views

New Delhi: From March 2016 to March 2017, only 727 new Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) — the frontline health workers in the country — joined the workforce.

A mere 660 additional doctors were added to staff primary healthcare centres (PHCs) — the first point of contact between rural India and a medical officer — keeping the country’s doctor-to-population ratio well below the global standard of 1 for 1,000 (1 doctor per 1,000 people).

The latest set of data on healthcare in rural India — out in the government-compiled Rural Health Statistics (RHS) 2017 — paint a picture of painfully slow increase in numbers of doctors, nurses and health workers, and a skewed focus on building infrastructure which has no one to man it.

The three-tiered rural health system rests on the presence of sub-centres, often run by ANMs or female health workers, PHCs, and community health centres (CHCs), which are supposed to have four specialists — physicians, surgeons, gynaecologists and obstetricians, and pediatricians, along with the nursing staff and lab technicians.

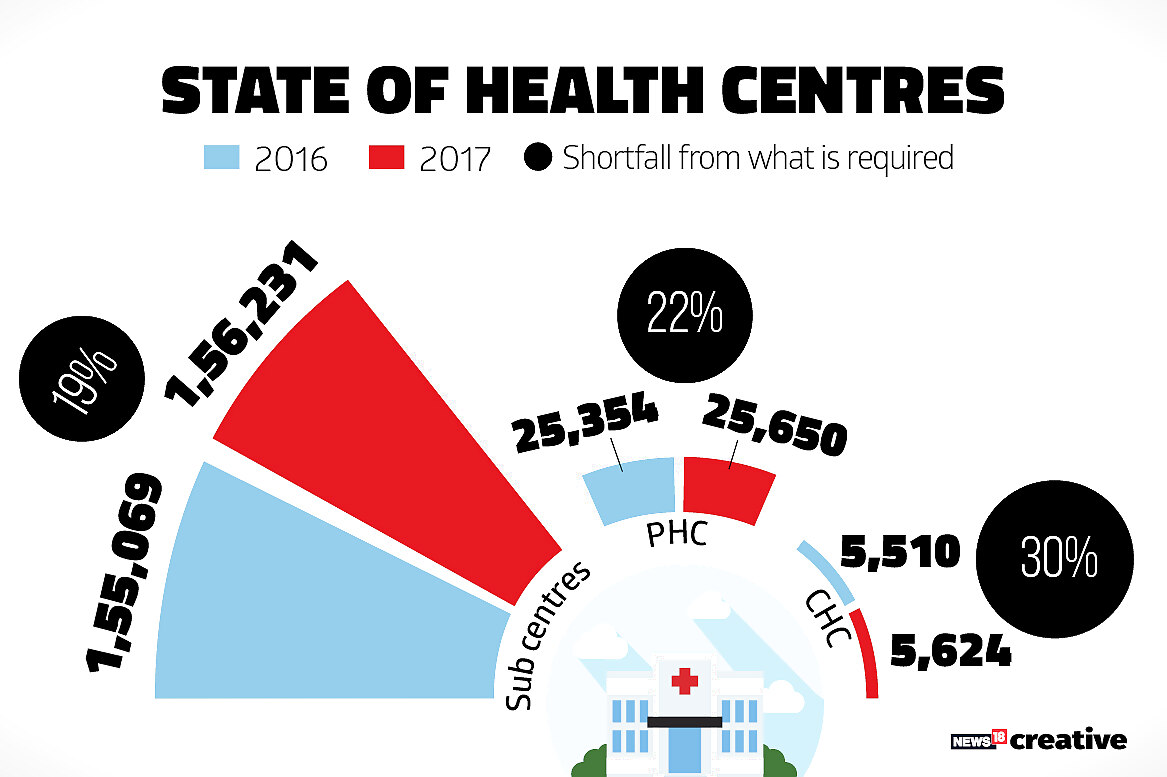

As of March 31, 2017, there were 15,6231 sub-centres, 25,650 PHCs and 5,624 CHCs in India, up marginally from 2016 and 2015.

The report pointed out that sub-centres had increased by 6 percent, PHCs by 9 percent and CHCs by 65 percent since 2005, the year before the National Rural Health Mission was launched, taken as a baseline year taken by Rural Health Statistics bulletins.

However, it admitted that “the current numbers are not sufficient to meet their population norm”. Data show there is a shortfall in infrastructure — 19 percent in sub-centres, 22 percent in PHCs and 30 percent in CHCs.

Of the operational CHCs, only 454 or 8 percent are manned by all four specialists.

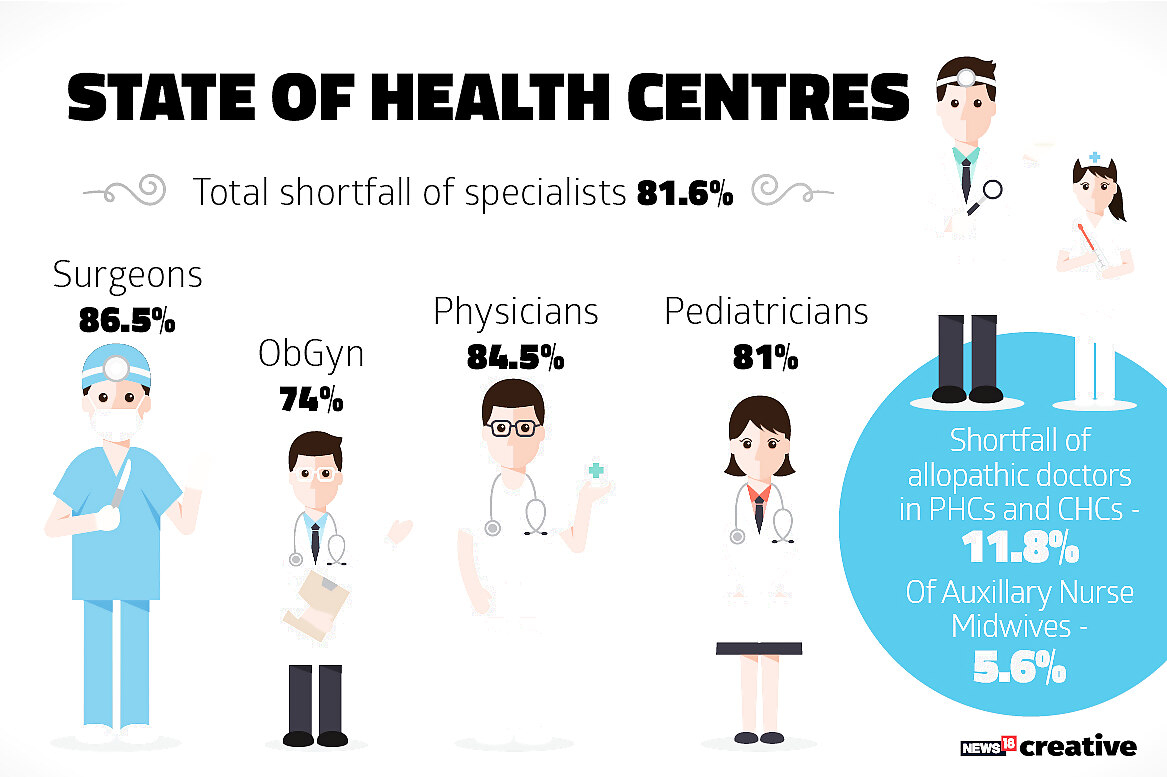

Rural India faces an alarming 81.6 percent shortage of specialists. The number has fallen to 4,156 specialists from 4,192 in 2016.

There is an 86.5 percent shortfall of surgeons, 74 percent of gynaecologists and obstetricians, 84.6 percent of physicians and 81 percent of pediatricians.

This glaring lack of manpower makes redundant the existing CHC infrastructure. With no surgeons to use them, the 4,696 CHCs with functional operating theatres can only exist as empty structures.

The pace of construction clearly outstrips the pace of recruiting and training staff at all levels, be they grassroot workers, lab technicians or allopathic doctors.

States such as Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Gujarat have been noted not only for adding more health centres since 2005, but also shifting them to government-owned buildings.

Uttar Pradesh has increased government buildings to house sub-centres by 11,195 in 12 years.

In the past year, 1,162 new sub-centres, 296 PHCs and 114 CHCs have come up, thanks to Kerala, Gujarat and UP. Yet, there is still a 5.6 percent shortage in the number of ANMs and 11.8 percent shortfall in allopathic doctors needed in sub-centres and PHCs.

There is also a shortfall of 12,511 lab technicians and of 13,194 nursing staff in PHCs and CHCs.

However, the average rural population and the average area these health centres reach has also slightly dipped, though the number of villages one structure serves remains largely the same.

In 2016, a sub-centre, served 5,377 people on an average and a PHC served 32,884.

The 2017 data show the same structures serve 5,337 and 32505 people, respectively.

A CHC which catered to an average of 1,51,316 people in 2016, saw 1,48,248 people in 2017. This decline, even if small, raises questions of whether people are being driven more to the private sector.

Comments

0 comment