views

X

Trustworthy Source

Cleveland Clinic

Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals

Go to source

Sleep eating is like sleepwalking with food involved; sufferers have no control over the activity and usually no memory of doing it. Thankfully, in the past several years, awareness of and treatment options for SRED have grown significantly. It’s not always easy to quit sleep eating, but it’s worth doing for your health, safety, and peace of mind.

Addressing Sleep Eating

Talk to your doctor. It is hard to pin down just how many people suffer from sleep eating, because many people with the disorder don’t report it to their doctors. Some are too embarrassed to bring it up, and others simply refuse to accept that something so far-fetched — getting up, gorging on junk food, and returning to bed with no memory — can be real. Don’t live in shame, nor in denial — if you suspect sleep eating, tell you doctor. Only a doctor can properly diagnose and treat sleep eating. She will likely ask about your medical history, prior sleep disorders (if any), medication list, recent changes in habits or lifestyle, and other factors that may indicate SRED. Remember: sleep eating is not an imaginary condition, nor is it a personal failure. It is also unlikely to go away on its own. If you suspect it, seek a proper diagnosis and treatment options.

Take a sleep study if recommended. If your doctor suspects that you have SRED, he will likely recommend that you undergo polysomnography — an overnight study at a sleep clinic. This is one of the best current methods to diagnose sleep eating. In a sleep study, numerous probes and monitors will be attached to you in order to track your vital signs and sleep patterns. Even if they do not catch you getting up to sleep eat during the study, this detailed information can indicate a range of sleep habits and conditions that are often present alongside SRED.

Seek behavioral counseling. While there is still much to be learned about the causes of SRED, many cases of sleep eating seem to be linked to excessive stress and/or depression. Before seeing medication alone as your only option, talk to your doctor about the possible benefits of behavioral counseling, possibly in combination with medication to deal with sleep eating. Especially if you have experienced life changes that have increased your stress levels or risk for depression — the end of a long relationship, a death in the family, taking on a new job, quitting smoking or drug abuse, etc. — consider professional counseling as a means to deal with possible triggers for your sleep eating. Along with therapy for depression and stress management, assertiveness training may also benefit some people. Even though sleep eating is not a question of “mind over matter,” learning to become more decisive and in control of oneself does seem to help some people with SRED.

Try medications with promising results. Medication treatments for SRED are still relatively new, which means there are several options but not as much clear evidence of positive results. You may need to work with your doctor and try several options before you find what works best for you. Keep trying, because most people with SRED do benefit from taking medication. First-line treatment is usually is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The recommended dose is between 20–30 mg/day. For some people, anti-convulsant medications such as topiramate (100–300 mg/day) and zonisamide seem to be of great benefit. For others, dopaminergic agents (often used to treat conditions like Parkinson’s disease) such as pramipexole may be used in combination with a low dose of benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) and opiates. Sleeping pills, however, most notably Ambien, seem to increase the likelihood of sleep eating episodes and should be avoided if you have the condition.

Make sleep eating safer instead of trying to forcibly stop it. While you seek out and try out treatment options for your sleep eating, you should also take some practical measures to help protect yourself and others from injury during your episodes. Many sleep eating injuries occur due to falls while traveling between the bedroom and the kitchen, so make sure there is a clear pathway free of trip hazards each evening. Don’t try to restrain yourself in bed, lock yourself in your room, or hide your food. People with SRED are often very resourceful and determined during a sleep eating episode, and will usually achieve their goal in creative and sometimes destructive (or even injurious) ways. Do make sure you have functioning smoke detectors, though, because sleep eaters have been known to leave ovens and stovetops on all night. If you have someone else in the home who can wake up every so often and check for potential injuries or hazards, all the better.

Learning More About Sleep Eating

Don’t view it as an eating disorder. SRED is an eating disorder only in the sense that it involves consuming a large amount of (usually unhealthy) food in a short period of time. It doesn’t seem to have anything to do with hunger, cravings, willpower, or body image, although some people who have made significant dietary changes or who suffer from actual eating disorders like anorexia may also develop SRED. SRED is not linked to daytime eating disturbances such as bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, or anorexia nervosa. Put it this way: sleep eating is an eating disorder in the same way that sleepwalking is an exercise disorder. The activity is a result, not a cause. Sleep eating is a parasomnia, a sleep disorder like sleepwalking, sleep driving, sleep talking, and so on. Sleep eating is not the same as the condition known as “night eating syndrome,” in which a person consumes most of his or her calories after 6 pm and through the night. That condition is caused by a disruption in circadian rhythms, and night eaters are fully aware of what they are doing.

Recognize common triggers. For the most part, sleep eating seems to be triggered by significant lifestyle changes (especially those that increase stress levels) or changes in health or medication status. People with other existing sleep disorders, like sleepwalking, insomnia, restless leg syndrome, and sleep apnea are also more likely to develop SRED. Common triggers of SRED include: depression; quitting smoking, drinking, or drugs; starting or stopping a medication; rapid changes in diet; insomnia; and other sources of stress and anxiety. Sleep eating can occur without any of these triggers being present, however, so don’t discount obvious signs of SRED — unexplained messes, missing food, mystery weight gain, etc. — due to their absence. Women are more likely to suffer from SRED than men.

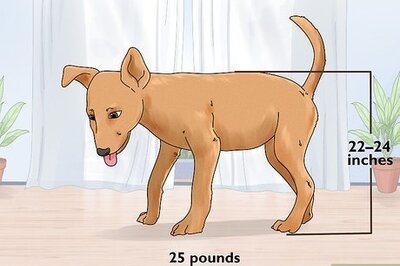

Don’t suffer in silence or shame. Hard data on SRED is hard to come by, but some experts estimate that about one percent of the U.S. population lives with some form of sleep eating. (Roughly ten percent of the population lives with any type of parasomnia sleep disorder.) Young adults are most likely to have SRED, and perhaps up to 80% of sleep eaters are women. A young woman aged 22–29 is the most likely candidate for SRED, for unclear reasons. If you are a sleep eater, it is important to know that you are not alone, you are not to blame, and there is help available. You may benefit from seeking out support groups and interacting with others like you.

Take action for your health and safety. Usually, the negative results of sleep eating include big messes in the kitchen, a depleted pantry, and the addition of unwanted pounds; however, sleep eaters sometimes fall on their way to the kitchen (or back), cause fires or cut themselves trying to prepare food, or break teeth trying to bite into frozen food. They usually prefer sweet or gooey foods (like peanut butter, syrup, or honey), but may also eat raw meat or even non-food items like soap, paper, scouring pads, or (in the worst case) potentially-poisonous household cleaners. Sleep eating is not a joke or just an annoyance, then. It can be potentially dangerous to you and to others in your home. Seek treatment if you suspect SRED.

Comments

0 comment