views

Getting the Necessary Equipment

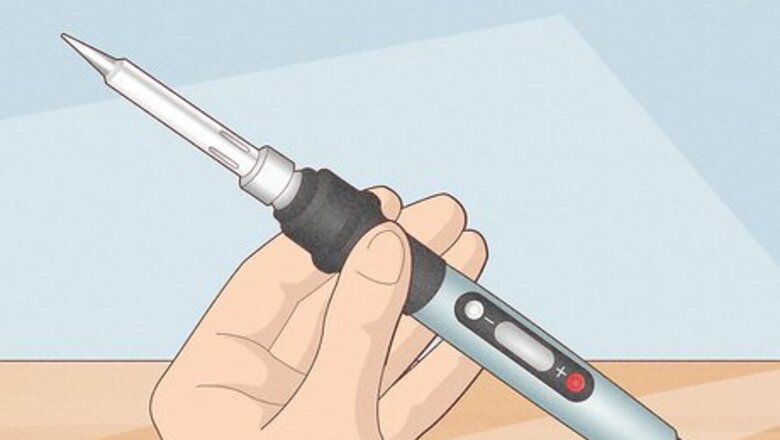

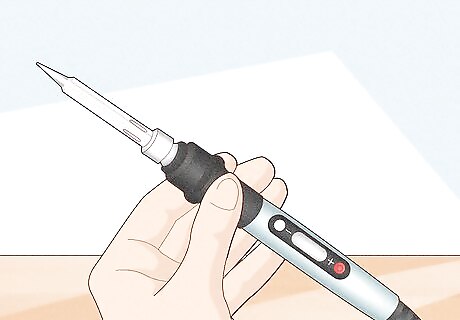

Use a soldering iron with the appropriate heat control. For soldering electrical components into printed circuit boards, the best soldering irons are Electrostatic Discharge (ESD) safe, temperature-controlled, high-power irons. These will let you solder for hours, and are good for complex amateur radio projects. For simple kits, an inexpensive pencil iron will do just fine. Use a fixed power soldering iron, 25-watt for small jobs and 100-watt for larger jobs with heavy cabling. If possible, variable temperature irons are available, which will make for the safest treatment of the boards. The tip temperature can be controlled to suit the size of the job.

Use solder wire of an appropriate alloy. The most common solder alloy used in electronics is 60% tin and 40% lead, sometimes termed 60/40(SN/Pb); the lowest melting temperature is actually 63/37. This is recommended if you are new to soldering, though because of the lead content it is somewhat hazardous. You must use proper ventilation (or a proper respiratory mask), or soldering equipment with a vacuum attachment. Solder that is 60/40 becomes pliable at 361 °F (183 °C) but doesn’t melt until it’s 370 °F (188 °C), which means it may be difficult to work with if you’re a beginner. Instead you can try solder that’s 63/37 since it melts at 361 °F (183 °C). Various lead-free alloys are becoming necessary in recent years under the RoHS regulatory initiative. These require higher soldering temperatures and do not "wet" as well as tin-lead alloys. While they are safer, they are also more confusing. The most common is 96.5% tin to 3.5% silver and will produce a joint with less electrical resistance than a tin-lead alloy. In practice, this is not a reason to use it; the safety issue is the driving factor. You can also get solder that is almost 100% tin, but it is more expensive. Both lead and lead-free formulations are available online at places like solderdirect.com and in various stores in most localities.

Use a flux-cored solder wire for electrical work. Make certain the flux used is electrically compatible. Plumbing solder flux is most definitely not. Flux is a material (rosin or a variation for electrical work) used to prepare surfaces for soldering. Dirt, grease, and so on will interfere with the solder joint and must be removed. Including the flux within the solder wire automatically supplies flux to the surfaces being soldered and is the most sensible choice, though very small, surface mounts or automated soldering may use alternatives. There are several different fluxes commonly available for electrical/electronic work. In order of popularity, these are RMA, RA, and water-soluble fluxes. The more active a flux is, the more important it is that it not remain after soldering, lest continuing chemical action compromise or damage the operation of the electrical or electronic equipment. In particular, water-soluble fluxes must be removed. After soldering, rosins leave a brown, sticky residue which is ideally, non-corrosive and non-conductive. Cleaning can be accomplished with a purpose-formulated rosin removal product, or with isopropyl alcohol. No-clean flux leaves a clear residue after soldering, which is non-corrosive and non-conductive. This flux is designed to be left on the solder joint and surrounding areas. Water-soluble flux usually has a higher activity that leaves a residue which must be cleaned with water. The residue is corrosive and may also damage the board or components if not cleaned correctly after use.

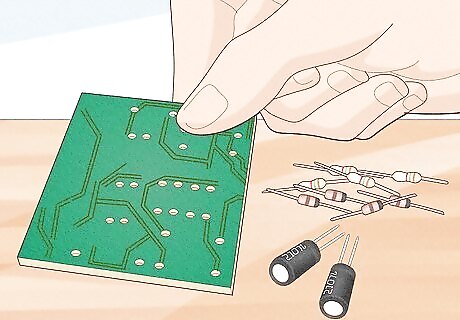

Get the necessary board and components. Mostly, electrical soldering deals with "through-hole" components, whose leads are inserted into holes in printed circuit boards (PCBs) and soldered to a pad of metal plating (a PCB trace) around the hole. The interior of the hole may be "plated through" or not; in the latter case the inserted lead is the electrical connection between traces on the top and bottom of the PCB. Soldering the lead on both sides will commonly be necessary in the last case. Soldering other electrical items, such as wires or lugs, has slightly different techniques, but the general principles of operating the solder and iron are the same. Note however, the lugs and other unsupported soldering points require a firm mechanical connection prior to soldering. A solder joint does NOT provide mechanical strength or resistance to vibration; it only provides a very low resistance electrical connection.

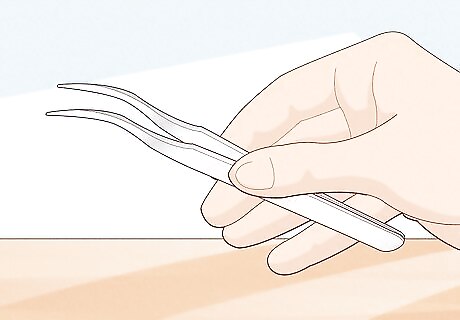

Get a clamp to hold the components. Electrical components are usually quite small, and you'll need tongs, needle-nosed pliers, or tweezers to hold them in place while you operate the soldering iron and negotiate the solder. It can be a balancing act. Some kind of clamp or stand is usually best to hold the board in place while you solder the components.

Soldering the Components

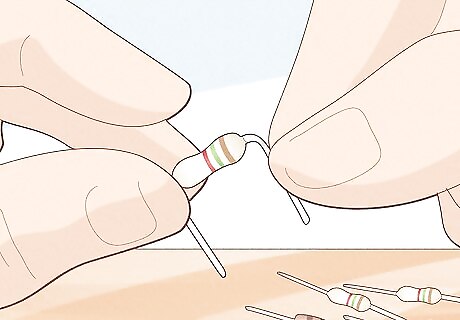

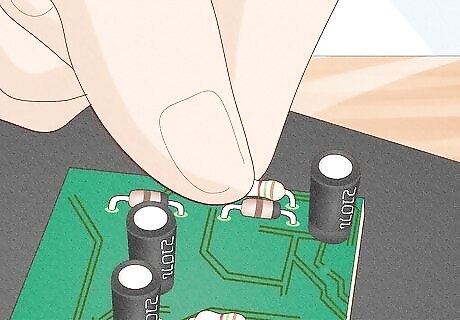

Prepare the components for soldering. Select the correct component by checking its type and value carefully. With resistors, check their color code. Bend leads correctly, if necessary, being careful not to exceed the stress specs (eg, by too sharp a bend), and clinch leads to fit the board.

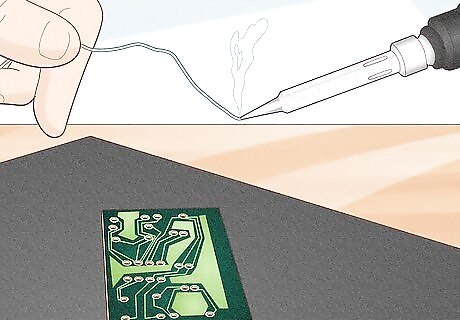

Be extremely careful and solder only in an appropriate environment. Always solder in a well-ventilated area, using breathing and eye protection. Make sure to safely place the iron (using a fireproof stand or holder) when it is on but not in use. Irons can start fires quite easily by burning into your workbench or paper or plastic. Always use a thermal mat or board to protect the area. Leave 7–12 inches (18–30 cm) of space between the electronic components and your face, or solder bits or hot flux may reach your eyes. Safety spectacles are a very sensible precaution. Molten solder may splatter, and is essentially unpredictable.

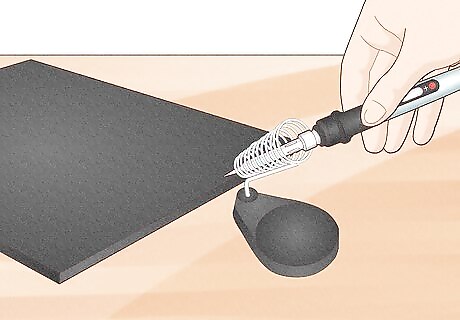

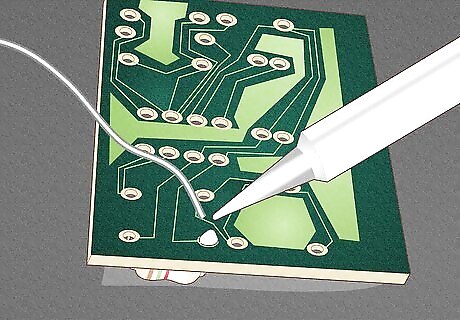

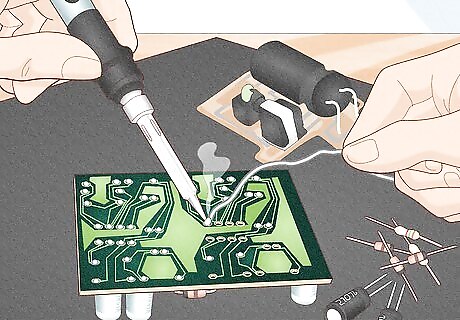

"Tin" the soldering iron tip. Melt a small blob of solder on end of the soldering iron. This process is called tinning and it helps to improve heat flow from the iron to the lead and pad, keeping the board safe from prolonged heat. Carefully place the tip (with the blob) onto the interface of the lead and pad. The tip or blob must touch both the lead and the pad. The tip of the soldering iron should not be touching the nonmetallic area of the PCB, whether fibreglass (very common) or some other material. This area can be damaged by excessive heat.

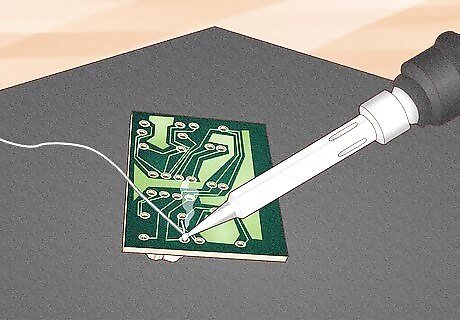

Feed the solder wire onto the interface between the pad and lead. Flux from the solder wire is only active very briefly maximum after melting onto the joint. It is burned off slowly (this is the smoke rising from the joint) and loses its effectiveness as it does so. The component lead and the pad should be heated enough for the solder to melt into the connection point. The molten solder should "cling" to the pad and lead together via surface tension. This is commonly referred to as wetting. If the solder does not melt onto the area, the most likely cause is insufficient heat has been transferred to it, or the surface needs to be cleaned of grease or dirt. The activity of the flux was not sufficient, and external flux may be necessary. Careful cleaning of surfaces prior to soldering may be needed. Use care—sandpaper will generally be too harsh and steel wool (though less mechanically harsh) will add tiny bits of conductive metal—probably leading to unintended shorts and electrical misbehavior.

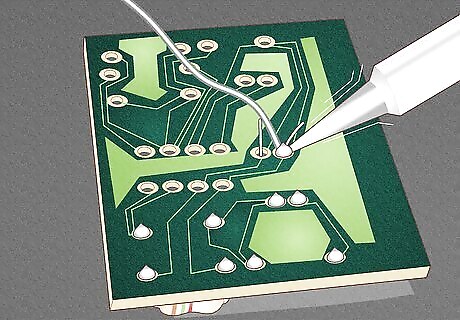

Stop feeding new solder when all the surfaces have been wetted. When the gaps are filled and the surfaces are wet, you should stop adding more solder. No more than a drop or two of solder should be necessary for most joints, though it will vary slightly for different components. The correct amount of solder is determined by: On plated-PCBs, you should stop feeding when a solid concave fillet can be seen around the joint. On non-plated PCBs, you want to stop feeding when the solder forms a flat fillet. Too much solder will form a bulbous joint with a convex shape (ie, blob-like), while too little solder will form an irregular concave joint. Both are visual indications that the solder joint is defective.

Soldering Well

Move quickly. Unfortunately, it's quite easy to damage a component or the board with too much heat. For the most part, however, you can keep the components and the board safe by moving swiftly. A finger on the board nearby may help to notice too much heat. Try to err on the side of irons that are less powerful than you think you might need. A 30-watt iron will be adequate for most electronic work. Practice soldering is a very good idea. If working with a double-sided circuit board check both sides for good solder joints. A good joint will look shiny and cone-shaped. if it looks frosty and dull then it is likely a cold joint.

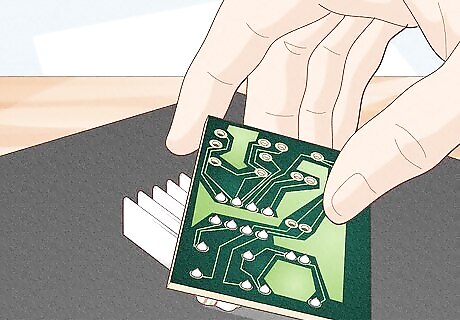

Consider using heat sinks to protect sensitive components. Some components (diodes, transistors, etc.) are quite susceptible to heat damage and require a small aluminum heat-sink clipped on to their leads on the opposite side of the PCB. Small aluminum heat sinks can be purchased through electronics supply houses. Hemostats (small) can also be used.

Learn to recognize when there is enough solder present. After a proper application of solder, the solder will be shiny and not dull. Visible indications are the best way to know if your solder joint is good. The solder must melt onto the surface of the electronic components or PCB traces, rather than the tip of the soldering iron. This way, when the solder cools, it forms a close connection to the surface of the metal. The solder joint should coat the surface of the component evenly, not too much such that it forms a glob, nor too little such that it does not completely coat the surface.

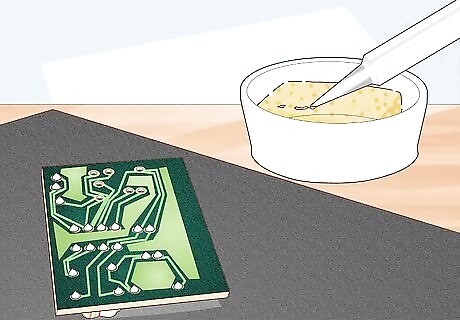

Keep the soldering iron clean. Burnt flux, rosin from the core of the solder, or plastic sheaths from wires may all contaminate the soldering iron tip. Such contaminants prevent the formation of a proper bond between the electronic components. This is undesirable because it raises the electrical resistance and also reduces the mechanical strength of the solder joint. A clean tip is shiny all the way around, without burnt gunk on it. Clean the iron in between each component that you solder. Use a damp sponge or bronze (or brass) wool to clean it thoroughly.

Let the solder cool completely before moving the components. Solder remains soft for a time, and there is little visual indication when the mushy phase ends. This cooling should only a few seconds in most electronic situations; large components have more mass and are both harder to heat sufficiently to solder them and also take much longer to cool to solidify. If the components are too hot to handle, use needle nose pliers, or a tool called helping hands which consists of two alligator clips attached to a little articulated stand. If you watch carefully, the cooling solder will settle right before your eyes.

Practice on junk components. It's important to practice on throwaway stuff before you move straight to trying to solder something important. Get some junk components from an old radio or some such to practice on. Nobody is perfect, not even the professionals. Don't be ashamed to repeat a bit of soldering work (it's officially called rework in the business). It will save you time in troubleshooting later.

Comments

0 comment