views

When we think about it today, we lapse into consternation and melancholy. The criminally nonchalant manner in which we have squandered away Bharatavarsha’s profound cultural imprint that had exercised an invisible but powerful suzerainty throughout a vast region in Asia. That the squandering occurred after independence magnifies the extent and scale of the crime. For example, Wayang Beber is today an endangered art form in Indonesia because Mankhas have become extinct in the very cradle they were birthed in – Bharata.

In fact, the legendary DV Gundappa had castigated the aforementioned cultural squandering way back in the early 1970s in memorable language (emphasis added): “Flirting with Russia and dreading China, India’s relations with America are ambiguous; and she must seem all things to all men and nothing in particular to any one, which is her non-alignment! And what gives poignancy to the reflection that we are so miserably incapable of going at least to the moral support of Cambodia is the recollection of the historical fact of our ancient kinship. once upon a time perhaps about the time of the beginning of the Christian era — Cambodia was part of the cultural empire of Hinduism.”

This is a proven fact of the Hindu cultural history: as long as the tempering, soothing and motherly palm of Sanatana culture exercised its silent influence on alien cultures, they remained largely sober. Despite successive Islamic invasions in many parts of Southeast Asia, the intrinsic Sanatana clime in that region remained unchanged. Even Persia, which had been wholly Islamised centuries ago, continued to draw inspiration from our culture and art forms. But the day India opted for the unwritten religious book of Nehru, known as secularism, the whole thing not only imploded but the loss became irretrievable.

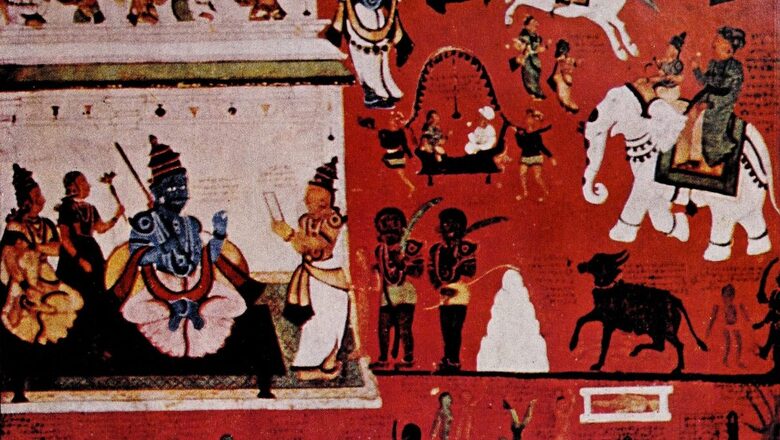

The earliest mention of Mankhas occurs in Sage Patanjali’s Mahabhasya. The work mentions the display of paintings (citra) depicting Krishna slaying Kamsa. The literal rendering of the text is as follows: “How in respect of the paintings? In the pictures, men see blows raining down upon Kamsa, and how he is dragged about.”

The clear inference from this is that the tradition of displaying these paintings in public such as in exhibitions, fairs, etc., was already in vogue during Patanjali’s era, and Mankhas or picture showmen were already a recognised profession. Jaina Prakrit texts unambiguously define the term Mankha as “a professional picture showman” and he is clubbed in the group of entertainers such as actors, dancers, storytellers, etc.

The Bhagavati Sutra mentions the name of Gosala Mankhaliputta (also known as Maskari Gosala, Makkhali Gosala). The Mankhaliputta refers to the profession of Gosala’s father, who was a Mankha.

A Sanskrit gloss describes Mankhas as citraphalakavyagrakara-bhiksu-visesa meaning, a bhikshu or mendicant who takes alms by exhibiting pictures of deities which he carries with him. In general, there are copious Jain texts mentioning and extolling talented Mankhas.

Long story short, by the post-Gupta era, picture exhibitions as an art form were flourishing. The art form would retain its prime position until the British colonial period. In fact, the story of its evolution is quite thrilling. From exhibiting and narrating picture scrolls showing Kamsa’s pummelling at the teenaged Krishna’s hands, the focus shifted almost exclusively to something known as the Yamapattaka or Yamapata. The Yamapata showed picture scrolls representing virtuous and evil deeds and the reward and punishment arising therefrom in Yamapuri, the abode of Yama. Major Sanskrit literary works mention Yamapattakas or picture showmen who painted Yamapatas.

In Vishakadatta’s renowned play Mudrarakshasa (based on the life and legacy of Kautilya), dateable between the 5th and 9th century CE, Kautilya’s spy, Nipunaka disguises himself as a picture showman. He says that men earn their living by portraying the same Yama who kills people. Then he enters Chandanadasa’s home, carrying a scroll with figures of Yama upon it. But before he enters, this is the dialogue he utters: “I will enter here, show my pictures and chant my song (yamapatam darshayan gitaani gayami).” After his errand is over, he brings a report to Chanakya saying in Prakrit, “Spreading out the Yama picture scroll, I commenced my song. (jamapadam pasariya pauttohmi gidaim gaidyum).”

Banabhatta’s Harshacharita paints a vivid portrait of picture showmen: “Like those who depict Naraka, loud singers paint unrealities on the canvas of the air…In the market street amid a great crowd of inquisitive children, he observed a Yamapattaka in whose left hand was a painted canvas stretched out on a support of upright rods and showing the God of Death mounted on his fearsome buffalo. Wielding a reed wand in his other hand, he was expounding the features of the next world, and could be heard to chant the following verses…” (Verses clipped for this essay)

The prolific translator of Sanskrit literary works, MR Kale, in his notes on the Mudrarakshasa, writes, “The exhibition of Yamapata was one of the sources of making money.”

Likewise, KT Telang’s edition of the same play says this about Yamapata: “A series of representations of the exploits of Yama, something like the boxes of sacred pictures which are shown about to this day.” And Telang too, gives a reference to the aforementioned passage in Harshacharita.

Writing in History and Culture of the Indian People, NR Ray gives us a brilliant description of the Yamapata and its various offshoots: “Yamapatas were executed on textile scrolls and dealt with themes of a narrative — didactic nature, showing the results of Karma in the other world. Buddhaghosha, the celebrated Buddhist scholar… refers to a similar kind of painting to which he gives the name of charanachitras which consisted of scenes of happy and unhappy destinies of men after death with appropriate labels attached to them and shown in portable galleries. There can be no doubt that these yamapatas or charanachitras are the ancestors, in form, meaning and presentation, of the patachitras that are widely current in Eastern India…”

As we mentioned in the previous article, like all else in the Hindu cultural life, this tradition of a sub-genre of art too shows our unbroken continuity. NR Ray concludes his assessment on a sombre but profound note: “No contemporary example of Yamapata or charanachitra…has survived to this day; but it was evidently a folk-art of ethnic and religious significance and wide popular appeal, an itinerant school of deep and great educative value for the rural masses.”

The author is the founder and chief editor, The Dharma Dispatch. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment