views

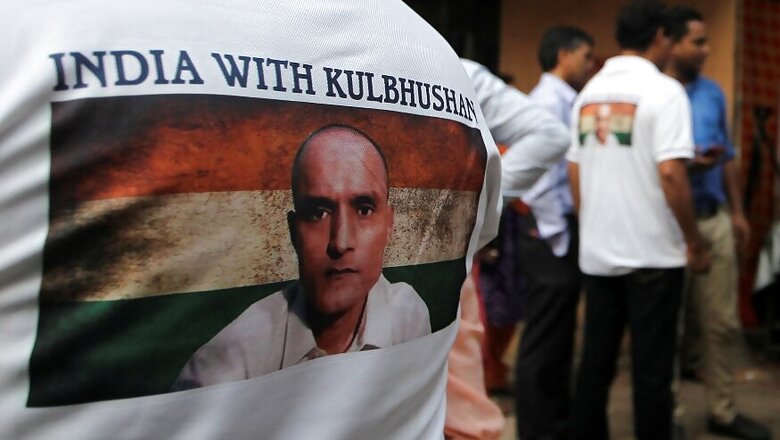

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has once again reiterated that the judgment in the Kulbhushan Jadhav case is “binding, final and without appeal”. This was the court’s response to a query by CNN-News 18 regarding the matter with one year having lapsed without the verdict being implemented by Pakistan.

Ostensibly, in May, Pakistan passed an Ordinance for review, a petition for which was to be filed within 60 days. That window closed on July 20 without any word from either Pakistan or India as to whether the petition could be filed for Jadhav. India had earlier said “it would consider all appropriate options” to ensure his safe return. Government sources had indicated that going back to the ICJ was an option. However, as per the response to the query from ICJ, no such move has been initiated so far.

Meanwhile, despite the ICJ order being “binding” on Pakistan, here’s a look at all the points in the ICJ order it has failed to implement.

The ICJ had concluded that Pakistan had “breached the obligations incumbent on it under Article 36, paragraph 1 (a) and (c), of the Vienna Convention, by denying consular officers of India access to Mr. Jadhav, contrary to their right to visit him, to converse and correspond with him, and to arrange for his legal representation.”

Since last year, Pakistan has ostensibly given India two meetings with Jadhav but do any of these qualify as consular access? India says, no. The June 16 statement by MEA spokesperson Anurag Srivastava said, “Consular access being offered by Pakistan was neither meaningful nor credible.” On July 16, when Indian Consular officers went for a meeting to the Pakistan MoFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) office on a reassurance that the meeting will be “unimpeded, unhindered and unconditional,” here’s what transpired as per India’s statement.

Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Anurag Srivastava stated after India had received a report from Charge d’Affaires Gaurav Ahluwalia that “Consular Officers could not engage Shri Jadhav on his legal rights and were prevented from obtaining his written consent for arranging his legal representation”.

The ICJ judgment had clearly mentioned, “Pakistan’s contention that Mr. Jadhav was allowed to choose a lawyer for himself, but that he opted to be represented by a defending officer, qualified for legal representation, even if it is established, does not dispense with the consular officers’ right to arrange for his legal representation.”

In fact, Judge Robinson had said: “Without a foreign national’s consular officer being able to arrange for his legal representation, it is very likely that none of the seven rights set out in Article 14 of the Covenant would be given effect. In that bundle, the right that is most at peril in relation to a person in a foreign country facing a criminal charge is the right under Article 14 (3) (b) “[t]o have adequate time and facilities for the preparation of his defence and to communicate with counsel of his own choosing”; it is also a right that is closely connected to the right of the foreign national to have that national’s consular officer arrange for his legal representation.”

The court had also inferred from Pakistan’s position during the hearing that it did not inform Jadhav of his rights under Article 36, paragraph 1 (b), of the Vienna Convention. It had thus concluded “that Pakistan breached its obligation under that provision”.

Secondly, the ICJ ruling had said, “The Court considers the appropriate remedy in this case to be effective review and reconsideration of the conviction and sentence of Mr Jadhav.” This process is yet to effectively start despite Pakistan ostensibly passing an ordinance on May 20 -- International Court of Justice (Review and Re-consideration) Ordinance 2020 -- as per the ICJ ruling saying this is to be done “if necessary, by enacting appropriate legislation”.

The Ordinance said that a High Court “shall examine whether any prejudice has been caused to the foreign national in respect of his right of defence, right to evidence and principles of fair trial, due to denial of consular access according to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations of 24th April, 1963”.

However, the Ordinance set out a timeline of 60 days for the review petition to be filed. Two weeks before the deadline, Pakistan announced that Jadhav had refused to file a review petition. India reacted by pointing out that, “Shri Jadhav has been sentenced to execution through a farcical trial. He remains under custody of Pakistan’s military. He has clearly been coerced to refuse to file a review in his case.”

Moreover, during the arguments, the court had observed that the Vienna Convention doesn’t make any exception even in cases of alleged espionage with regards to consular access and that it should be provided “without undue delay”. India in its statement on July 16 mentioned that, “Over the past year, India has requested Pakistan more than twelve times to provide unimpeded, unhindered and unconditional consular access to Shri Kulbhushan Jadhav, who remains incarcerated in Pakistani custody since 2016.” The delay here in providing consular access is glaring.

The ICJ judgment also noted that Pakistan flouted the Vienna Convention “by denying consular officers of India access to Mr. Jadhav, contrary to their right to visit him, to converse and correspond with him…” On this aspect too Pakistan has been found faltering.

The India consular officers on July 16 reported back to New Delhi that “Pakistani officials with an intimidating demeanour were present in close proximity of Shri Jadhav and Consular Officers despite the protests of the Indian side. It was also evident from a camera that was visible that the conversation with Shri Jadhav was being recorded. Shri Jadhav himself was visibly under stress and indicated that clearly to the Consular Officers. The arrangements did not permit a free conversation between them”.

Comments

0 comment