views

- Seek treatment for bow legs if you or your child’s legs are misaligned after 8 years old. Bow legs are normal in young children and usually fix themselves.

- Look for symptoms like outwardly curved legs, intoeing, or an awkward walk. Children don’t feel pain, but adults may feel discomfort or develop arthritis.

- Try exercises like squats, yoga, or massage therapy to strengthen your leg muscles and joints. Remember that surgery is the only total cure for adults.

What are bow legs?

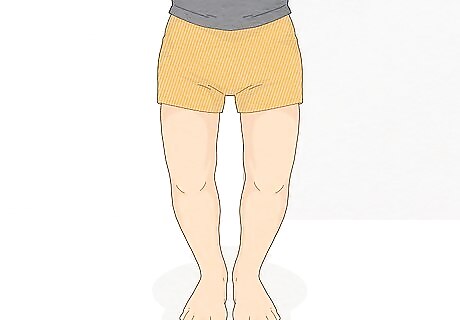

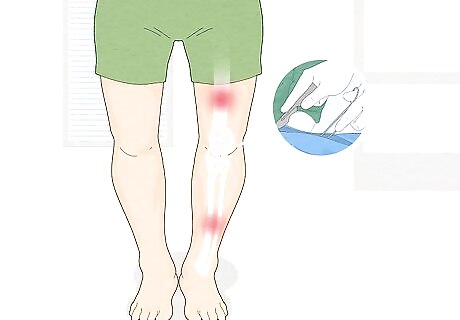

Bow legs is a condition where the legs bend or “bow” out at the knees. This results in a gap between the knees that can’t be closed, even when the ankles and feet are together. The condition is also called bowlegs, bowlegged syndrome, or genu varum.

What causes bow legs?

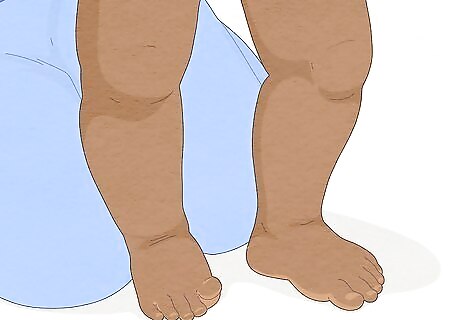

Bow legs are a normal part of a child’s development. Many infants and toddlers go through a bowlegged stage as their skeletal system develops. It isn’t painful or harmful in any way in young children and doesn’t interfere with their mobility. Most children outgrow their bow legs after 18 to 24 months, although some still show curved knees up to age 3.

Infants are born with bow legs because of their position in the womb. The soles of their feet face each other while their tibia and femur bones curve outward, forming a space between their knees. In most cases, the knees move closer together and the leg bones straighten out as soft baby cartilage hardens into weight-supporting bone during the first year of life. By the time most babies begin walking, their legs have straightened.

In some cases, diseases like rickets can cause bow legs. Rickets causes poor growth and fragile bones, leading to bone abnormalities like bow legs. If a child develops rickets under 3 years old, their bow legs will become progressive. Similarly, Blount’s Disease affects the growth plates around the knees—the tibia slows or stops growing on the inside of the knee but grows normally on the outside, causing a bowlegged appearance. Other, less common causes include: Abnormal bone development. Injuries or bone fractures that don’t heal properly. Leg length discrepancy (especially if only one leg is bowed). Lead or fluoride poisoning.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

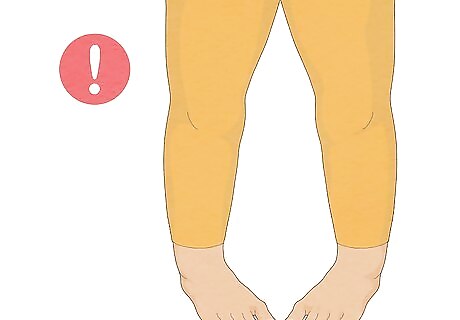

In children, the most visual symptom is the outward curving of the legs. The curving is generally symmetrical in both legs, and the position may cause the child’s toes to point inwards, too (known as intoeing or pigeon-toeing). In rare cases, an awkward walking pattern, clumsiness, or frequent tripping might develop. Bowlegged children don’t feel any pain or discomfort as a symptom.

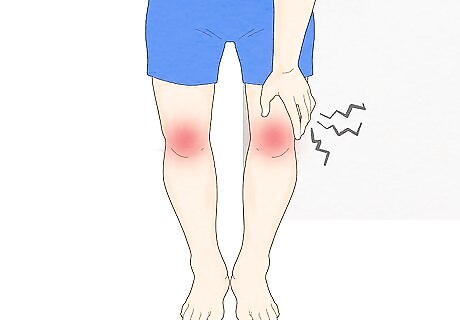

Adults often feel pain as a result of untreated bow legs. In addition to visible symptoms, many adults with the condition feel discomfort on the outside of their knees after years of moving and walking with a misalignment. They may also develop early arthritis in the knees, ankles, or hips from uneven wear and tear on their joints.

An orthopedic doctor diagnoses bow legs with a physical exam. The doctor will check the child’s legs and walk along with their medical history and any other existing health conditions. If the exam is inconclusive, they’ll order a standing-alignment X-ray to look at the leg bones from hip to ankle. In some cases, the doctor will order a blood test to identify or rule out serious or underlying causes for bow legs.

Treating Bow Legs in Children

See an orthopedic specialist if the bowing doesn’t improve by age 8. If you’re worried about your child’s leg alignment, photograph their legs every 6 months to monitor their improvement. See a doctor if the bowing is getting worse or one side is more bowed than the other. If bow legs haven’t naturally corrected themselves by age 7 or 8, ask about treatment to correct the issue before the child's skeleton matures (otherwise, the only corrective option for adult bones is surgery). In most cases, bow legs don’t require intervention. The child’s legs will likely straighten as they grow, typically by the time they’re 3 years old. Children might also develop knock-knees (where the knees bend toward each other) while their legs straighten out, but it usually resolves by age 8.

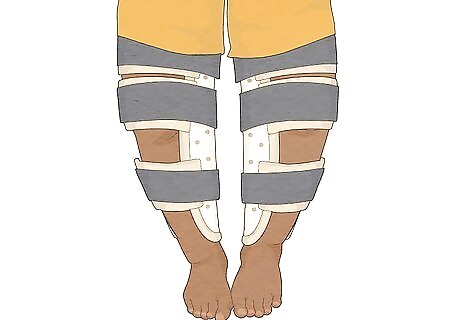

Ask your pediatrician or orthopedic specialist about leg braces. Very young children with severe bowing can wear braces to gently stretch and straighten their legs over time. The braces apply traction at regular intervals throughout the day to pull both ends of the bowed legs away from each other. After the prescribed time, the leg bones will be normally aligned. Braces are usually prescribed when there’s an underlying cause for the bowed legs, like rickets or Blount’s Disease, or if they won’t straighten on their own. Besides braces, there are also special shoes or casts that your child can wear to straighten out their legs.

Consider a vitamin D supplement if they have a deficiency or rickets. Vitamin D is usually prescribed to directly treat rickets in children. As the underlying disease improves and the bones strengthen and grow correctly, the child’s legs will gradually unbow. In some cases, splints or braces will be used to speed up the correction time. If you suspect your child has rickets or a vitamin D deficiency, have them tested to ensure their vitamin D levels are healthy.

Ask about surgical correction for progressive bow legs or Blount’s. A small operation called a “guided correction” may be recommended to cure bow legs if the cause isn’t due to natural growing (physiologic genu varum). This is quite rare, and most children do not need it except in unique circumstances that keep the legs from self-straightening (like Blount’s, rickets, or other diseases). The procedure is minimally invasive and encourages the bowed leg(s) to straighten as your child’s bones and muscles develop.

Non-Surgical Exercises for Adults

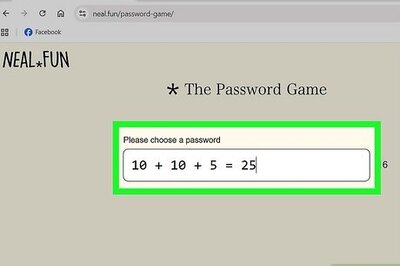

Lift a dumbbell with your feet to strengthen your legs. Lay on your back and bend your knees so your feet are flat on the floor. Place a 10 lb (4.5 kg) dumbbell between your feet and squeeze your legs together to hold it. Extend your legs straight out, keeping the dumbbell secure between your feet, then bend your knees to bring it back until your heels touch your buttocks. Increase the weight or add repetitions as your legs become stronger. Try adding squats and lunges to strengthen your knees specifically. Be mindful of your joints and stop exercising if the motion becomes painful or too tiring.

Strengthen your adductor muscles to better support your bow legs. Located inside your thighs, the adductor muscles balance your pelvis and might improve the bow in your legs. Whenever you sit down, bring your feet, ankles, and knees as close together as possible and hold them to activate your adductors. Also try more intense moves like the following exercise: Lie down on your side. Support your head with one hand and place the other in front of you for balance. Put one leg on top of the other. Take a breath and then exhale as you lift the top leg up into the air. Bring the leg back down to complete one rep. Repeat the exercise on your other side.

Do pilates or yoga to focus on flexibility, mobility, and alignment. Use a yoga strap to help make moves easier on your legs—they may seem difficult when you first start, but you will build strength and endurance the more you practice. Aim to practice yoga or do pilates 1-2 times per day, and gradually increase the length of your workouts as you get more comfortable. Include Cow Face and Forward Bends in your yoga routine. If you prefer pilates, create a routine focused on Ballerina Arms and Roll Ups.

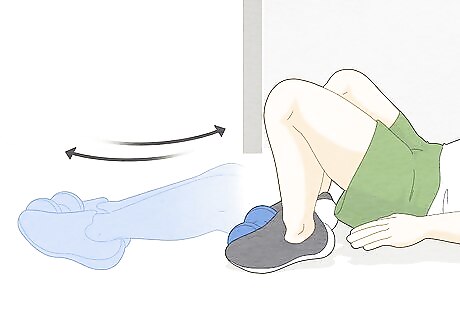

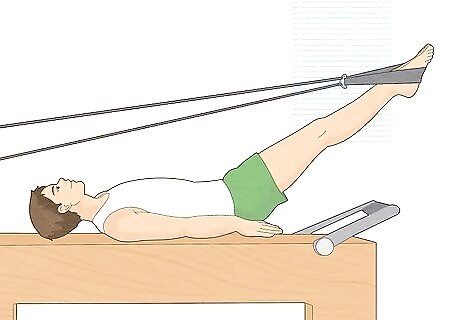

Loosen overly tight leg muscles with massage therapy and knee bends. No matter what exercises you choose to do, pair them with regular massages to treat the overworked muscles caused by bow legs. Work with your massage therapist to target leg muscles, including techniques that move the legs back and forth while you’re on your back. Incorporate knee bends into your therapy for at least 5 minutes per session. To do a knee bend, have the massage therapist push your bent knees into your chest, hold them for a moment, and then pull them forward again.

Remember that exercise cannot change the shape of your bones. Working out, stretching, and doing physical therapy will work wonders for your strength and flexibility. They can even improve joint pain or discomfort, too. Unfortunately, they can’t correct the shape of your bones or completely fix your bow legs. If you’re a skeletally mature adult, the only way to effectively and permanently reshape your legs is through surgery.

Correcting Adult Bow Legs with Surgery

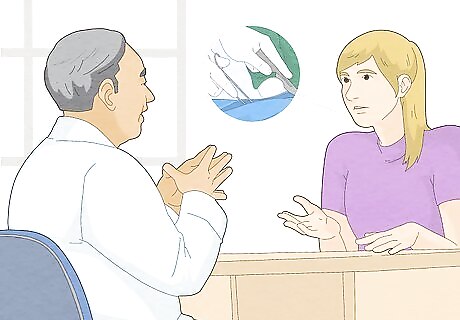

Talk to an orthopedic specialist about corrective surgery for bow legs. Your doctor will order an X-ray to look at the location and severity of the deformity causing bow legs. This will determine the type of surgery you receive. In moderate cases, a plate or rod will be inserted inside your leg to stabilize the bones. In severe cases, external pins will connect your bones to a brace outside your leg to gradually move the bones. This corrective surgery is called an osteotomy. It involves cutting bones to reshape or realign them if they’ve grown irregularly or out of place. Most osteotomies for bow legs reshape the tibia (shinbone) under the knee. Sometimes, the femur (thigh bone) is reshaped above the knee, too. If the bowleggedness makes one leg shorter than the other, your doctor may recommend leg lengthening surgery.

Allow 2 months for complete healing. Follow your surgeon’s orders about how to regain mobility—most people can walk and put weight on their leg within a day of the operation with little to no pain (and in some cases, without crutches or a cast!). Knee pain generally goes away within a few days, but a full recovery can take up to 2 months or longer. Follow up with your doctor as prescribed. Your external frame might be removed ahead of schedule if the bone is strong enough. A typical osteotomy only takes about an hour and most patients spend just one night in the hospital for observation. Osteotomy patients usually gain about 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) in height as a result of the operation.

Aid your recovery with physical therapy and light exercise. Follow your physical therapist’s regimen to aid and speed up the healing process. In addition to guided sessions with a PT, try to stay somewhat active. Try casual swimming or walking—these are low-impact exercises that keep your legs moving and support rehabilitation. As your bones lengthen and your muscles grow stronger, any lingering pain in your hips and knees will fade away.

Comments

0 comment