, your pilot study would ideally include participants from each of the 3 age groups you've delineated for the full study. It might turn out that your recruiting methods work for one of the age groups but aren't as effective for the others. Similarly, you might find that one age group is more likely to stay through the whole study than others. Evaluate how difficult it is to recruit participants and how long it takes for you to recruit the number of participants you need. You can scale this to determine if the recruiting methods you used will work for the full study or if it would take too long for you to get enough participants on board.

Use methods as rigorous as those in the full study. Using the same methodology as you intend to use for the full study allows you to evaluate whether you can do the full study. If, on the other hand, you take short cuts in the pilot study, you won't have any usable information that you can apply to the full study. For example, if your full study will be double-blind, your pilot should also have double-blind procedures in place. While this might make your pilot a little more expensive, it's the only way to accurately test the feasibility of the full study. If you're trying to figure out if you'll retain participants throughout the course of the full study, the pilot study should take just as long as the full study is planned to take.

Implementing Your Findings

Interview participants about their experience in the pilot study. Talking to the participants after the pilot study is over gives you valuable information about your methodology. Participants can point out issues that you might've overlooked if you only considered things from a researcher's perspective. For example, if you had a pilot study to determine if you could retain participants through the end of the study, you might give exit interviews with participants who left the study to find out why they left. You could then use that information to adjust the full study for greater retention of participants. In addition to formal interviews after the study, you or other researchers working with you can ask participants questions during the study and encourage them to speak up when they have a problem or if there's something they don't understand. Instructions or questions that might seem clear to you can be confusing for participants. Talking to participants about their experience can help you identify areas where your instructions or questions could be clarified.

Modify the full study's methodology based on the pilot study. The findings from your pilot study tell you whether the methodology you originally planned for the full study is feasible. If the methods didn't work in the pilot study, they likely won't work for the full study unless they're changed. For example, if your question was retention of participants and fewer than half of your participants stayed through the end of the pilot study, you would need to modify the full study to make it more likely for participants to stay. You could also expand the full study to include more participants with the understanding that at least half of them would drop out. Information you gained from the pilot study may require you to completely redesign your methodology for the full study. If you change the methodology to a significant extent, you may need a second pilot study to evaluate the revised methodology.

Incorporate your results into the full study if you didn't find any problems. Sometimes, a pilot study reveals that the methodology for your full study is sound and workable. If you don't have to change anything about the protocol for the full study, the pilot study simply gives you a jump-start on the full study. If your pilot study sample didn't cover the entire range anticipated for your full study, you'll need to adjust your full study sample to correct for the bias in your pilot study sample. Otherwise, your final results will be skewed.

Comments

0 comment