views

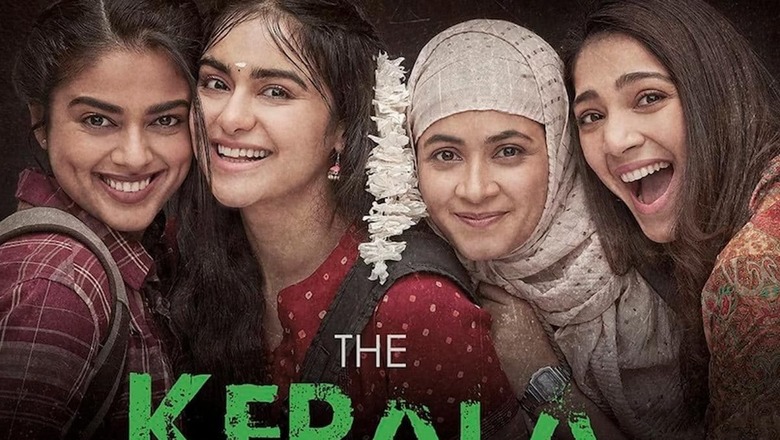

‘The Kerala Story’ has been banned in West Bengal after over a dozen intelligence inputs received by the state secretariat regarding communal instances in the state. “Following the release of the film, the government got reports from some district magistrates and superintendents of police seeking restriction on the movie. The government has its documents ready and these can be presented before the Supreme Court as and when it is required,” said the official.

He further said in many theatres, in and around the prime locations in the city, the audiences were using communal slurs against each other. “The movie is generating hatred for a particular community and there is simmering tension,” he added.

‘The Kerala Story’ directed by Sudipto Sen is based on the ‘radicalisation’ of women in Kerala, and was released on May 5.

West Bengal, which is often seen to be on the edge for political conflicts, has seen a series of censorship in the past, starting from the colonial era to post-Independence.

The state has witnessed a series of communal tensions in the past four to five years, with the latest taking place during the Ram Navami celebrations. The state is also often seen to be at the receiving end owing to its history of partition, an international border with Bangladesh along seven districts.

News18 spoke to multiple experts, senior officers in the state administration, police and other law enforcement agencies to understand the current censorship imposed on ‘The Kerala Story’, and the reasons, background and history behind it.

Playing to the gallery

Anik Dutta, a nationally acclaimed director, told News18 the political parties, “the one, which is ruling the state, and the one, which is at the Centre are playing to the gallery”.

“The content of the movie seems to be a tool of polarisation as I have read and heard a little about it. I have no intention or wish to watch the movie either. But with the politics that has been happening over movies, nowadays, I can say, that the political parties are just playing to the gallery. They are also polarising people to please and appease their respective vote bank. For Bengal, it is about the so-called minority vote bank, which makes the majority vote share of the ruling party here,” said Dutta, whose movie ‘Bhabishyat er Bhoot’ (Ghost of Future), reportedly a political satire, was pulled out of theatres 24 hours after its release in February, 2019.

The government did not clarify why it was taken off screen, and Dutta sought legal intervention.

“I never support censorship. If a movie is bad or ugly or propaganda, let the public reject it. Only CBFC can censor a movie, states cannot. If the government anticipates tension, communal or political, it is their job to handle that. I cannot put my doors and windows closed fearing a thief will enter my house. We have law enforcement agencies for that,” he added.

West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee, who has banned the film in the state, calling it “communal propaganda”, has criticised the Central government’s decision to take down the BBC documentary on Prime Minister Narendra Modi from all platforms in India.

The Centre in February invoked emergency power to restrict the series on Modi across all platforms calling it “a propaganda piece designed to push a particular discredited narrative”.

The issue of censorship becomes particularly sensitive and contentious in nature when a state like West Bengal, which celebrates and takes pride in its liberal cultural ethos, puts a ban on a movie. But history has a different story to tell.

Questions Raised Over Timing of the Release

Kaushik Sen, an actor, director and playwright questioned the timing of the movie. “I have protested, demonstrated against all sorts of bans. In Bengal, many books, theatres were banned, movies were censored by the parties in power. I never supported such bans. But I agree with the decision of the chief minister this time. The Kerala Story is not a movie, not a work of art but a propaganda piece. It has been made to polarise people and trigger communal disharmony. Look at the time of the release. It has been released before elections in states and Panchayat elections in an extremely politically sensitive state like Bengal. This movie is bound to have political and communal ramifications,” said Sen.

“People like us watch movies in expensive theatres, return and write long posts on social media, and at times mobilise people too. But when riots break out in the interior, remote villages, and houses are set on fire, people like us sit at our respective houses and watch them on television. we can’t protect those innocent victims. So, I think the state has taken a pre-emptive action,” he added.

History of Censorship

West Bengal, across decades, has witnessed censorship on books, publications, theatres and movies. The idea of censorship was first introduced through the Vernacular Press Act. It was proposed by Lord Lytton, then viceroy of India in 1878 and the act was intended to prevent the vernacular press from expressing criticism of the British rulers. Over the period of time, many Bengali and Bengal originated English dailies were censored using this act.

Author Sharat Chandra Chattodyapadhyay’s novel ‘Pather Dabi’ was also censored by the British after which he requested Rabindranath Tagore to petition against the ban. The tradition of ban continued in Independent India, with the Congress-led government in the state banning many theatres, mostly by renowned actor-director Utpal Dutta, said a senior historian who does not want to be quoted.

The first movie to be banned in Independent India was ‘Neel Akahser Nichey‘ (under the blue sky) by Mrinal Sen. It was banned in 1959 for its ‘political overtones’.

Towards the end of the Left Front’s rule in Bengal, the state government banned Taslima Nasrin’s book ‘Dwikhandito‘ (divided) in 2005. She was forced to leave the state in 2007 for her controversial writings following a communal riot in the city.

In 2013, the Bengal government did not allow British author Salman Rushdie to visit Kolkata to promote the film adaptation of his novel ‘Midnight’s Children’.

Comments

0 comment