views

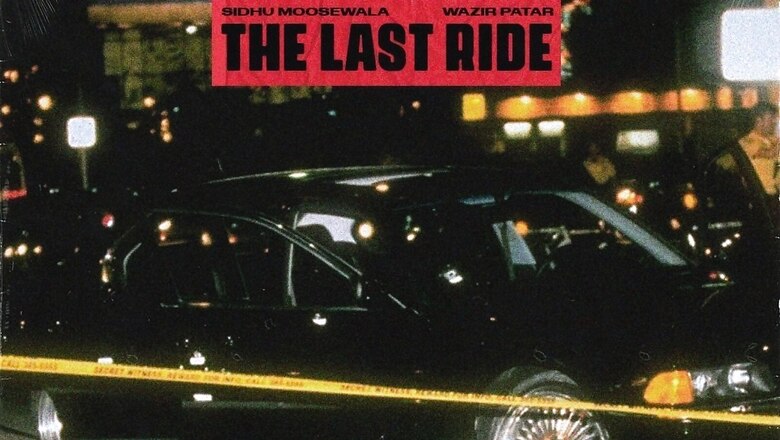

Punjabi singer Shubhdeep ‘Sidhu’ Singh Moose Wala swore by the gun in his songs, including ‘Warning Shots’. Residing in a musical culture ‘obsessed’ with arms, no one had expected that on a warm Sunday it would be the gun that would silence Moose Wala’s song forever near Mansa in Punjab.

Sidhu’s death came weeks after Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann had asked young singers with huge fan following to desist from using themes related to violence and drugs. He had also warned of action if they continued to violate ‘ethical’ codes.

But Mann is not alone. Before him, his predecessors Charanjit Singh Channi and Capt Amarinder Singh had also attempted to tame the themes of the musical culture in the state, which is plagued with cases related to drug and gang violence.

Capt. Singh had ordered a special drive to check such video and audio snippets, while Channi proposed a law to prohibit such music and movies. And it was during Singh’s reign that Sidhu was booked for encouraging violence through the screening of the film Shooter, which was supposedly based on the renowned criminal and was later banned.

But Sidhu is not alone in pursuing similar themes in his music. This is where the line thins between administrative action, culture and trends in the face of a growing problem in the state.

The Problem On Ground

The gangster culture of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar has always taken centrestage especially when it comes to Indian films, which have not dwelled too much upon the happenings in the badlands of interior Punjab and Haryana despite the fact that several ‘encounters’ have taken place in these states in the past few years.

Be it the Lawrence Bishnoi gang, Jaggu Bhagwapuria gang, Shera Khuban gang or Sukha Kahlon gang, successive state governments have always promised the people action against them, but little seems to have been achieved on the ground.

Amid allegations that many gangsters enjoy patronage of several politicians, the police have increasingly found it tough to reign in their activities that include targeted killings, smuggling, extortion and drug peddling, writes Sukant Deepak in a report for the IANS.

Where Culture and Art Collide

Mann, while issuing his warning against violence themes in media, had said that their glorification had led to rise in anti-social activities in the state. Mann had said Punjabi artistes and their work should play a constructive role in upholding the rich cultural legacy of the state.

“It is our prime duty to prevail upon such singers not to encourage violence through their songs which often pervert the youth, especially children with impressionable minds,” Mann had said.

No one can deny the influence artists like Sidhu have on the youth. At any given time, many youngsters could be seen outside his house in Mansa — to shake hands with him, to take a selfie with the singer who reached cult status in his youth.

But at the same time, the line is always blurred between representation of cultures and audience demand when it comes to creating art. Sidhu’s own music often seemed to borrow from hip-hop among other styles. The music style, attributed to being developed in the United States, is often partly seen as a ‘reaction to the socio-economic conditions in Black and Brown neighbourhoods’.

Daljit Ami, a noted writer-filmmaker and director of Educational Multimedia Research Centre, Punjabi University at Patiala, told the Outlook in a report that when it came to Punjabi cinema, the industry had seen tremendous improvement in production quality and expansion of distribution networks in recent years, but that “most of the movies still revolved around old subjects that reinforced the regressive value system.”

‘Social Responsibility’

Ami, who has worked on a range of films on social issues, said that while the success of films on mainstream topics could not be compared to the former, the money spent on these was ‘always recovered’. According to him, Punjab society is afflicted with problems like drugs, violence, casteism and patriarchy and “that filmmakers must feel socially responsible to address these issues.”

“The art must challenge social evils instead of endorsing them. If your movies celebrate all these issues, you may make a lot of money, but you will be failing as an artist,” Ami said in the report. “The question remains whether cinema being a commercial entity wants to humanise the society or not.”

Speaking on music culture, writer and poet Surjit Patar told Tribune India: “It’s not just the violence, repetition of words and music on limited subjects that is worrisome. Our singers are moving away from the culture Punjab represents. Punjabi music has rhythm; bhangra and dhol should go a step further with lyrics.” He says a long term goal “should be to enhance the audiences’ taste in all the art forms by exposing them to good content.”

But not everyone is convinced. According to Lyricist Gill Raunta, artists “write what we observe”. “An artistes’ work is mirror to the society. Vailpuna and Hathyar are not new words; I won’t deny that songs leave an impression on people but the society also determines what is being written. More than the violence, the vulgar-vocabulary in songs is a bigger issue,” he told Tribune India.

The Path Ahead?

Governments in Punjab seem to acknowledge the problem that persists, but what seems to be the consensus is that it is a multi-pronged problem. Politicians in the Opposition in Punjab, reacting to Sidhu’s murder have pointed fingers at the persisting ‘law and order’ problem in Punjab.

Action in such cases against artistes creating on such themes is not new, but the incident has now sparked a deeper conversation – of where the problem begins, and where it could possibly end.

Read all the Latest Explainers here

Comments

0 comment