views

Let us face it. Indian liberals love Pinarayi Vijayan. He has just won a historic second consecutive term as the chief minister of Kerala, breaking the decades-long incumbency cycle in the state. By his side, he has his trusted lieutenant K.K. Shailaja, the so-called rock star health minister of Kerala. Together, they bask in the glory of the now-famous Kerala model of coronavirus management. From fawning interviews with BBC to glowing coverage from The New York Times and Al Jazeera and gushing praise from the MIT Tech Review, there seems to be nothing that the duo cannot have.

Except for one thing—control over their own party. The leadership of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or the CPI(M) rests with Sitaram Yechury, the general secretary of the party.

Indeed, the structure of the Communist Party remains one of the great oddities of Indian politics. Kerala is now the only state where the Communists still have a mass base. Pinarayi Vijayan and his associates are the only mass leaders left in the party. However, the reins of the party remain firmly with those who are neither mass leaders, nor vote-getters. Although inherently undemocratic, the system within the CPI(M) continues to be stable, even unchallenged.

One cannot but notice something here. Sitaram Yechury is a Brahmin, while Pinarayi Vijayan and K.K. Shailaja are not.

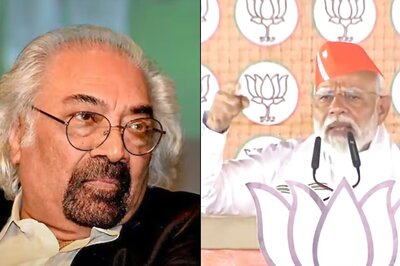

The BJP often has to contend with the charge of being a party of upper castes. This charge is continually magnified by sections of media, academia and scholars writing about Indian politics. And yet, the BJP was perfectly happy to replace its old Brahmin leadership with Narendra Modi. Indeed, by 2013, the clamour for Modi was so organic and so widespread among the BJP workers and supporters that the party simply could not ignore it.

The rise of Narendra Modi in 2014 meant a number of other things. For the first time, a regional leader rose to acquire a national profile and not by coincidence, but very deliberately. He also empowered with him a group of persons who were uncomfortable with the ways of the Delhi elite, but who nevertheless represented a new India that was assertive, unapologetic and full of aspiration.

At the opposite pole of political ideology, the CPI(M) has tried no such thing. It has made no space for lower castes, mass leaders, regional leaders, youth leaders or anyone who might represent something different from the old. Even when the CPI(M) was dominant in Bengal continuously for over three decades, the party in Delhi did little to accommodate leaders from Bengal. In its entire history, the CPI(M)’s all-powerful Politburo has never had a member from the Dalit community. This unravels the staggering hypocrisy of an organization that claims to speak for the most marginalized in society.

In public at least, the CPI(M) rejects all kinds of caste identities. This would be fine, except they also appear to reject the realities that are tied to caste in India. Any practitioner of social science would tell you that upper caste leaders claiming to dump their privilege is a show of privilege in itself. By making a simple declaration, one cannot walk away from upper caste privilege any more than a member of a marginalized community can walk away from their lack of privilege.

The problematic relationship of Communists with caste goes deeper, down to the level of party doctrines and ideology. In fact, E.M.S Namboodiripad, the first Communist to become the chief minister of Kerala, had argued that the caste system was a “superior economic organization.” In his worldview, the caste system provided an efficient way of organizing society by giving each member an occupation they were born into. While Indian Communists today probably would not say such a thing in public, the fact that no Dalit has ever been admitted to the Politburo since 1947 speaks much louder.

There is a final mystery here. How did we as a nation allow the Communists to corner so much of the academic discourse around social justice? Through a pretend embrace of Ambedkar and by taking the lead in writing revolutionary anti-caste slogans, the Communists have managed to push real questions about their conduct under the carpet. Putting upper caste leaders in charge regardless of merit, putting unelectable leaders over mass leaders is not superior political organization, but undemocratic. All political parties in India have a responsibility to adhere to basic principles of our democracy, which are the same as basic principles of fairness. And when parties step over these principles, all citizens, including those who disagree with them politically, have a responsibility to call them out on it.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment