views

X

Research source

Learning how to tenderize pork will allow you to prepare flavorful, tender dishes with this versatile meat. See Step 1 below to start cooking!

Tenderizing Pork Before Cooking

Use a meat mallet. Cuts of pork are at their toughest when the muscle fibers making up the meat are long and intact. To begin tenderizing the pork before seasoning or cooking it, try breaking up the muscle fibers using a meat mallet (sometimes called a "meat tenderizer"). These usually take the form of either a heavy hammer or mallet with a spiked surface used for beating the meat or a sharp-pronged tool used for stabbing into the meat. The goal is similar with either — simply bash or stab the meat to break up its muscle fibers. If you don't have one of these specialty tools, don't sweat it. You can also use an ordinary fork or even your bare hands to get the same effect if you don't have a mallet handy. Stab, pummel, or mash the meat to break up the muscle fibers and make a more tender dish.

Use a tenderizing marinade. Marinades are a great way to both add flavor to meat and make it more tender. However, not all marinades are created equal — to tenderize pork, your marinade needs to contain either an acid or a tenderizing enzyme. Both of these types of chemicals break down the tightly coiled proteins in meat on the molecular level. However, using too much of either of these substances is a bad idea — too much acid can actually make meat tougher by denaturing its proteins and too much tenderizing enzyme can make meat mushy. Acids like citrus juices, vinegars, and wines are common in many pork marinade recipes. For instance, it's not uncommon to see red wine paired with soy sauce and other ingredients (like brown sugar) as a pork marinade. To avoid the toughening effect that can occur with strongly acidic marinades, you may want to use an acidic dairy product instead — yogurt and buttermilk are only mildly acidic and make great marinade bases for juicy, delicious pork chops. Tenderizing enzymes can be found in the juices of several fruits. For instance, pineapple, which contains the enzyme bromelain, and papaya, which contains the enzyme papain, are both excellent tenderizing ingredients. However, it's important to remember that in high doses, these enzymes can work too well, producing mushy meat.

Brine the pork. Brining is a technique similar to marinating that is especially well-suited to lean cuts of pork (like loin chops). Brining involves soaking your meat in salt water to increase the tenderness and moistness of the final dish. Brines always contain salt and water, but can also include other ingredients for added flavor like apple cider, brown sugar, rosemary, and thyme. Because brining can give the pork a salty taste, generally, you'll want to avoid applying too much salt when eating your pork or applying a salty dry rub after brining. For a great brine recipe, combine 1 gallon (3.8 L) water, 3/4 cup salt, 3/4 cup sugar, and black pepper to taste in a large bowl and stir to dissolve (heating the water in a pot can speed up the dissolving process). Add your pork to the bowl, cover, and refrigerate until you begin cooking. Depending on the type of pork you're cooking, optimal brining times will vary. For instance, pork chops usually require about 12 hours to a full day, whole pork loin roasts can require several days of brining, and tenderloin can be ready in as few as six hours.

Use a commercial meat tenderizer. Another option for tenderizing your pork is to use an artificial meat tenderizer. These meat-tenderizing substances usually come in the form of a powder but are also sometimes available as liquids. Often, the active ingredient in these tenderizers is papain, the natural meat-softening chemical found in papayas. As with papaya, it's important to remember not to over-use meat tenderizer or it's possible to get a piece of meat with an unpleasantly soft texture. Always apply meat tenderizer sparingly. Lightly dampen the surface of your pork with water just before cooking, then sprinkle evenly with about 1 teaspoon of meat tenderizer per pound of meat. Pierce the meat with a fork at roughly ⁄2 inch (1.3 cm) intervals and begin cooking. If your meat tenderizer is labeled as "seasoned", it will usually contain salt — in this case, don't season with extra salt before cooking.

Preparing Tender Pork

Sear the pork, then bake it. When it comes to cooking pork, a wide variety of cooking methods can give juicy, tender results as long as they're carried out properly. For instance, with thin cuts of pork like pork chops or sirloin cutlets, you may want to quickly cook the meat with high surface heat to give it a crisp, savory exterior, then transfer the pork to less-intense dry heat to finish cooking it. For instance, you might sear your pork in a hot pan on the stove (or on the grill), then transfer your pork to the oven (or move it to a cooler area of the grill and close the lid) for the rest of its cooking time. The indirect heat is vital to keeping your pork tender and juicy. While searing is great for giving your pork a delicious exterior "crust", using direct heat to cook your pork completely can easily lead to a tough, over-cooked piece of meat. Indirect heat from an oven or a closed grill, however, gradually cooks the entire piece of meat, leading to a tender, evenly-cooked final product. Since direct heat (like a hot pan) cooks the outside of your meat much quicker than it cooks the inside, you'll generally only need to cook for a minute or two per side to give your entire piece of meat a good searing. However, indirect heat (like from an oven) will take a longer time to cook your pork — usually about 20 minutes per pound.

Braise the pork. One sure-fire way to get a moist, tender piece of pork is to braise it. Braising is a slow, high-moisture cooking method that involves placing the meat in a mixture of liquid (and sometimes solid) ingredients and allowing it to simmer in the mixture for hours. Braising produces extremely moist, tender, and flavorful meat, so it's often the preferred method for cooking somewhat tougher cuts of pork, like shoulder cuts and country-style ribs. In addition, the liquid used for braising can be used as a sauce or gravy, which is handy for pork dishes served with rice or a similar side dish. Though braising times for different pork cuts can vary, in general, you'll want to braise pork for about 30 minutes or so per pound (longer for tough meat or meat with lots of connective tissue). Often, braising recipes call for the meat to be seared or sauteed briefly before braising to give the meat a crispy exterior.

Smoke the pork. Smoking is a very gradual, low-heat cooking method used to give many traditional barbecue dishes a distinct "smoky" flavor. There are a variety of ways to smoke meat, but, in general, most smoking processes involve burning special types of wood (like mesquite) in a closed container so that the meat is slowly cooked from the indirect heat. Over time, the wood gradually transfers its scent and flavor to the meat, leading to pork that's not only moist and juicy, but also has a unique taste that's hard to replicate with other cooking methods. Since smoking can be expensive and time-consuming, it's usually reserved for big pieces of meat that require long cooking times (like brisket, pork shoulder roasts, etc.) and social events like barbecues and cookouts. Smoking is a delicate art form for which many professionals use specialized equipment which can be quite expensive. However, it can also be accomplished with an ordinary barbecue grill. See How to Smoke Meat for a comprehensive guide to smoking meat.

Stew the pork or use a slow-cooker. Using the gradual, moist heat of a stew pot, pressure cooker, or slow cooker can give you pork so tender that you don't need a knife to eat it. Stewing generally involves cooking the meat for long periods of time at low heat while it's submerged in a mixture of liquid and solid ingredients. Often, the meat in the stew is cut into small pieces so that every spoonful contains meat. As with braising, this type of cooking is great for softening up tough pieces of pork or cuts with lots of connective tissue (like shoulder cuts and country-style ribs). Stewing times for pork can vary but are generally comparable to braising times. Slow cookers (like crock pots, etc.) are especially convenient for stewing. Often, with these types of tools, all you need to do is put your ingredients in the cooker, turn it on, and let it cook for several hours without any extra work from you. Note, however, that if you're using vegetables in your stew, these should be added late in the cooking process, as they cook much faster than pork.

Let the meat rest after cooking. If you're trying to get your pork as tender and juicy as possible, don't stop your work when the meat's done! One of the most important, but often overlooked practices in keeping meat moist and tender is the rest period. Regardless of the method you use to cook your pork, after removing it from the heat, let it sit undisturbed for about 10 minutes. You may want to cover it with a piece of foil to help keep it warm. Once the meat has had time to rest, it's ready to be enjoyed! Cutting the meat without letting it rest first makes the meat less moist and tender. When you cook a piece of meat like pork, a great deal of the meat's internal moisture is "squeezed" out of the proteins that make up the meat. Giving the meat a short rest after cooking give the proteins time to re-absorb this moisture. This is why if you cut into a piece of meat that's hot off the grill, you'll see lots of juice immediately run out of the meat, but if you give it a chance to rest first, less juice spills out.

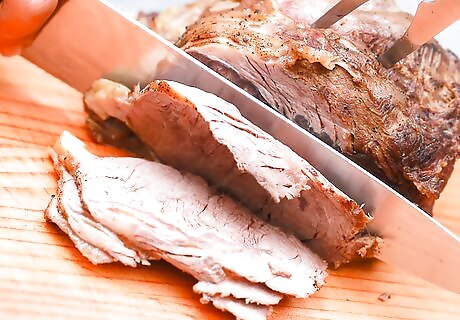

Cut the meat against the grain. If you're trying to get exceptionally tender pork, you should even take the way you cut it into account. To produce the most tender results possible, you'll want to cut the pork in thin slices against the grain of the meat. You'll know you're cutting against the grain if you see the cross-sections of individual fibers in the meat when examining it closely after cutting. Cutting against the grain breaks the muscle fibers into smaller sections one last time before the meat is eaten. You'll never be sorry you took this small extra precaution! With extra-tender cooking methods like braising and stewing, your meat will generally be so soft that you won't need to bother with cutting against the grain. However, for big, thick cuts of pork that have been cooked on the grill or in the oven, you will want to cut against the grain to get your pork as tender as possible before serving it — this is why, at catered events where a large roast is on the menu, the staffer serving it will almost always make thin, diagonal cuts against the meat's grain.

Picking a Tender Cut

Pick a cut from the loin. When it comes to pork terminology , the word "loin" doesn't mean the same thing as it does for humans. The loin is a long strip of meat near the pig's spine that runs the length of the pig's back. In general, cuts of meat from the loin are some of the leanest, most tender cuts on the pig, so they're an excellent choice not only for those looking for soft, juicy pork, but also for a nutritious source of lean protein. Some common loin cuts are: Butterfly chops Sirloin roasts Sirloin cutlets Loin chops Loin roasts

Pick a tenderloin cut. The tenderloin (sometimes called the "pork fillet") is a small subsection of the pig's loin that arguably produces the most tender pork of all. The tenderloin is a long, narrow, lean strip of muscle running along the upper insides of the animal's ribs. Because it is exceptionally juicy, tender, and lean, it's often one of the most expensive cuts of pork. Tenderloin is often sold: On its own In sliced pieces or "medallions" In a wrapped-up "roast"

Pick a rib cut. A pig's rib cage extends from its spine down around to the edges of its belly and offers a variety of delicious, meaty cuts that vary in texture and flavor based on which part of the rib cage they're taken from. Rib cuts from the top of the rib cage (near the pig's spine) can resemble loin meat in that they're naturally somewhat lean, juicy, and tender. Cuts from the lower sections of the ribs (near the pig's belly) can also be quite tender when cooked correctly but are usually fattier and require longer cooking times to reach the perfect level of tenderness. Rib cuts include: Baby back ribs Spareribs Country-style ribs Rib chops

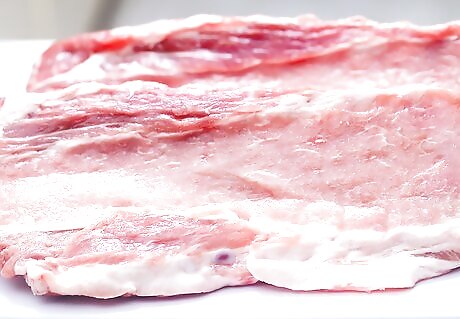

Pick pork belly. As its name implies, pork belly is a very fatty, boneless cut of meat that's taken from the area over a pig's stomach. Many people are familiar with pork belly from eating bacon, which are thin slices of pork belly meat. Because it's so fatty, pork belly usually requires long, slow cooking in the oven or on the grill to become edible, but the results can be deliciously juicy and tender. Beside bacon and related products like pancetta (Italian bacon), pork belly often isn't sold at standard chain grocery stores. You may need to visit a butcher or specialty grocer to get a suitable cut of pork belly for your cooking project.

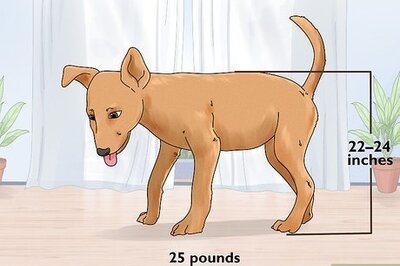

Pick tougher cuts if you're willing to slow-cook. Some of the most tender cuts of pork (especially from the loin) can be expensive. If you're shopping on a budget, you shouldn't feel any need to break the bank just to get deliciously tender pork. In fact, cheaper, tougher cuts (like those from the pig's shoulder region) can usually be made mouth-wateringly tender with slow, low-heat cooking methods. Below are just few cheap cuts of meat that can be made tender if cooked correctly: Picnic shoulder Shoulder roasts Butt steaks Boston butt

Pick less-common tender cuts. If you're willing to experiment, certain less-well known parts of the pig offer the opportunity for tender, juicy pork dishes. These cuts may be somewhat uncommon in modern Western cuisine, but often are central to older recipes or traditional cooking styles. If you feel adventurous, talk to your butcher about getting your hands on these specialty cuts. Just a few non-conventional pork cuts that can be made tender (often with low-temperature slow cooking) are: Cheeks Hocks Trotters/feet Tongue Organs (liver, heart, etc.)

Comments

0 comment