views

Tim Berners-Lee saw the Web as a tool to bring people together. Mostly, it has. But there have been fallouts and bloody battles over control and ownership of its underlying technologies.

Getting Anti-Social

Facebook has been a walled garden: What gets in doesn’t get out. For instance, it has cheerfully helped users import address books from other services, while not allowing other services to access its users’ data. And it doesn’t let search engines in.

Recently, Facebook launched features that seem designed to hit Google where it hurts: An alliance with Microsoft’s Bing search engine, which shows your friends’ movies, books or other items you search and a tie-up with Skype, which directly competes with Google Talk’s voice chat. In early November, a frustrated Google, unable to see what more than 600 million people are doing within Facebook for more than five hours a day, altered its terms of service to state that its data would only be available to services that reciprocated. Guess who got locked out of Gmail address books? And Facebook’s response? A new service: Messages. Though Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg took pains to say it wasn’t an email killer, it is a clear and present danger to Gmail.

Browser Blows

One of the earlier Web wars was over the browser. Netscape Navigator was the clear leader, until Microsoft fired a broadside with its Internet Explorer. By the late 1990s, Netscape was floundering and by 2002, Microsoft had 96 percent of the market.

But, phoenix-like, from the ashes of Navigator rose the open-source Firefox. Released by the Mozilla Foundation in 2004, it had revolutionary features such as tabbed browsing, spell checking and the ability to add in any number of plug-ins. It was an instant hit among the tech savvy. Firefox now has 30 percent of the browser market. Snapping at their heels are Opera, Apple’s Safari (which released a Windows version in 2007) and Google’s Chrome.

Searching for a Fight

Once upon a time, Yahoo was the best way to find things on the Web. Then, as the 20th century drew to a close, Google came, saw and pretty much conquered. In what many consider to be Yahoo’s greatest folly, it contracted Google to power its search results from 2000 till 2004.

Google figured out how to make money from search and its ads began raking in the millions. Yahoo slowly faded from relevance, but, over the last few years, it has been trying for a resurrection. Then Microsoft suddenly woke up to Google’s threat of world domination and launched Bing in 2009. And in a move some called strange, Yahoo sought salvation with Microsoft: Bing now powers Yahoo’s search.

And with Microsoft getting access to Facebook’s 500 million users, thanks to another agreement, Google has a fight on its hands.

Office Space

Microsoft and Google had first locked horns when Google launched Gmail. Microsoft’s Hotmail continues to be the world’s most popular free Web mail service, with Yahoo mail coming in second and Gmail third.

Things got interesting with the launch of Google Docs, which mimicked the MS Office suite, took it online, made collaboration easy, and, yes, free. In 2009, Microsoft released a technical preview of its Office Web Apps, in a strong attempt to keep its flock.

Google then came up with its Cloud Connect feature, which lets users synch MS Office documents with Google Docs. Microsoft replied with Office 365 beta, its own cloud version.

And as Microsoft focuses on its Office suite, Google is readying its next big attack: Chrome OS, a cloud-based operating system that will seek to end Window’s global domination.

For us, of course, it keeps getting better and better.

Flashpoint

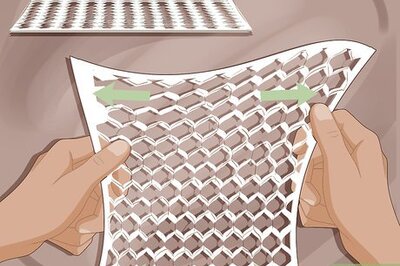

HTML is the glue that holds the Web together. It operates as a sort of common language that all the versions of the world’s varied operating systems and hardware can work with. But it has its limitations when it comes to doing more than the basics. Adobe’s Flash let Web content get past some of those limitations, delivering, for instance, a higher quality of multimedia content.

All good things get abused, though, and sites relying heavily on Flash — some even entrust it with basic navigation, with no flat HTML in sight — can get heavy, resulting in slow downloads.

With handheld devices such as smartphones, bandwidth can be a real issue. This is where Apple steps in. It cut off Flash support from iPhone and iPad. Both devices, instead, used HTML5, an under-development revision of the HTML standard, which includes video playback and other features that formerly worked only with add-ons such as Flash. Apple’s story is that Flash affects battery life, uses a lot of memory and slows its phones, and that it is a closed ecosystem, contrary to the Web’s open nature. Their critics point out caustically that Flash-based apps take business away from Apple’s iTunes store, pointing out that iTunes is pretty much a gated enclave in the first place.

Given the volume of Flash-based Web content out there, this fight’s just begun. A lot will depend on how HTML5 works out.

Getting Smart with Phones

Smartphones are well on their way to becoming ubiquitous and the battle to control the way they work and access the Internet is on. Nokia’s Symbian was the leading operating system (OS) for smartphones until iPhone came along. As Symbian hobbled along, mortally wounded, Google launched its open source Android. After a slow start, Android caught on, particularly with new-gen phone manufacturers, who love that it is free. Developers love it too, since they aren’t limited by the restrictions of Apple’s marketplace. Nokia, in the meantime, is attempting a comeback with its new OS, MeeGo. And Microsoft, whose early attempts at creating OSes for handheld devices sputtered out, has just launched Windows Phone 7 OS, which is getting some very good reviews.

Comments

0 comment