views

Developing Your Main Mechanics

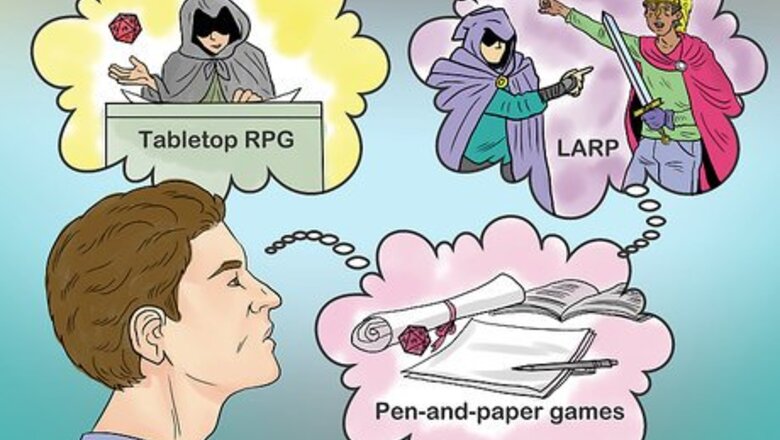

Choose the kind of RPG you'll be making. There are many different varieties of RPG you might decide to create. Common versions include tabletop, or live action role-playing (LARP). You'll need to decide which of these you plan on making before you go any farther on your RPG making journey. Tabletop games are mostly, if not entirely, text based. These games may make use of supplemental materials, like maps or pictures, but rely on written text and spoken descriptions to drive the action of the game. Tabletop RPGs often involve a game leader, frequently called a dungeon master or DM, who designs the scenarios players will deal with and impartially mediates the rules. LARP has players imagine the setting as though it were real life. Players then adopt the persona of a character to complete the tasks involved in the game.

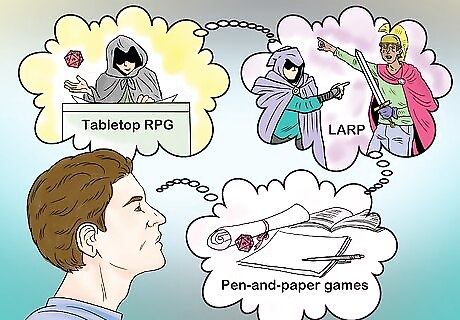

Identify your main stats. A player character's stats gives it a baseline for what it can do and how it will act. Common stats include strength, intelligence, wisdom, charisma, and dexterity. To give you an example of how stats affect characters, a character with high strength but low charisma would likely be powerful in battle but clumsy in diplomatic situations. In many RPGs, the game begins with players creating a character and using a set number of points to invest in different stats. At the start of a game, you might have each player start with 20 stat points to apply to different stat categories. Some popular RPGs use 10 as the baseline for all stats. A 10 rating represents average human ability in the stat category. So 10 strength would be average human strength, 10 intelligence would yield a character of average intelligence, and so on. Additional stat points are usually given to characters as experience is gained over time, through in-game events, or through battles. Experience is usually given in the form of points, with a certain number of points equaling a "level up," which indicates a stat increase. Make sure your stats match up with your character description. For example, a character that's a ranger class will likely be crafty and move silently, so it often has high dexterity. Wizards, on the other hand, rely on their knowledge of magic, so these kinds of characters often have high intelligence.

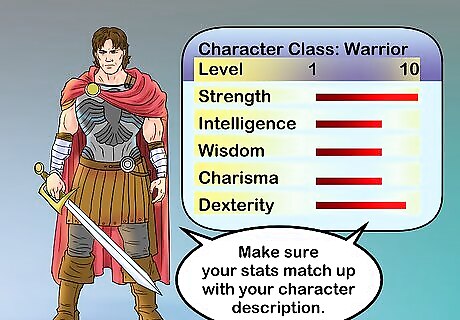

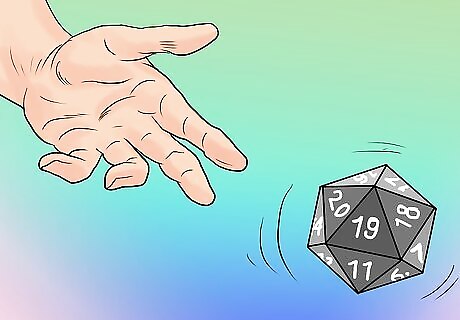

Plan your stat-use mechanic. Now that you have your main stats, you can decide how you'll use them in your game. Some games use a stat-limit check, where tasks will have a rating that character stats will have to match or beat to perform. Other games use a number to represent the difficulty of a task, a dice roll to represent a character's attempt at the action, and stats to provide bonus modifiers to the dice roll. The dice roll/stat modifier mechanic is very common for tabletop RPGs. For example, a player might have to climb a rope. This might have a challenge rating of 10 for a roll of a 20-sided die. This means a player will have to roll a 10 or higher to climb the rope. Since climbing involves dexterity, the player might get bonus points added to their rope climbing roll for having high dexterity. Some games use stats as a way of determining point pools which can be "spent" on actions. For example, for each point of strength, a player might get 4 points of health. These generally decrease when damage is taken from enemies or increase when a restorative, like a health potion, is taken by a character. There are other stat-use mechanics you might come up with for your RPG, or you might combine two common mechanics, like the stat-limit and dice roll/stat modifier mechanics.

Outline the possible character classes. Classes refers to the job or specialty of a character in your RPG. Common classes include warriors, paladins, thieves, rogues, hunters, priests, wizards, and more. Often times, classes are given bonuses for activities related to their class. For example, a warrior would likely receive a bonus for combat maneuvers. Bonuses are usually added to a dice roll to make the outcome of an event more likely. If a warrior needs to roll a 10 or higher on a 20-sided die to accomplish his action, he might get 2 bonus points added to his roll. You can create your own classes for different scenarios in your RPG. Were you playing a futuristic RPG with fantasy elements, you could invent a class like "Technomage" for a class that uses both technology and magic. Some games involve different races which sometimes have special racial attributes. Some common races in RPGs are elves, gnomes, dwarves, humans, orcs, fairies/fey, halflings, and more.

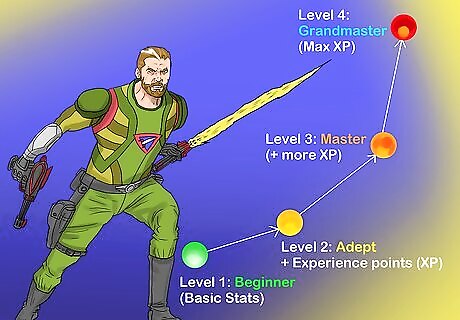

Create a growth scheme. Most RPGs use an experience point growth mechanic. This means that for each foe a character beats in your RPG the character will receive special "experience points." After a certain number of experience points are gained, characters level up and are given additional stat points for the level earned. This represents the growth of their abilities over time. You might base the development of characters around significant events in your RPG. For example, you could award a level up and stat points to player characters following each major battle in your campaign. You might also consider to award stat points to characters after the completion of certain quests or goals.

Determine the style of play. Style of play refers to the structure of gameplay in your RPG. Most RPGs use a turn based structure, where players commit actions one at a time. You might also consider using a timed "free phase," where players can freely commit actions for a set span of time. You can determine order with a roll of a 20-sided die. Have each player roll a die. The highest number will take the first turn, the second highest takes the second turn, and so on. Settle draws with a roll-off. When two or more players roll the same number, have these players roll again amongst themselves. The highest roller in this roll-off will go first, followed by the second highest roller, and so on.

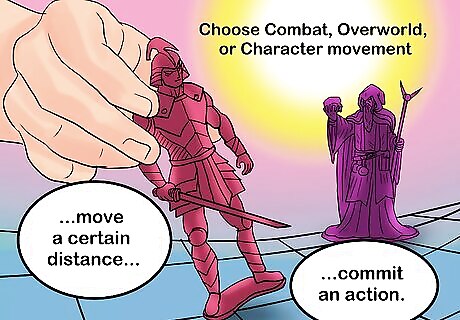

Decide on your mechanic for player movement. Characters in your RPG will have to move through the game environment, so you'll have to decide how they'll do so. Many games divide movement into two phases: combat and overworld. You might make use of these phases or invent your own movement mechanic. Combat movement is usually turn based, with each player character and non-player character each getting a turn. On that turn, each character can generally move a certain distance and commit an action. Movements and action generally depend on things like character class, equipment weight, and character race. Overworld movement usually is the preferred style for long distances. To represent this, many RPGers use figurines moved across a map or blueprint. This phase usually has players move any distance they desire on a turn by turn basis. Character movement is usually determined with regard to weight and class considerations. For example, a character wearing heavy armor will be more encumbered and move more slowly. Physically weak classes, like clerics, wizards, and priests, usually move slower than physically strong classes, like rangers, fighters, and barbarians.

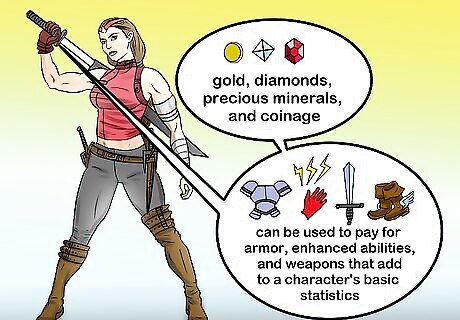

Devise an economy for your RPG. Though not all RPGs will have an economy, characters usually earn or find some kind of currency on fallen foes or from completing quests. This currency can then be traded with non-player characters for items or services. Awarding too much currency to characters can sometimes result in the game becoming imbalanced. Keep this in mind when conceiving your RPG economy. Common forms of currency in RPGs includes gold, diamonds, precious minerals, and coinage.

Write up your main mechanics. It's easy sometimes to skip a step or forget to apply a penalty or bonus modifier. Having a clearly written description of how players are supposed to play the game will help prevent disagreements and establish clear guidelines while playing. You might consider printing a copy of the main mechanics for each player. This way, players can remind themselves of the rules when necessary.

Accounting for Character Condition

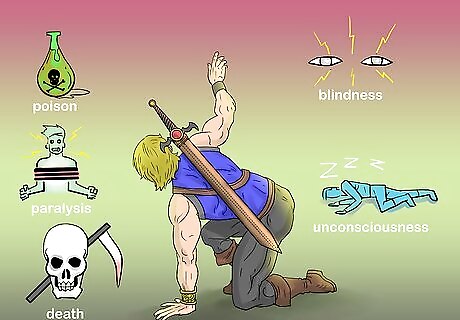

Come up with a list of status effects. Over the course of your adventures, characters may fall ill or be struck with an attack that influences their physical ability. Common varieties of status ailment include poison, paralysis, death, blindness, and unconsciousness. Magic spells are often the cause of status effects. It may be helpful for you to make a list of spells that affect the physical condition of characters. Poisoned or enchanted weapons are another common route status effects are applied to player characters.

Determine the damage and duration of effects, if applicable. Not all status effects result in damage being done, though most wear off over time. In the case of paralysis, a player character might only have to forfeit a turn or two before the effect wears off. Deadly poison, on the other hand, can linger and cause damage over time. You might establish a baseline for the damage of certain effects. For poison, you might decide that weak poison causes 2 damage per turn, medium poison 5 damage, and strong poison 10 damage. You can also decide damage with a roll of the dice. Using poison as the example again, you might roll a four sided die each turn to determine the amount of damage done by the poison. The duration of a status effect might take the form of a standard limit or it could be decided upon with a roll a die. If poison might last anywhere from 1 to 6 turns, you could roll a 6-sided die to determine the length of this effect.

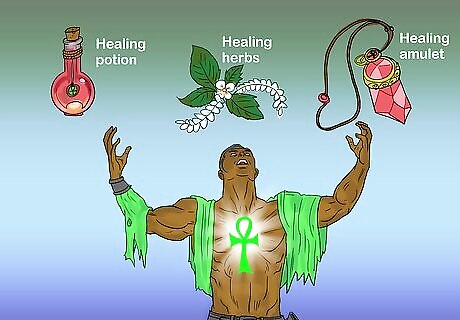

Take the sting out of death with a reviving item. After spending time and effort creating characters for your RPG, it can be discouraging if the character dies and has no means of coming back. Many games use a special reviving item to prevent this from happening. Two common items that revive fallen characters are ankhs and phoenix feathers. To make character death a more serious condition, you might institute a penalty to fallen characters. Characters who have been revived might rise in a weakened state and only be able to move half the distance they would normally.

Make remedies available to characters. Though some status effects may be incurable, in most RPGs there are local remedies, magical potions, and restorative herbs that can heal a character. Rare conditions, like a special kind of disease, will often require a special quest item for the cure to be made. You could make the creation of these remedies a part of your game play. You can do this by requiring characters to hunt for components for these before brewing them up. Common remedies are oftentimes found in the shops of towns and paid for with some kind of currency found or won during the course of the game.

Fleshing out Your RPG

Pinpoint the conflict of your RPG. Many RPGs make use of a villain, also called an antagonist, to give players a clear enemy. However, the conflict of your RPG might be something else entirely, like a natural disaster or a disease outbreak. In either case, conflict will help to motivate your characters to action in your game. Conflict can either be active or passive. An example of active conflict could be something like a chancellor trying to overthrow a king, while a passive conflict might be something like a dam weakening over time and threatening a city.

Draw maps to help with visualization. It can be difficult to imagine a setting without a point of reference. You don't have to be a brilliant artist, but a brief sketch of the dimensions of a setting will help players orient themselves. Many RPG creators will divide maps into two types: overworld and instance. An overworld map is generally a map that depicts the world at large. This might only include a city and the outlying area, but could also include an entire world or continent. An instance map usually establishes the boundaries of a specific player event, like a battle or a room in which a puzzle must be solved. If you're not very artistic, try using simple shapes like squares, circles, and triangles to indicate objects and boundaries of a setting.

Summarize the lore behind your game. In RPGs, lore usually refers to the background information of your game. This might include things like mythology, history, religion, and culture. These things can give your RPG a sense of depth and help you to know how non-player characters, like townspeople, will interact with player characters. Lore can also be useful for developing the conflict in your RPG. For example, there might be an uprising creating chaos in a city in your game. You may want to write out notes for the lore in your RPG to help you keep the details straight while role-playing. For common knowledge lore that player characters should know, you might write up a separate sheet containing this information for players.

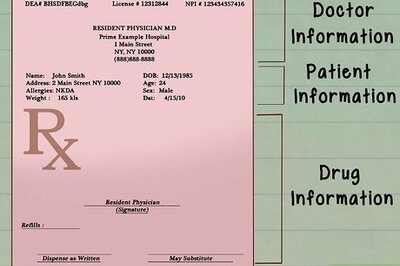

Track character info to keep players honest. The temptation to cheat can be great, especially if you're only 10 gold away from buying that fancy new item. To keep those playing your game honest, you may want a central person, like the game coordinator, to keep notes on players and items for the duration of your game. This kind of in-game bookkeeping is also a good way of keeping your game realistic. If a character has more items than they should be able to carry, that character might deserve a movement penalty for being encumbered.

Comments

0 comment