views

It has been a year since unprecedented violence took place in West Bengal after the Assembly election results were announced. Why Bengal has been suffering violence (both West Bengal and Bangladesh)? What was the original demographic composition of Bengal and how it has changed; and how this has affected the socio-political milieu in this region? This multi-part series would attempt to trace the origin of socio-political trends in the larger Bengal region (state of West Bengal and Bangladesh) over the last several decades. These trends are related to the evolution of Bengal over the last 4000 years. It’s a long journey and unfortunately most part of it has been forgotten.

The 19th century witnessed rise of anti-colonial nationalism in Bengal but it had its roots in the pre-colonial era. A common assertion put forward by most commentators and historians is that the national consciousness or nationalism awakened in Bengal for the first time during 19th century and it was the outcome of western education and exposure of Indian intellectuals to the western concept of nationalism. This is an outcome of colonial and Marxist interpretation of Indian history.

Fact is the philosophical base for 19th century reforms in Bengal can be traced to ancient Bharatiya heritage of ‘Sanatan Dharma’. The national consciousness was always there in Bengal, reflected in the way the Hindus resisted invasions, atrocities and subjugation by Islamic rulers in various parts of Bengal since 13th century (as explained in previous articles in this series).

However, after the arrival of the British, the national consciousness was more focused on opposing the British colonial rule. India wasn’t new to the concept of nationalism and neither was Bengal. What happened in 19th century was a reform movement led by Hindu reformers with a deep faith in Sanatan Dharma. They had realised that to fight the British colonial rule and bring greater equity in society, we need to go back to our roots and not let western frameworks guide us. And what better way to demonstrate it than what happened in the field of ‘Science,’ which was projected as a creation of the West.

In this context, let us take a look at the work and philosophy of four major scientists of Bengal in 19th century, though there are many more. The most interesting similarity between all four of them is that while they all belonged to one or the other discipline of science, their professional work and beliefs were deeply rooted in the Hindu philosophy.

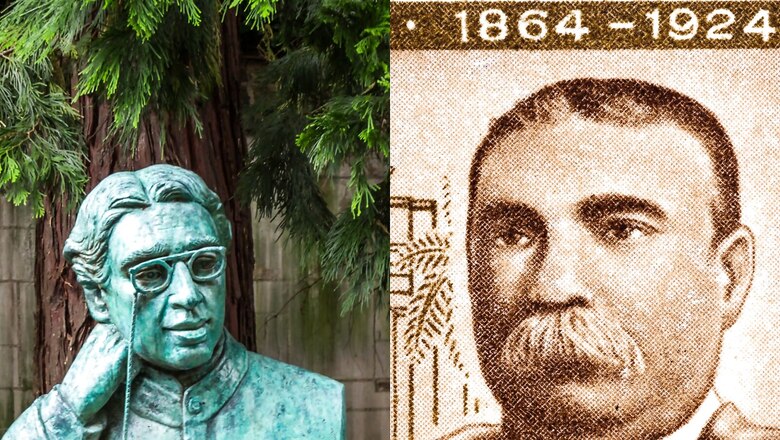

Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937)

He was a practising scientist who had studied at St Xavier’s College, Calcutta and Universities of Cambridge and London. According to J. Lourdusamy (Science and National Consciousness in Bengal; pp 6), “His research into the similarity between responses of metallic coherers and muscle tissues, and later on the interconnections between the plant and animal worlds, generated considerable unease in the scientific metropolis.”

“It was of particular significance that Bose drew inspiration for his new forays from the Vedanta philosophy of his inherited culture, which underlined the fundamental unity of all existence. Due to the draft of fresh air that he brought into the practice of science, Bose’s appeal went beyond the scientific community, to win the admiration of eminent men in different walks of life, such as Bernard Shaw, Gilbert Murray, Henry Bergson and Romain Rolland. Bose’s lasting gift to his country was the Bose Institute, which he founded in 1917,” adds Lourduswamy.

Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray (1861-1944)

An accomplished chemist, who had studied at the University of Edinburgh, Acharya Ray was also an inspiring teacher and a visionary Swadeshi entrepreneur. Exceptionally multi-dimensional, he worked on a grand project to unearth the scientific traditions of ancient India along with setting up a very successful industrial unit, Bengal Chemical and Pharmaceutical Works (BCPW), thus playing an important role in industrialisation of Bengal.

Acharya Ray’s seminal work A History of Hindu Chemistry was a path-breaking treatise. “The work, apart from highlighting Indian alchemical traditions, also contested Western historical accounts of chemistry which ignored the Indian contribution. More importantly it sought to inspire the contemporary generation. As attested by S.N. Bose, the celebrated partner of (Albert) Einstein in the Bose-Einstein statistics and one of Ray’s students, the work instilled self-respect in Indians with its indubitable proof of India’s ancient traditions of observation and experiment.” (Science and National Consciousness in Bengal; pp 16)

Ashutosh Mookerjee (1864-1924)

He was a trained mathematician and his brilliance can be gauged from the fact that some of his initial work in the field of mathematics was incorporated as part of the curriculum in the University of Cambridge. But Mookerjee despite being such a highly accomplished mathematician faced discrimination at the hands of the British government. He was not treated on par with other mathematicians from Europe when it came to employment, so he moved towards studying law and soon became an accomplished and successful lawyer. Later, he became the Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University where he took help of the locals to establish University College of Science (UCS) as a premier research institute in India. It is a well documented fact that Mookerjee was in favour of cultivating modern science along with cultural nationalism and promoting scientific research into India’s glorious past.

Acharya Ray described Mookerjee’s efforts as vice-chancellor in his foreword to Sir Ashutosh Mookerjee: A Study by Prabodh Chandra Sinha (Calcutta, The Book Company Limited, 1928), “(at a time when) nationalism and internationalism in culture (were) problems of the deepest moment, (Mookerjee tried to) sink his foundations of education deep into the wells of national traditions with the help of foreign machinery and at the same time took care that the foundation provided the most delicious beverage to all nations.”

Akshay Kumar Datta (1820-1886)

Datta taught Physics and Geography at Tattvabodhini Pathshala that was set up in 1840. “Datta, who declared that India needed a Bacon, presented science in highly religious terms while at the same emphasising the human mind’s enormous capabilities to understand the universe … Datta sought to further the acceptability of science by investing it with sacral values. His work ‘Bahya Bastur Sahit Manab Prakritir Sambandha Bichar’ exhorted its readers to explore the divine purposes as expressed in the laws of nature … Dutta emphasised the role of the mother tongue in the propagation of scientific knowledge. When Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar established many vernacular institutions, he opened a normal school to prepare qualified teachers for these institutions.’ (Science and National Consciousness in Bengal; pp 50-51)

It is important to note that the reform movement in Bengal in 19th century was at the core of Bengal Renaissance and subsequent emergence of an anti-British nationalist movement. It was deeply rooted in the ancient Bharatiya culture and yet it didn’t take any communal overtones. The Hindu reformers, be it scientists, social workers, educationists or monks like Swami Vivekananda, took a cue from the philosophy of Vedanta to talk about the fundamental unity of the universe and hence universal brotherhood. However, unfortunately, various ‘puritan’ movements in Islam in Bengal, during the same time, hardened the radical identity of Muslims which subsequently had serious consequences for Bengal. The next part of this series would take a look at these Islamic movements in Bengal during 19th century and how it became a counterfoil to the Hindu nationalism under the patronage of the British.

ALSO READ | The Bengal Conundrum: Battle of Plassey and the Myth of Siraj-ud-Daulah Being a Patriot

You can read other articles in The Bengal Conundrum series here.

The writer, an author and columnist, has written several books. One of his latest books is ‘The Forgotten History of India’. The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment