views

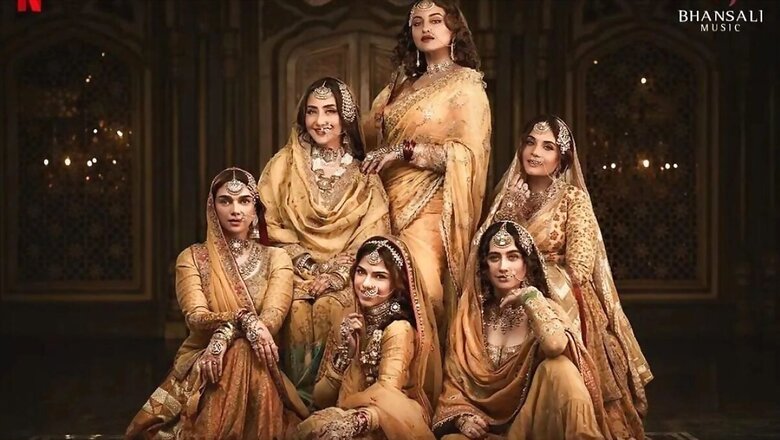

The mandatory pre-requisites for watching most “period” dramas on Indian screens these days is a near-total ignorance of history, along with an overwhelming appreciation of costumes, jewellery and surroundings to the exclusion of all else. Indians are by no means united on this count. That explains why so many people loved Heeramandi, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s lavish, debut small-screen offering. And also why so many people did not.

In fact, the most honest moment in the entire series is the disclaimer that appears at the start of each of the eight episodes. “Several characters, names and events in this series are fictional, and resemblance or similarity to any actual events, entities, places or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and unintentional.” That is SLB’s escape clause. The story, although set in mid-1940s Lahore, is not meant to be historically or factually correct.

Whew, with that out of the way, SLB let his stylistic imagination run riot. The only Schadenfreude-ish outcome of that is the reaction that the web series has evoked in Pakistan, whose denizens are outraged that Bhansali has ventured to set a costume drama in “their” Lahore’s Heera Mandi, complete with a freedom fighter bearing the irksome surname Baloch. Why no one in “Lollywood” had hit upon a Heeramandi tale all this while is equally apparent.

The divergence of negative opinions between Pakistan and Bharat on this series is quite telling. Across the Radcliffe Line, the anger is about gaffes such as an Urdu newspaper being read by a courtesan whose headlines include such “period” gems as “Warangal Municipal Elections: TRS Distributes Tickets” and “The Launch of a Scheme to Distribute 50,000 Masks by Youth Congress” as well as Professor Higgins’ type convulsions over Urdu pronunciation.

But it is actually quite scandalous that India’s cinema community, especially in Mumbai, now lacks the requisite domain knowledge to ensure its actors correctly pronounce certain sounds and its set designers know enough written Urdu to prevent that newspaper gaffe. Time was when the finest Urdu was spoken and written on “this side” of the border, with Lucknow and Delhi leading the charge. Now, shamefully, Pakistan has reason to claim it.

Indians, on the other hand, are more incensed by the over-stylised look of the production, to the point of blurring the storyline and stifling the expressions of the characters. Everything is so colour-coordinated and pristine that even the normal hustle-bustle of the ‘Shahi Mohalla’ of a big city like Lahore is omitted. It is so sanitized that it could just as well have been set in the Mughal emperor’s faux city inside Delhi’s Qila Mubarak or Red Fort.

No children, no stray dogs, no roosting pigeons, no garbage by the kerbside, no dust, no potholes, no trees or even leaves. There are no ambient street sounds, no strains of vocal riyaz wafting in the air, no vendors of jalebis or paya either. Yes, it can be said that SLB is merely paying homage to Bollywood history by evoking the aesthetic of Mughal-e-Azam, Pakeezah and Umrao Jaan. But technology has advanced a lot since then: why not use it for realism?

This devotion to stylised reality is why the absence of “real” politics is also not surprising—although maybe only history aficionados missed that dimension. How many know or remember that Lahore was where Jinnah first called for Pakistan in 1940? And since most (presumably) do not, the curious lack of reference to any major political figure and the obviously deliberate brushing out of the increasing communal tension goes unnoticed.

As one of the baghis—Bhagat Singh-like revolutionaries, all Muslims though Lahore had a considerable Hindu population before Partition—mentions the famine in Bengal while addressing a meeting of likeminded Lahoris, the setting has to be 1943-44, as there are also scenes of protest marchers chanting Bharat Chhoro along with Inquilab Zindabad. Only if viewers know contemporary history, which is by no means a widespread phenomenon.

Courtesans—tawaifs—actually playing a decisive role in the freedom struggle is not an improbable supposition; however, no one had actually explored it cinematically, so kudos to SLB for taking on Moin Beg’s novel on this theme and running with it. But to set in it an almost ahistorical context, neutered from reality is a bit much. As the context is deliberately underplayed, the characters appear to lack depth, and their actions seem like melodrama.

Why an Oxford-returned nawabzada suddenly joins the freedom struggle is unclear. Why he also blatantly comes onto an unknown young woman—who, for all he knows, could well be a nawabzadi—at a party at his mansion is also inexplicable. How the same girl, who he now knows is Alamzeb (a tawaif’s daughter) is allowed to stay as a “guest” with his Dadijaan cooing over her rather than frowning at the impropriety of it, is equally strange.

A point here about unreal appearances is germane too. Unlike in Heeramandi, blow-dried, artfully curled free-flowing tresses were never the norm in any part of undivided India, whether tawaifs or ‘respectable’ women at the time. Long tresses were let loose only in bed chambers; otherwise, they were washed, perfumed, oiled, combed and coiled into buns or plaits and embellished with jewels and flowers. Vintage photographs testify to that.

Those who have seen photos and movies of that time would also vouch that most men did not have bulging biceps and six-pack abs. Only wrestlers did. But, as in the case of 2023’s Jubilee web series set in the same era so also with Heeramandi, the leading male characters have gym-sculpted bodies, obligingly bared in towel-clad scenes—which now seem to be as de rigueur for today’s OTT plots as wet saree dance scenes once were for women in movies.

The current trend of the glabrous male torso and arms is also seen in Heeramandi, with even the gloriously thick-haired Tajdar Baloch baring a startlingly hairless chest even as the suggestively tousled Alamzeb languorously snuggles into her distinctively 21st-century duvet. Two of the three white characters don’t sound British—one has a distinctly European accent while the other sounds Indian; the only one who does get the accent right is an American!

And now, finally, to the acting. The huzoor (madam) Mallikajaan played by Manisha Koirala is intent upon her menacing drawl, almost to the exclusion of all else. But Koirala is saved by her superb acting skill from the dire combination of a melodramatic script and an over-ornate setting. Sonakshi Sinha as the vengeful Fareedan is lively but her scheming has a saas-bahu serial air; her Urdu probably has a nails-on-blackboard effect on current Lahoris.

Sharmin Segal Mehta as Alamzeb is a huge disappointment given that she potentially had the meatiest role. When it comes to wooden expressions, she even beat her screen-sister Aditi Rao Hydari (Bibbojaan) to it, with the same half-smile, faraway look and flat, husky delivery no matter whether in the throes of passion or pain, remorse or writer’s block. Hydari’s trademark deer-in-the-headlights look, seen in Taj and in Padmavat, is exactly the same here too.

Richa Chadha as the tragically unhappy tawaif Lajjo and Sanjida Sheikh as Waheeda (Mallikajaan’s bitter sister), two Punjabi-speaking female retainers, a Sikh coachman and a host of two-dimensional characters constitute a colour-coordinated but unexceptional backdrop to the main story. Sadly, despite being set in a dramatic time with an unusual plot, Heeramandi gets derailed by SLB’s unflagging obsession with aesthetics rather than substance.

But that makes for a very soothing experience too. And there is nothing wrong with curling up on the couch or bed with popcorn (with or without a significant other) to have an enjoyable weekend binge-watching an extravagantly mounted costume drama with evocative music and an uncomplicated plot. Even a weekday escape to SLB’s Instagramically perfect, weather-proof world is not bad as an antidote to the current heatwave and election fervour.

Ignorance of Indian history is evident in many Sanjay Leela Bhansali films; that many of them have nevertheless been commercial hits indicates if not the level of historical knowledge among Indians then certainly the importance most of us give it. “Don’t let facts stand in the way of a good story” is an adage that has been successfully adopted by people in spheres besides the film industry too, after all. And then there is always SLB’s escape clause…

The author is a freelance writer. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment