views

Guantánamo Bay (Cuba): It started out as questioning about CIA policy, contracts and cables. Then it shifted to a more visceral examination of what happened to the men accused of conspiring in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks while they were held in secret prisons, with a former interrogator testifying about chains, shackles, hoods and threats to kill one prisoner’s son.

In a pre-trial hearing on Tuesday, David Nevin, the lawyer for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the accused mastermind of the 9/11 plot, held up various pieces of evidence collected at one of the CIA’s now-closed overseas detention and interrogation sites. He asked the witness, James E. Mitchell, a former CIA contract psychologist who worked in the secret prisons and helped devise the torture program, what they were.

Shown a chain with a red lock and built-in blue metal device, Mitchell said it looked like something you could “cinch up like a horse collar” but declared the device “completely unfamiliar to me.”

His answers were much the same as he was confronted with questions about other accounts of how the prisoners were treated. Mitchell said he did not recognize a screeching rendition of the heavy metal song “Let the Bodies Hit the Floor,” which detainees claimed was blasted at them in isolation. He disputed the fictional portrayal in the recent film “The Report” of Mohammed being violently water-boarded.

Mohammed “didn’t scream, grunt or do anything,” Mitchell said, citing his recollection of the 183 times he water-boarded him in March 2003. Nevin responded to Mitchell’s account by reading from a CIA cable that described Mohammed letting out a “whimper, whine and moan” as guards led him to the water-board.

It was the sixth day of testimony by Mitchell in a pre-trial hearing focused on the torture of the defendants during their three and four years of CIA captivity, before they were sent to the military prison at Guantánamo Bay.

For much of last week, lawyers questioned Mitchell about documents, intelligence and alphanumeric codes used to mask the identities of people who worked at the black sites and obscure the locations of the prisons.

But the tone changed dramatically on Monday, when Mitchell testified that he threatened to kill one of Mohammed’s sons if there was another attack on America.

He said he did so after he consulted a lawyer at the agency’s Counterterrorism Center about how to make the threat without violating the Torture Convention.

He said he was advised to make the threat conditional.

So, before telling Mohammed “I will cut your son’s throat,” Mitchell said, he added a series of caveats. They included “if there was another catastrophic attack in the United States,” if Mohammed withheld “information that could have stopped it” and “if another American child was killed.”

Mitchell said he made the threat in March 2003 as “an emotional flag” as he was transitioning from waterboarding and other violent “enhanced interrogation techniques” to more traditional questioning of Mohammed.

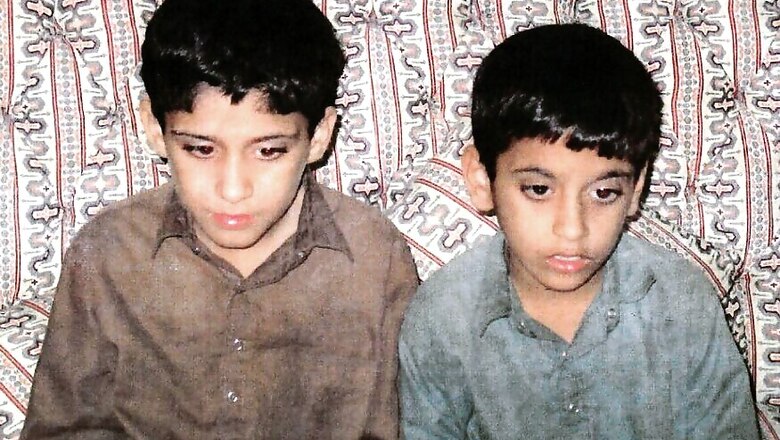

Pakistani security forces reportedly seized Mohammed’s sons, Abed, 7, and Yusuf, 9, in September 2002 in a joint raid with U.S. forces that apprehended Ramzi bin al-Shibh, another defendant in the 9/11 war crimes case. Mohammed would be captured in Pakistan six months later. He was at a CIA black site in Poland later that month when Mitchell made the threat.

The boys were subsequently released and are believed to be living in Iran with their mother, but Mohammed apparently did not know their fate until many years later, after his transfer to Guantánamo Bay in 2006.

It was one of the most emotional moments in the testimony by Mitchell on the question of torture to help the judge decide what evidence will be allowed at the death-penalty trial, which is scheduled to start next year.

Mitchell was unapologetic.

He said that eight children died in the 9/11 hijackings that killed 2,976 people in New York, in Pennsylvania and at the Pentagon. Then he gestured toward Mohammed, who was sitting with his lawyers 25 feet away and declared, “He’s smirking.”

The smirk, or any emotion, was not visible from a spectator’s gallery at the back of the court. Mohammed appeared impassive throughout the testimony, occasionally fingering his long, orange-dyed beard, while his lawyer questioned Mitchell.

“Do you think that telling someone that might instill fear in that person?” Nevin asked.

“Yes, I do,” Mitchell replied. “That was the only time that I made that threat to him.”

Mitchell said he also invoked Mohammed’s children during interrogations again that same month, March 2003, in pressing for details on the whereabouts of Mohammed’s nephew, Ammar al-Baluchi. Mitchell quoted himself as telling Mohammed that it would be “safer” for his family if he helped the United States find al-Baluchi rather than “have him running around and the U.S. dropping a missile on him.”

Al-Baluchi, who is charged in the same case with helping the 9/11 hijackers with money transfers and travel arrangements, was captured in Pakistan in April 2003 in a vehicle with another defendant in the case, Walid bin Attash.

Zeke Johnson, a program director for Amnesty International who was watching the proceedings, said the threat to kill one of Mohammed’s children no doubt broke the law.

“Threatening to kill a detainee’s child would violate the Convention Against Torture and be illegal,” Johnson said. “Anyone who broke the law must be held accountable — from those at the top who ordered it to those who carried it out.”

Carol Rosenberg c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment