views

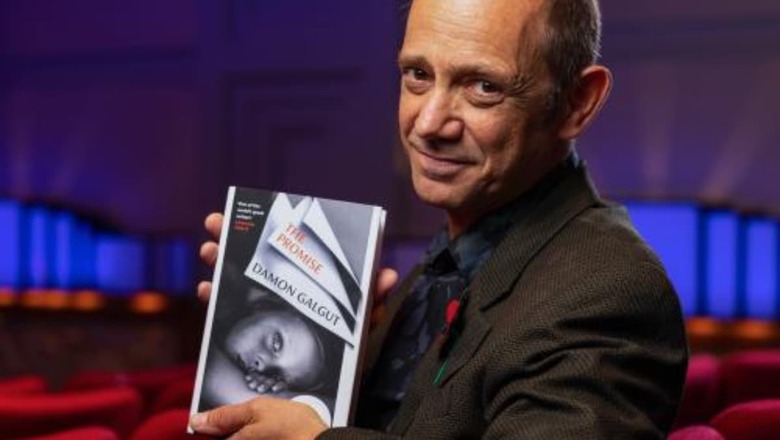

Damon Galgut’s impact on modern-day literature is one that should often be discussed and thanked for. His win at the International Booker Prize 2021 was extremely well received and was definitely celebrated far and wide. There are very few writers who deal with subjects such as racism and injustice in a way as precisely and intricately as he does. He is all set to be speaking at the 17th edition of the Jaipur Literature Festival for the first time since the Booker Prize win. Fans and admirers of his work from all walks of life are very keen on hearing him at the well-curated sessions.

The brilliant author ahead of his JLF sessions sat down with News18 for an exclusive conversation where he spoke about his childhood, career, his nominations at the Booker and then eventually winning it after years and much more.

Excerpts from the interview-

Can you share a bit about your early experiences and what led you to become a writer?

I was very ill as a child and spent a lot of time in hospitals and in sickbeds, being read to by various visitors. My love for books began in that period. It was intense enough to become a need to create them myself. I started very young (and very badly) but I have been at it ever since and have learned a few things as I went.

Who are some of the writers or literary figures that have influenced your work the most?

William Faulkner. Samuel Beckett. Virginia Woolf.

Your novels often explore the landscape and people of South Africa. How does the geography and setting of a place inspire or influence your storytelling?

It matters greatly, in that setting is a presence in the narrative, as significant as any character. I can’t begin writing anything without a strong sense of place. By that, I mean its atmosphere and texture and mood, not its history, necessarily.

“The Good Doctor” and “In a Strange Room” received critical acclaim. Can you discuss the themes and inspirations behind these works?

They’re very different books. The first came out of the optimistic period just after our first democratic elections, when we still naively believed we could re-make our country in an inspiring new image. Something in me was cynical and disbelieving about that project, and I gave voice to the clash between idealism and realism in that novel. In A Strange Room, on the other hand, is about travel and memory and time, and has nothing whatever to do with South Africa. That was part of the appeal of writing it, to be honest: that I could escape history for a little while. But I could only do it by wandering far from my country and shedding any strong markers of identity.

How did it feel to be shortlisted for the Booker Prize twice before finally winning it, and how do you think such recognition has impacted your career?

To be a writer is mostly to be ignored and overlooked. So to be noticed in any significant way is of course a thrill and a blessing. I was happy to be on the shortlist; it brought a certain amount of critical esteem and attention, but not too much. Winning the prize was something like being at the epicentre of a massive explosion. It would be silly to deny that it’s changed everything in my life, in both a good and a bad way. In short, it would be true to say that I’m glad it happened, but I’m also glad it’s behind me.

Do you think people or readers perceive you in a different way now that you are a Booker Prize-winning author?

I don’t know. What do you think?

Coming back to your novels, your writing often delves into questions of identity. How do you approach the exploration of identity in your writing?

I don’t think about it in that way. I just know the question of identity intrigues me. If I sit next to you on a plane and we start a conversation, you would believe almost anything I told you about myself. My job, my past, my circumstances. Without external reference points, there’s nothing to contradict my story. So in one way, our identities are flimsy and arbitrary, things we put on and take off like a hat. On the other hand, we feel ourselves connected deeply to the earth and other people through a profound history, and that’s identity too. So it’s both everything and nothing, heavy and light as air. A mystery, in many ways.

Your characters are often complex and layered. How do you go about developing your characters, and do they draw from real-life experiences or people?

They’re aspects of other people, mixed with aspects of myself. Characters often only become believable when they behave against the grain of their own natures: the selfish person does something generous, and the kind one is momentarily cruel. Human nature is contradictory.

How do you perceive the current state of South African literature, and how has it evolved over the years?

I’m not an academic and not very well-read in South African literature. But I’m aware it has a rich tradition, with talents far in excess of the tiny audience. I suppose it’s true to say that literature has mostly served some purpose here, whether it was to give a civilised voice to the colonial project, or as a form of resistance to white domination. But we’re now in a time when the purpose of novels isn’t clear. What are we resisting, exactly? What are we giving a voice to? The answers are not obvious.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers who are trying to find their voice and navigate the world of literature?

Stop, stop, before it’s too late.

You’ll be speaking at JLF in Feb 2024, what could fans and audiences expect from your session?

I don’t have a clue. Synchronised swimming and interpretive dance are unlikely. I may answer some questions. I’ll try to be interesting.

Can you share any insights into your current or upcoming projects?

Busy working on some short stories. Which I need to get back to right now! Thanks for the chat…

Comments

0 comment