views

New Delhi: They set out from Bhajanpura in Delhi on Friday covering 25km on foot to reach the Uttar Pradesh on Saturday morning.

Shailesh, his wife and their two toddlers -- Aanya and Rishi -- are now waiting for some mode of transport to take them to their village in Auraiya district. Else, they would have to cover the remaining 300km on foot as well.

“If we do not get any transport, we will start walking again,” the woman says.

Shailesh is a carpenter and earns about Rs 8,000 a month. For the last one month, he has been out of work. And for the last six days, he says, there was very little to eat. “The children haven’t eaten anything since morning,” says Shailesh.

With India declaring a nationwide lockdown to control the spread of coronavirus, migrant labourers who struggle to make ends meet are facing another daunting challenge – returning home.

“There is no work here. We have no money, what will we do here in Delhi,” Shailesh says.

However, just they were about to take the long road ahead, a state transport bus arrived. The bus would ferry passengers to Etawah, not far from Shailesh’s home.

But not everyone has been as lucky. With no trains or buses or any other modes of public transport available, many people are walking back home.

Parveena Begum have been walking from Rithala with three children -- all of them below 10 years. Their destination is Badaun in western UP.

Parveena’s husband had gone home to attend a wedding last week. Soon after, curfew was imposed and he could not come back.

“The children are hungry. We don’t have money, but we will keep walking,” she says.

The UP government has decided to ply 200 state transport corporation buses to bring back hundreds of migrants stuck in the National Capital Region. The buses will continue to operate for the next two days, an official said.

Preeti and Pawan with their nine-month-old son are waiting for a a bus since morning. Pawan works in Manesar, an industrial town along the Delhi-Haryana border. After work stopped due to the lockdown, the family decided to return home. They have been walking since noon on Friday.

With Rs 500 in pocket and some food, the couple is determined to reach home, even if takes days of trudging on the roads.

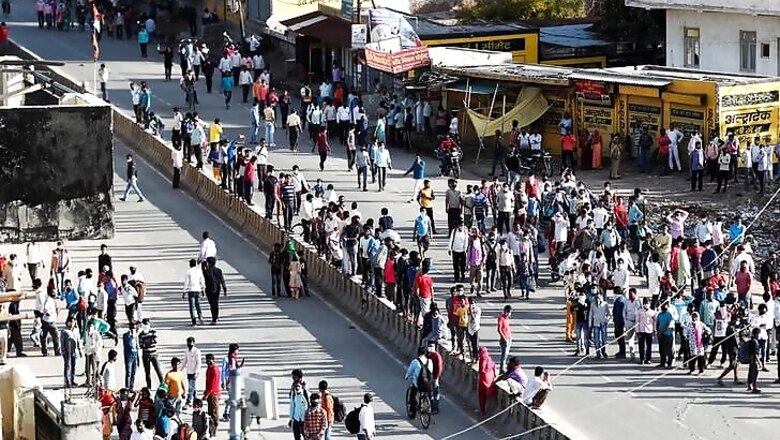

As thousands squatted on the pavements, every now and then, someone is heard saying the buses would arrive soon. A small tractor moved past with some sacks. A few tried to jump on to hitch a ride.

All this while, policemen kept a close vigil making regular announcements. A few minutes past 11, the first bus for Moradabad arrived. Minutes later, the second one came for Etawah.

Passengers scrambled for seats, but the buses were not yet crowded. The lucky ones got onto the bus, while others waited for their turn.

Meanwhile, as the buses started arriving at the Delhi-UP borders and at the capital's Anand Vihar Bus terminal, word spread like wildfire amongst the entire migrant community in Delhi, that buses would take them to UP, through phone and WhatsApp. Delhi government had started plying its buses from Anand Vihar Bus Stand to Hapur. Towards late morning more and more people streamed out of their houses that included single families, groups of young men, entire communities carrying their meagre belongings all heading towards Anand Vihar Bus Terminal, Ghaziabad, Noida, Badarpur Border, primarily on word of mouth information that buses were plying.

Satya Narayan, a daily-wage worker, along with his wife and two kids, was just one among thousands on the road. "Lemon and water, some medicines and a few rotis is what we are carrying. The landlord gave us about Rs 70," he said, carrying a kid on his shoulders while the other walked alongside his wife. From Chhatarpur, Satya Narayan headed towards the Badarpur border. When asked what he would do in case he does not find any bus, he said, "If we do not get buses, we will walk. Our CM Yogi Adityanath has said (he will send buses) for those who are on the roads, plus we have their landline number, we will inquire, get a bus and go home."

As the various streams from differents parts of the capital reached Anand Vihar Bus Terminal, it turned into a massive torrent, inundating the bus terminal. A massive exodus on the fourth day of the 210day lockdown, the sheer scale of the reverse migration of India's most vulnerable is unprecedented in recent memory. The destitute migrants had made up their minds and Kejriwal's repeated pleas fell on deaf ears.

The scale of migration to Delhi from adjoining provinces can be gauged from the fact that between April 2015 and March 2016, close to 18 lakh people (1.8 million) bought tickets for unreserved compartment in trains to the national capital from drought-hit Bundelkhand.

They had left their homes for Delhi in search of jobs. They mainly came from 10 railway stations of Bundelkahnd -- Atarra, Banda, Jhansi, Mauranipur, Mahoba, Khajuraho, Kulpahad, Harpalpur, Manikpur, and Chitrakoot.

Many had borrowed money for tickets that would cost less than what many of us would spend on a cup of coffee at a food joint in Delhi. Now, many would be returning home walking with not even that much in their pockets.

Comments

0 comment