views

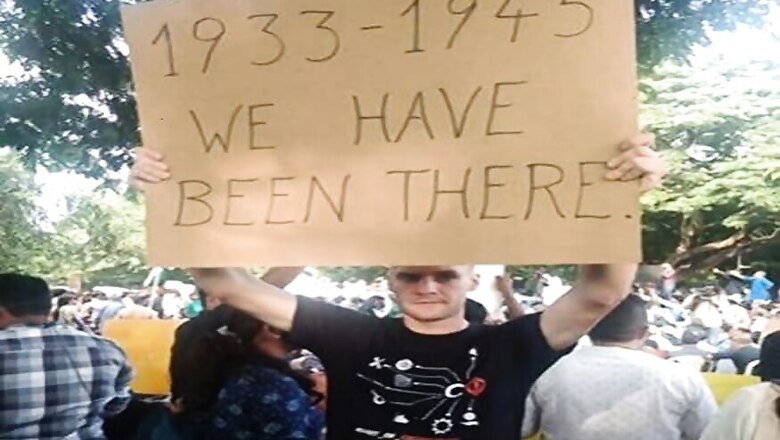

Who is Janne-Mette Johansson? Till recently, few knew about the tourist from Norway. But last month, she turned into a symbol of resistance against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA); courtesy, the ham-fisted approach of some hotheads in the ruling dispensation.

Three days after Johansson, who is in her early seventies, participated in a protest march, the Foreigners Regional Registration Office in Kochi summoned her and questioned her involvement in the march in the city. The Norwegian woman, who arrived in India in October, had a tourist visa. She later told the media that she had been asked to leave “at once”.

Now tourists are supposed to enjoy their visit to the country they are visiting; they are not supposed to take up causes impinging upon the politics of their host country. Besides, the fundamental rights that our constitution guarantees are for citizens, not visitors. So, technically, Johansson can’t claim that her rights have been violated.

But great democracies are not run just by technicalities. Congress leader Shashi Tharoor participates in a debate at the Oxford Union Society and accuses the British for all the ills India suffers from. He follows that up with a book criticising the Raj for real and imaginary sins. Even Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leaders and supporters laud him for that. Film star Priyanka Chopra goes to the United States and makes snide remarks about President Donald Trump’s policies. She receives applause, especially from the liberals.

But an unknown tourist joins hands with protesters against the CAA, and she is asked to leave. If Tharoor was not slammed by the British government and Chopra was not deported, why are our leaders so tetchy? Days before Johansson was ordered to go back, a German student from IIT Madras, Jakob Lindenthal, was also asked to leave for the same reason.

Our government doesn’t seem to like anybody disagreeing with it. British-born writer Aatish Ali Taseer wrote against Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Time magazine in May. Then, the ministry of home affairs (MEA) revoked his Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) card. The official reason given was that he concealed the nationality of his late father, who was a Pakistani citizen.

Even if the revocation was technically sound, the timing—it was done a few months after his anti-Modi write-up—raised many an eyebrow. As many as 250 literary luminaries and media personalities, including Nobel Prize winners Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk and John Coetzee, slammed the move. They alleged that Taseer “appears to have been targeted for an extremely personal form of retaliation”. The signatories included Salman Rushdie and Amitav Ghosh.

“Denying access to the country to writers of both foreign and Indian origin casts a chill on public discourse,” said the letter which was published by the free speech platform PEN America. “It flies in the face of India’s traditions of free and open debate and respect for a diversity of views, and weakens its credentials as a strong and thriving democracy.”

Five years ago, the government had disallowed Greenpeace India campaigner Priya Pillai from boarding her flight to London at the Indira Gandhi International Airport in New Delhi. She was going to London to address British parliamentarians on the rights of forest communities in India which, according to Greenpeace, were “being infringed for coal mining”.

If the objective of the punitive action was to stop her from maligning the image of India in the world, it failed miserably. Indeed, it assisted her to do that in a much more vigorous, and apparently creditable, manner. In a statement issued by Greenpeace, Pillai said, “I am shocked and saddened the government has yet again run roughshod over people working to protect democratic rights in the country.”

Had Pillai been allowed to go to London to meet a subcommittee of the British MPs, there would have been no news—certainly not in India’s newspapers and news channels. Even in the British newspapers, there would have been, if at all, a brief item. By stopping her going there, the unknown activist became a national celebrity—and the issue became international.

UK MP Virendra Sharma, a member of the committee before which Pillai was to make a presentation, castigated the Indian officials who had stopped her boarding the plane. “The alleged detention of Priya Pillai is a worrying development. Priya had been invited to address our ‘All Party Parliamentary Group’… Democracy requires freedom of campaign, and freedom to question the government,” he said.

Pillai’s views, and those of her ilk, were aired prominently all over. The offloading exercise was a comprehensive failure: it was bad in law, as evident from the adverse reactions the government had to face from courts; it was bad in principle as it violated the fundamental right to express one’s views; and it was self-defeating, for the strong-arm tactics could not stop Pillai from expressing her views. Worse, the sledgehammer approach bestowed a verisimilitude of veracity upon the patently discredited views of activists.

Similarly, the actions against Johansson and Taseer have been self-defeating, for the targets have been lionised.

Now the prime minister of India could not be aware of the activities of Johansson, the flaws in Taseer’s papers, or the travel plans of Pillai. Evidently, there are people in the system who keep track of such things. It hasn’t occurred to them that they are doing great harm to the leader they are ostensibly helping.

It seems that Narendra Modi is surrounded by friends, advisers, courtiers and, most alarmingly, bhaktas, who are always eager to exhibit their loyalty to him. The PM may find a Voltaire quote instructive: “May God defend me from my friends: I can defend myself from my enemies.”

(The author is a freelance journalist. Views expressed are personal)

Comments

0 comment