views

Most of the houses in Pachara village in Mahoba district of Uttar Pradesh are locked and entire families gone. Most of them left between four to six months ago, after the Kharif season failed. The next wave of exodus will begin after Holi.

Most of the houses that are locked belong to people who have less than five acres of land. Compensation for crop that was lost in 2013 and 2014 was received by villagers in only early 2016. People who are still in the village are sticking around for the compensation

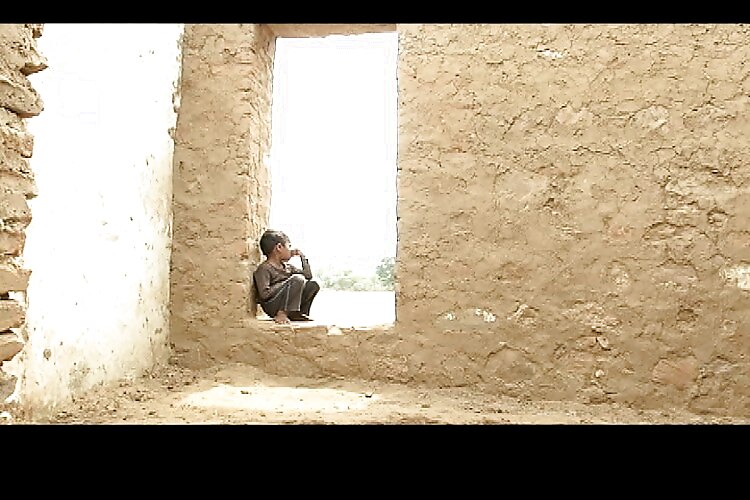

Jitan's parents Shanti and Raju left for Bahadurgarh near Delhi three months ago after they lost the chana (gram crop) on their two bighas of land. They left Jitan behind with his grandparents and his brother Shivam with his uncle in Maharajpur in Chhattarpur district. Jitan does not talk much. He waits all day for his parents to call. Children run towards the camera when they see one in the village, but Jitan is unmoved.

"The parents call sometimes. They send Rs 200, 500 or 1000 so that we can survive," says Jitan's grandmother Phoolwati.

Besides young children, the people left behind in the villages are the old.

Kalicharan and his wife have been on their own for several months, since both their sons left. In January 2016 they received Rs 500 from one of them. They are making do with that and the Uttar Pradesh government compensation of Rs 2800 for the wheat crop that was destroyed by hailstorm twice.

ALSO READ: Famine-hit Bundelkhand in distress; chapati-salt becomes the staple food

Kalicharan's wife says they had borrowed money for seeds but the crop failed.

The village has 22 hand pumps but only two are working in the village. Most of the 13 wells are dry. The two ponds in Pachara are also dry.

ALSO READ: As Bundelkhand battles famine, schemes and packages fail to deliver

Belatal station is situated in the back of the beyond in Bundelkhand. No announcements are made when trains arrive at Belatal. But approximately 900 people leave take a train to Jhansi or Mahoba and from there to Delhi from Belatal.

People flock to escape villages that have run dry and where food is scarce. A couple and their three children, the youngest is less than a month old, are heading to Gurgaon in the NCR to find work on construction sites.

"There has been a famine for the last 3-4 years. We had taken loans for diesel. We had sown chana (gram), wheat and jowar but all dried up," says the husband.

Rati Ram, an old man travelling without a ticket, says he does not have the money for the ticket. "I will get food if I am caught and jailed."

Daya Ram has always been proud of the fact that he and his "do bigha zameen" (less than an acre) have been able to withstand Bundelkhand's trysts with droughts. But this time he has had to accept defeat. He is going to Delhi to look for work and has pulled his daughters out of school so they can accompany him.

Savita, his daughter, says, "We had to drop out as there is no money. We will join school again after we return." Daya Ram adds, "When there is no money to eat, then how can I send them to school. There has been no crop."

Many migrants are sitting on the railway tracks at Belatal railway station with their sacks on the track. A ticket from here to Jhansi costs Rs 10 which is one of the reasons why the station is so crowded. For villagers seeking to escape hopelessness and poverty, the station is one of the lifelines.

There are many old people who are making the journey for the first time, couples who have left behind children below five at home, and mothers travelling with babies as young as 20 days old. All of them have the same refrain - drought and hailstorm destroyed their crop.

The passenger train arrives and people scramble to get into it. One young family does not get a seat. The train leaves and in an instant the station is suddenly very, very empty. The sun also sets for the day over the Belatal station lush with palash (flame of the forest, a bright red coloured flower) blooming the only colour in the grey lanscape.

Mahoba railway station is no different. Khubchand and Vimala are from Bilki village and they have bought their tickets to Delhi. Their seven bighas of land yielded nothing. They have three children with them, and a sack with about 10 kilos of wheat flour (aata). Until they find work in the city, the flour will be critical.

When the UP Sampark Kranti Express enters the Mahoba platform, they rush with the hope of getting a seat. More than 1000 people will try to get in for half the number of seats. Conservative estimates say approximately 4 lakh people have already migrated to Delhi just from Mahoba in 2016 alone, but the figure seems to be a gross underestimation.

Vimla ran with two children and Khubchand with the sack of aata and another child. But they cannot enter into the first compartment. It is too crowded. They move to the second one. After much push and pull, they manage to get in. Vimla sits near the door and that's the way she remains till she reaches Delhi.

"Why would we migrate to Delhi if we had got some work in the village? Till now I borrowed from others to buy food. But for how long! If I take a loan, then I will also have to pay back," says Khubchand.

The story of Bundelkhand's drought can be told from the railway stations in the region. Every traveller from the region has the same litany of tales - of when it rained; of how it didn't rain enough; of hailstorms; of wheat, arhar, jowar, rai, chana crops that failed one by one. They also point out how hand pumps do not work and ponds, wells and canals have run dry, how compensation does not reach on time, if it reaches at all and how the hostile city may offer food and a chance of survival.

Local people say that they have never experienced a drought that is as devastating as the present one. Government interventions can certainly help but only to a certain extent but they can never fully compensate for the loss of incomes.

Speaking in the Rajya Sabha, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had quoted the famous poet Nida Fazli: "Safar mein dhoop toh hogi, jo chal sako toh chalo; sabhi hain bheed mein, tum bhi nikal sako toh chalo; kisi ke waste rahen kahan badalti hai, tum apne aap ko khud hi badal sako toh chalo; Yahan koi kisiko raasta nahi deta, mujhe gira kar agar tum sambhal sako toh chalo."

The Prime Minister had used the above lines to describe his predicament. Perhaps the poet's words are equally applicable to all the migrants who travel every day for survival.

Even as a young boy plays the song "duniya mein itna dukh hai, mera dukh kitna kam hai", young children have fallen asleep, with one’s leg on the other’s face, on the floor of the compartment. While the train gathers speed and the compartment swings from side to side, quite the opposite of a cradle, small children kids sleep even as adults are awake.

The train halts at Harpalpur at midnight where more migrants are waiting but the train is just too crowded to get on. Disappointed, with their loads on their heads, children on their hips and in their arms, they watch as the train pulls away.

The tickets cost Rs 180 to 190 depending on whether it is purchased them from Mahoba or Khajuraho. It is almost the same amount that many would spend buying a cup of coffee at Starbucks but in Bundelkhand many people have taken a loan to but the ticket and which they have to repay with interest.

As Delhi draws closer we ask people looking for a chance at survival if they have any dreams

Vimla stoically replies, "I don't have any dream."

"Just as we keep straw and chaff for the cattle after harvesting wheat, similarly the government gives the farmer what is left over," says a migrant from Bundelkhand.

As the train reaches Hazrat Nizamuddin station in Delhi, Khubchand and Vimla get down with their children and the sack of flour. Slowly, all the migrants stream out of the platform, onto the overbridge and the road at Nizamuddin crossing and disappear into a crowded Delhi.

Comments

0 comment