views

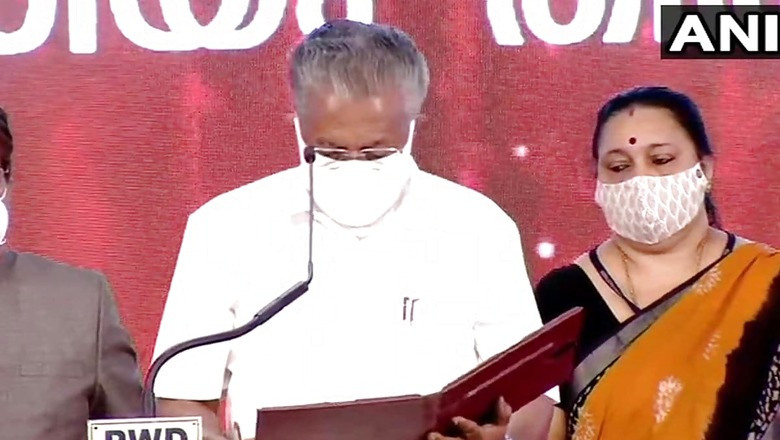

The second Pinarayi Vijayan government in Kerala sworn-in on Thursday, backed by its assertion of having conformed to COVID protocol, claims many firsts. The chief minister has reposed his faith in 17 first-timers in a 21-member strong team, which accounts for over 80 per cent of the cabinet. Three of his ministers are women, something that none of the earlier 14 state governments has achieved in the past. In one stroke, the Left Democratic Front (LDF) government has actually executed what other parties have often spoken about, both by retiring stale old faces and allowing more women to become cabinet ministers, which was to date largely an old boys’ club.

Ten of the 12 CPM ministers are newbies, the exception, apart from Pinarayi Vijayan himself, being K. Radhakrishnan, who was a minister way back in 1996 and a Speaker in 2006. Not only has ally CPI fielded four new ministers, one of them is a woman, but three of the remaining five ministers representing smaller allies are also fresh faces.

So, does that make it a case of old wine in a new bottle? Certainly not. Neither is it new wine in an old bottle. It’s more of new wine in a new bottle with an old cork or cap. But then, it was the captain who arguably won the mandate, almost single-handedly.

A Curation in Two Phases

Captain Vijayan, unlike in a football team, brooks no interference from the management and while the jury is divided whether it is a collective decision of the CPM think tank or a fond wish of the chief minister, the die was cast some time last year that when (and not if) the LDF gets a second consecutive term to govern, the chief minister would remain the same but the CPM would have no remnants from the earlier team.

Thus, on Tuesday, the CPM politburo members from the state unanimously passed the resolution to drop all incumbent ministers from the new cabinet, a plan that has been in the making for many months. This strategy, to cleanse the upcoming cabinet of all seasoned hands, was kicked off with the decision to drop two-time MLAs from the party’s candidate list for the 2021 Assembly election. If five senior ministers were thus taken out of the picture, the remaining five were put out to pasture when the decision to induct only fresh faces as CPM ministers was formally announced on May 18.

Clearly, the two-phase curating of the new cabinet was carried out with multiple purposes. The altruistic goal, evidently, is the moulding of a new team, ready to carry the Left legacy forward. At the same time, there is also another legacy being crafted here. Surely, it would be politically naïve to gloss over the legacy Pinarayi Vijayan is aiming to build during his second stint as the chief minister.

Having won a historic ‘bharana thudarcha’ (continuation of incumbent government), that too without leaning on the crutches of his long-time mentor V.S. Achuthanandan, the ‘Mission Possible’ is also about carving his own legacy—as the tallest CPM leader and the most efficient, if not the most revered, chief minister Kerala has ever seen. In the bargain, if he gets to choose his successor, then who can stand in his way?

Why Shailaja Was Dropped

And, the answer to the vexing issue of K.K. Shailaja getting dropped or rather not given an exemption from the “fresh faces only” rule can be found in the standing she enjoys or rather does not enjoy within the CPM state committee. Neither the media outrage nor the frenzied social media posts #BringBackOurTeacher found a resonance within the state committee, which made it clear there would be no exemption to the rule. The chief minister was always going to be an exception.

Of the 88 state committee members, only seven voiced their discomfort over not inducting Shailaja in the new government. The issue was not put to vote as even those seven decided to go with the majority. Shailaja, also present, could only remain a mute spectator. The party came up with the explanation that Shailaja too was a first-timer in 2016 and grew in stature as the health minister through the state’s handling of Nipah and COVID, primarily on account of the confidence reposed in her by the chief minister.

Shailaja too now admits that she could perform because she had an efficient team of healthcare and infectious disease specialists overseeing the fight-back and, of course, the CM’s support. Equally pertinent is the robust healthcare backbone Kerala has built over the last quarter of the century when it laid the foundation for a vibrant local self-governance mechanism.

With primary and community healthcare centres feeding the government district hospitals and the medical college hospitals as well as the advanced medical research centres, the network has so far proved to be an ample safety net for the state. With a slew of private hospitals and super-speciality facilities spawning across the state, adding strength to the age-old missionary hospitals, Kerala does indeed make for a dream state by way of healthcare, making it easier for health ministers compared to many other states.

At the same time, one cannot downplay the political fallout on account of Shailaja earning accolades on the global stage as the person responsible for the Kerala model of COVID fight-back. In hindsight, all that basking in the glory seems to have come at a cost.

On the one hand, the Chief Minister was personally engaging with the people of the state on a daily basis through COVID updates. While on the other, the health minister was seemingly painting a larger canvas, one of international proportions, wherein she rarely mentioned her CM. There was bound to be a cost. She paid a steep price. The Icarus analogy, although a bit stretched, is not completely off the mark.

But then, quite a few other ministers too had delivered the goods for the LDF government under their given portfolios. Thomas Isaac, with his fund-raising dexterity—although he took recourse to a controversial instrument like KIIFB (Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board)—allowed the government to bankroll its many projects, including the populist ones. G. Sudhakaran got a corrupt department like public works to deliver cost-effective and lasting roads, to date a rarity in the state; M.M. Mani provided largely uninterrupted power supply; C. Raveendranath was at the forefront of making government schools more sought-after than many private ones across the state. There were others too.

The harsh truth, unpalatable to many at this point, is that people would over a period of time forget Shailaja. Her successor Veena George will get in the driver seat, the debate whether she fared as well as her predecessor will taper off. Unless, of course, she really messes it up. Quite an unlikely scenario, given the robust healthcare foundation that Kerala had in place during Shailaja’s tenure remains intact.

Will the Nepotism Charge Stick?

Meanwhile, the chief minister seems unfazed about criticism regarding his son-in-law P.A. Mohammed Riyas being inducted into the cabinet, in charge of the critical public works portfolio. Surely, Riyas being the national president of DYFI (Democratic Youth Federation of India), apart from being a first-time MLA, does not tip the balance in his favour against the clear handicap of having his wife’s father heading the same cabinet.

The end word is, this is the first time Kerala has got a father-in-law, son-in-law combination in the state cabinet. Surely, the comrades would be uncomfortable when parallels are drawn with Donald Trump appointing daughter Ivanka Trump and son-in-law Jared Kushner as his senior advisors with considerable clout. Perhaps, they would be more comfortable fielding home-grown nepotism charges, having brushed aside many such allegations in the past and the election results a proof that voters are not devastated by such goings-on.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment