views

X

Trustworthy Source

Mayo Clinic

Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals

Go to source

It's a bacterial infection that doesn't respond well to the antibiotics usually used to fight infection. The infection spreads easily, especially in crowded conditions, and can rapidly become a threat to public health. Studies show that the early symptoms are sometimes confused for a harmless spider bite, so it's important to recognize MRSA immediately before it's allowed to spread.[2]

X

Trustworthy Source

Mayo Clinic

Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals

Go to source

Recognizing MRSA

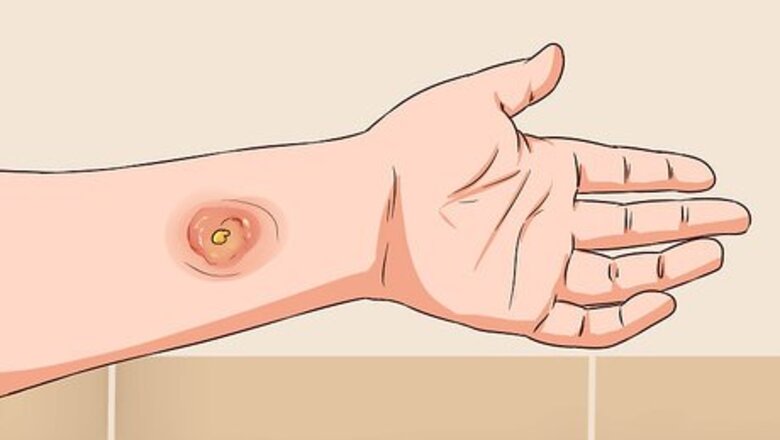

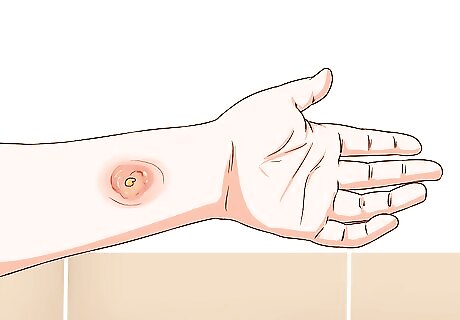

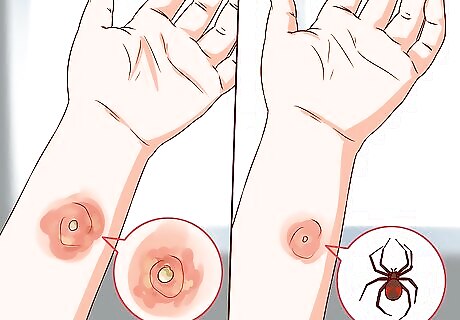

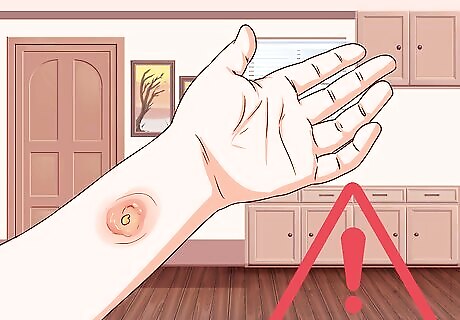

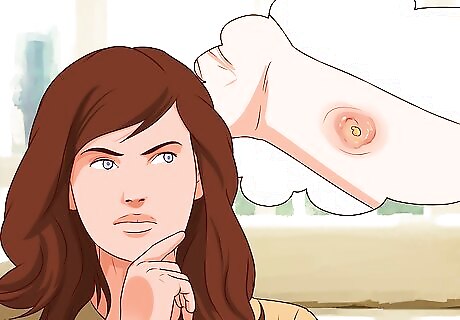

Look for an abscess or boil. The first symptom of MRSA is a raised, pus-filled abscess or boil that's firm to the touch and feels warm. This red blemish may have a “head” like a pimple, and can range in size from 2 to 6 centimeter (0.79 to 2.4 in) or larger. It can appear anywhere on the body, and will be extremely tender. For example, if it's on the buttocks, you likely won't be able to sit from the pain. A skin infection without a boil is less likely to be MRSA, but should still be checked by a doctor. More likely, you need to be treated for a Streptococcus infection or susceptible staph aureus.

Distinguish between MRSA boils and bug bites. The early abscess or boil can look incredibly similar to a simple spider bite. One study showed that 30% of Americans who reported a spider bite were found to actually have MRSA. Especially if you're aware of a MRSA outbreak in your area, err on the side of caution and get tested by a medical professional. In Los Angeles, MRSA outbreaks were so high the public health department raised billboards showing a picture of a MRSA abscess with the text “This is not a spider bite.” Patients didn’t take their antibiotics, believing their doctors were wrong and had misdiagnosed spider bites. Be vigilant for MRSA, and always follow medical advice.

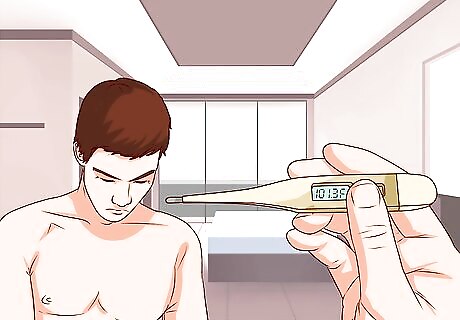

Watch for fever. Though not all patients get a fever, you may get one greater than 100.4°F (38°C). This can be accompanied by chills and nausea.

Be alert for symptoms of sepsis. "Systemic toxicity" is rare, but possible if the MRSA infection is in the skin and soft tissue. While in most cases, patients can bide their time and wait for test results to confirm MRSA, sepsis is life threatening and needs immediate treatment. Symptoms include: Body temperature over 101.3°F (38.5°C) or below 95°F (35°C) Heart rate faster than 90 beats per minute Rapid breathing Swelling (edema) anywhere on the body Altered mental state (disorientation or unconsciousness, for example)

Do not ignore symptoms. In some cases, MRSA might resolve on its own without treatment. The boil may burst on its own, and your immune system may fight off the infection; however, MRSA can be more serious in people with weak immune systems. If the infection worsens, bacteria could make their way into the bloodstream, causing potentially fatal septic shock. Furthermore, the infection is highly contagious, and you could get a lot of other people sick if you neglect your own treatment.

Treating MRSA

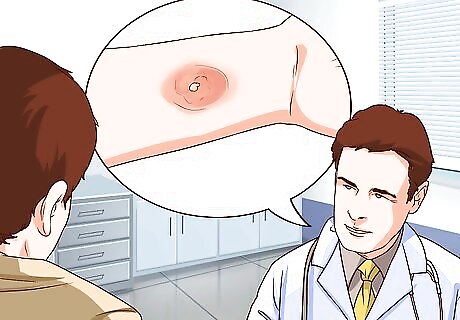

See a doctor for proper diagnosis. Most healthcare providers see many cases each week and should easily be able to diagnose MRSA. The most obvious diagnostic tool is the characteristic boils or abscesses. But for confirmation, the doctor will swab the site of the lesion and a lab will test it for the presence of the MRSA bacteria. However, it takes about 48 hours for the bacteria to grow, rendering immediate testing inaccurate. New molecular tests that can detect MRSA’s DNA in a matter of hours are becoming more widely available.

Use a warm compress. Hopefully, you saw a doctor as soon as you suspected MRSA and caught the infection before it became dangerous. The first, early treatment for MRSA is to press a warm compress against the boil to draw the pus to the surface of the skin. This way, when the doctor cuts the abscess to drain it, she'll be more successful in removing all the pus. Antibiotics may help speed up the process. In some cases, the combination of antibiotics and warm compresses may cause spontaneous draining without actually having to cut the lesion. Soak a clean washcloth in water. Microwave it for about two minutes, or until it's as warm as you can stand without burning your skin. Leave it on the lesion until the cloth cools down. Repeat the process three times per session. Repeat the entire warm compress session four times each day. When the boil has softened up and you can clearly see pus in the center of it, it is ready to be surgically drained by your doctor. Sometimes though, this can make the area worse. The heat pack may be quite painful and your wound may get bigger, redder, and much worse. Discontinue the heat packs and call your doctor if that happens.

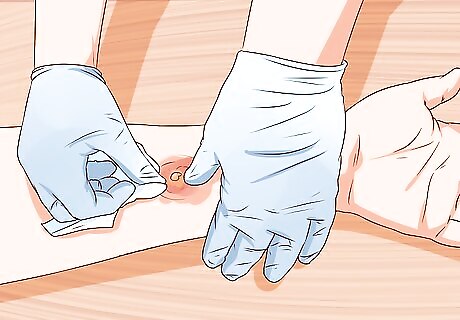

Allow a doctor to drain MRSA lesions. Once you've brought the bacteria-filled pus to the surface of the lesion, the doctor will cut it open and drain the pus out safely. First, she will anesthetize the area with Lidocaine and cleanse it with Betadine. Then, using a scalpel, she will make an incision in the "head" of the lesion and drain it of infectious pus. She will apply pressure all around the lesion, like pushing pus out of a popped zit, to make sure all infectious material is squeezed out. The doctor will send the extracted fluid to a lab to test it for responsiveness to antibiotics. Sometimes, there are honeycomb-like pockets of infections under the skin. These need to be broken up by using a Kelly clamp to hold the skin open while the doctor addresses the infection under the surface. Because MRSA is largely resistant to antibiotics, draining is the most effective way to treat it.

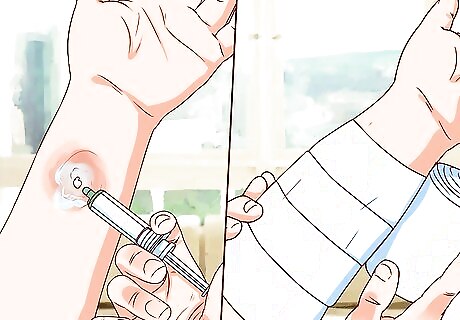

Keep the wound clean. After draining, the doctor will wash out the wound with a needle-less syringe, then pack it tightly with strips of gauze. He'll leave a "wick" out so you can pull the gauze out at home to clean the wound in the same manner every day. Over time (usually about two weeks), the wound will get smaller and smaller until you can't fit gauze in it anymore. Until that happens, though, you should wash out the wound every day.

Take any prescribed antibiotics. Don't pressure your doctor to prescribe antibiotics against her recommendation, as MRSA does not respond well to them. Over-prescribing antibiotics only helps infections become more resistant to treatment; however, there are two approaches to antibiotic treatments in general — for mild and for severe infections. Your doctor may suggest the following: Mild to moderate infection: take one Bactrim DS tablet every 12 hours for two weeks. If you're allergic to it, take 100mg of Doxycycline on the same schedule. Severe infection (IV delivery): Receive 1 gm of Vancomycin through an IV for at least an hour; 600 mg of Linezolid every 12 hours; or 600 mg of Ceftaroline for at least an hour every 12 hours. The infectious disease consultant will determine the length of your IV therapy.

Ridding a Community of MRSA

Educate yourself on MRSA-preventing hygiene. Because MRSA is so infectious, it's important that everyone in the community take be careful about hygiene and prevention, especially when there's a local outbreak. Use lotions and soaps from pump-bottles. Dipping your fingers into a jar of lotion or sharing a bar of soap with others can spread MRSA. Don't share personal items like razors, towels, or hairbrushes. Wash all bed linens at least once a week, and wash towels and washcloths after each use.

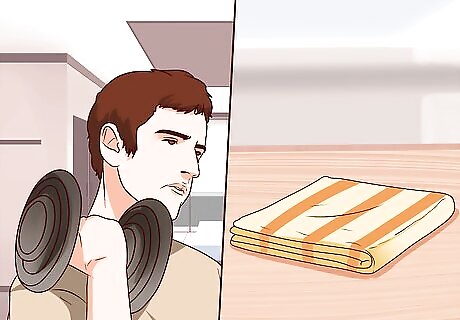

Take extra care in shared or crowded spaces. Because MRSA spreads so easily, you must be especially aware of risks in crowded situations. These might include shared areas of a home or crowded public spaces like nursing homes, hospitals, prisons, and gyms. Though many common areas are regularly disinfected, you never know when the last cleaning was or who may have been in the area before you. It's wise to place a barrier down if you're concerned. For example, bring your own towel to the gym and place it between yourself and the equipment. Wash the towel immediately after use. Make good use of antibacterial wipes and solutions provided by the gym. Disinfect all equipment before and after use. If showering in a shared space, wear flip-flops or plastic shower shoes. You are at increased risk of infection if you have any cuts or have a compromised immune system (like with diabetes).

Use hand sanitizer.Throughout the day, you come into contact with all sorts of shared bacteria. It may be that the person who touched a doorknob before you had MRSA, and touched his nose just before opening the door. It's a good idea to use hand sanitizer throughout the day, especially when in public. Ideally, the sanitizer will contain at least 60% alcohol. Use it at the supermarket, when receiving change from cashiers. Children should use hand sanitizer or wash their hands after playing with other children. Teachers who interact with children should follow the same standard. Whenever you feel you may be exposed to potential infection, use hand sanitizer just to be safe.

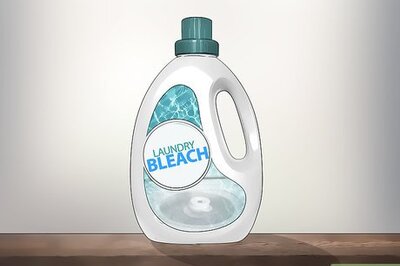

Wash household surfaces with bleach. A diluted bleach solution is effective at fighting the MRSA bug in your home. Incorporate it into your housekeeping routine during community outbreaks to decrease your risk of infection. Always dilute bleach before cleaning with it, as it could discolor your surfaces. Use a 1:4 ratio of bleach to water. For example, add 1 cup of bleach to 4 cups of water to clean your household surfaces.

Don't rely on vitamins or natural therapies. Studies have not been able to show that vitamins and natural therapies can improve our immune systems enough to ward off MRSA. The only study that seemed promising, in which subjects were given "mega-doses" of vitamin B3, had to be disavowed because the dosage itself was unsafe.

Preventing the Spread of MRSA in Hospital Settings

Learn the difference between the types of MRSA. When patients come into the hospital with MRSA, it is "community-acquired." "Hospital-acquired" MRSA is when a patient comes in the hospital for treatment of an unrelated condition, then gets MRSA while there. Hospital-acquired MRSA does not usually affect the skin and soft tissues, so you don't often see community-acquired boils and abscesses. These patients progress quickly to more serious complications. MRSA is a major cause of preventable death and is an epidemic in hospitals across the globe. The infection spreads quickly from patient to patient via unaware hospital staff who don't follow proper infection control procedures.

Protect yourself with gloves. If you work in a medical setting, you absolutely must wear gloves when interacting with patients. But just as important as wearing gloves in the first place is changing gloves in between patients and washing your hands thoroughly each time you change gloves. If you don't change gloves, you may protect yourself from infection while spreading infection from one patient to the next. Infection control protocols vary from ward to ward, even within the same hospital. For example, infection is more prevalent in the intensive care unit (ICU), so contact and isolation precautions are usually stricter. Staff may be required to wear protective gowns and facemasks in addition to gloves.

Wash your hands regularly. This is perhaps the most important practice for preventing the spread of infectious diseases. Gloves can't be worn at all times, so hand washing is the first line of defense against spreading bacteria.

Pre-screen all new patients for MRSA. When you're dealing with patients' body fluids — whether through sneezing or through surgery — it's best to pre-screen for MRSA. Everyone in a crowded hospital setting is both a potential risk and potentially at risk. The test for MRSA is a simple nasal swab that can be analyzed within 15 hours. Screening all new admissions — even those who don’t show symptoms of MRSA — can cut down on the spread of infection. For example, one study showed that about 1/4 of preoperative patients who did not have any symptoms of MRSA were still carrying the bacteria. Screening all patients may not be reasonable within your hospital’s time and budget limits. You might consider screening all surgery patients or those whose fluids staff have to come into contact with. If the patient is found to have MRSA, the staff can decide on a “decolonization” strategy to prevent contamination during the surgery/procedure and transmission to other people in the health care setting.

Isolate patients suspected to have MRSA. The last thing you want in a crowded hospital setting is for an infected patient to come into contact with uninfected patients there for other reasons. If single bed rooms are available, suspected MRSA patients should be isolated there. If that's not possible, MRSA patients should, at the very least, be quarantined into the same area, separate from the uninfected population.

Make sure the hospital is well-staffed. When shifts are understaffed, overworked staff can "burn out" and lose focus. A well-rested nurse is more likely to follow infection control protocols carefully, thus reducing the risk of MRSA spreading through a hospital.

Be vigilant for signs of hospital-acquired MRSA. In hospital settings, patients don't usually have the early abscess symptom. Patients with central venous lines are especially vulnerable to MRSA sepsis, and those on ventilators are at risk of MRSA pneumonia. Both are potentially lethal. MRSA can also appear as a bone infection after knee or hip replacement, or as complication from surgery or wound infection. These can also lead to potentially lethal septic shock.

Follow procedure when placing central venous lines. Whether placing the line or caring for it, lax hygiene standards can contaminate the blood and cause infection. Blood infections can go to the heart and get lodged on the heart valves. This causes "endocarditis," in which a large chunk of infectious material takes hold. This is extremely deadly. Treatment for endocarditis is surgical excision of the heart valve and a six week course of IV antibiotics to sterilize the blood.

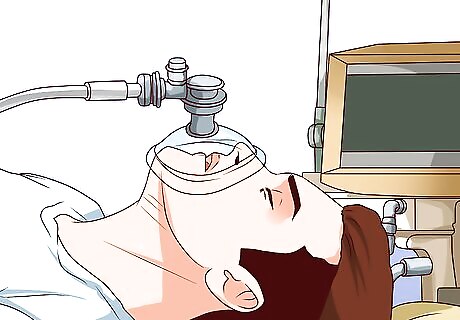

Take the time to maintain hygiene when handling ventilators. Many patients get MRSA pneumonia while on the ventilator. When the staff is inserting or manipulating the breathing tube that goes down the trachea, bacteria can be introduced. In emergency situations, staff may not find the time to properly wash their hands, but you should always make an effort to observe this important step. If there's not time to wash your hands, at least put on a pair of sterile gloves.

Comments

0 comment