views

In a co-educational college, multiple factors can make women feel uncomfortable. One would assume that an all-women college would then be a haven, but even there the power structure comes into play, making it brutally clear that the ideas of feminism and empowerment in elite universities are exclusionary.

As universities plan to re-open with social distancing norms and having fewer students at a given time, we are reminded of the emotional and the mental distances that spawn on our campuses with regards to the SC/ST/OBC students and their interaction with the privileged. We went through a journey of alienation but also found people like us, who were not necessarily from the same community but had similar experiences. This led to forging solidarities, forming support groups, there was resistance, activation of dead committees for the oppressed and the debut of Bahujan literature in elite college magazine (2017).

Before we discuss this issue of resistance and fight caste biases, it is important to learn that many students and teachers are increasingly building better support systems in university spaces for marginalised students. There is a group of Malayali students support system, active equal opportunity cell in Delhi University colleges like Miranda House, Bahujan student’s group in Lady Shriram College for Women, Ambedkarite organisaion, Muslim students’ group, etc.

Let’s also factor in the non-invincibility of the Left organisations on campus in attaining equality on campuses and fighting for the oppressed categories. The Left organisations on campus are there but barely understand the meaning of experiences and representation. We are making it clear that we are not talking about them.

It’s been more than three years since the two of us graduated from an all-women undergraduate college. However, we are writing about our experiences formally now because of the humiliating discussions on the cut-off yet again. With the first cut-off pegged on 100 percent, it will be helpful to see the difference between the cut-off required from a general category and from an SC/ST/OBC category. Not to forget the socio-economic conditions in which the new normal is setting in – online education among other things.

In general, the problems in the Delhi University colleges for marginalised students can be understood in three forms: First, after we make the cut-off, the unending incidents of discrimination, institutional murders of Dalit-Adivasi students, and the fear of not fitting in scares us so much that we would prefer to drop out from the course all together than go through it, justifying our presence in the elite space. Second, if the oppressed finally get admission to the desired college the possibility of dropping out starts to threaten. They face slurs, reservation debates, language barriers, etc, which push them to decide to let go of the opportunity itself. Third, even if you survive these conditions, the hostility spanning three years lead to alienation, and the feeling of not belonging.

Here, we share our experiences in elite colleges but would like to make it clear the resistance is being led by many first and second generation learners and not just few or the two of us, and we are not claiming to represent a larger group.

Our Experience: The Prejudiced ‘Magic’

The Lady Shriram College is one of the ‘prestigious’ colleges in India, which has been carrying persistent prejudices against the Bahujans and other marginalised students in each of its red bricks. It starts right away from the admission procedure. The initial days of college are embossed on our minds. On the first day of college, the orientation day, we heard our former principal say the perennial phrase i.e. “Magic of LSR.” It took us just half a day on the campus to realise how exclusionary this magic was going to be for some of us.

We stayed in the campus hostel, so we had the maximum exposure to college experience that left distinct memories of our initial days in the hostel. Mornings spent in trying to fit in the classroom of ‘best-ranked’ colleges, and nights spent in justifying our existence in the hostel and the campus during the unwanted reservation debates (angry and tearful sometimes). The discrimination on these campuses is of both forms — statistical and taste-based. Statistical discrimination is perfectly evident in the selection process in all the college societies, students like us just wouldn’t fit anywhere in any one of them (yes, not even the ‘radical’ Dramatic Society!). In the prominent classroom setting our participation was limited to finding a corner or the last bench to overcome the inferiority complex caused by ‘toppers’ who won’t stop talking about how pure Brahmin their family is. This inferiority complex wasn’t our own but it was imposed on us by those who laughed at our Inglis (English), paid too much attention to our choice of clothes than our existence, and were worried so much about ‘their’ seats been taken away by us who didn’t look poor enough as per their standards.

In the hostel, the hostel committee allots single occupancy rooms in the final year only to the top scorers from each department in the hostel, and thus, the line between taste-based and statistical discrimination is blurred. While we were in this condition, it felt more of the latter than the former.

Another important incident to mention is regarding single seat allotment and how insensitive the system is. In our final year during single seat allotment, our friend who scored distinction was allotted a single seater. She was made to shift to a double seater because she could not afford to pay the complete fee. As the first-generation Dalit women from her entire family to enter any university space it was demanded that the authority waive the fee. But despite multiple pleading, mental trauma, and meetings she was forced to vacate her room and shift to a sharing room. And the reason being if they are waiving the fee, she should also compromise a little and not enjoy the benefit of a single seater room. Authority not only made her feel inferior but set an example of structured discrimination.

The first year of not just us, but all those who do not share the privilege of top ten to fifteen percent is spent in fighting the thoughts of dropping out. It starts with casual conversations over the percentage and quickly escalates to unwanted debates, which are more humiliating for us and are a source of entertainment and gratification for them. The target-based debates were organized to demoralise us or to justify their so-called merit. The hatred wasn’t indirect always, the language used by the privileged also included casual caste-ist words and remarks. It is ironic that most of the students in these colleges aren’t from one of the most privileged backgrounds, and yet this unprivileged majority is made to feel unwanted. Like a spectator to the everyday celebration of privilege, inequality, and glorification of caste pride, we applaud in the background- muted with our hands clapping for those for whom we are invisible. Why is it that privilege is rewarded and struggle is criminalized? And we are afraid that with things moving online, classes going on without break, the gap would widen and hence privileged students would flourish at the cost of confidence and sometimes at the cost of the lives of non-privileged ones.

We undertook activities in our college to fight the hegemony and caste-ist environment. And we hope that it would, along with a documentation of our attempts, also give courage to first-generation learners from Dalit-Adivasi background.

Our Response: A Loud Call-Out

Our assertion formally started with the discussion over the topic- “Why reservation is not a poverty alleviation scheme?” It turned out to be one of the first events where we said it out aloud that we won’t let the fellow students make us feel unwanted on the campus. An incident which not only took us with utter dismay and pain became an inevitable reason for us to be even more vocal about caste discrimination.

This was after our brother Rohith Vemula was institutionally murdered (2016). It was like a threshold for us and we couldn’t afford to be quiet anymore. Protests were organized, many shared their experiences of discrimination, and found strength in each other and collectively extended solidarity. But none of this was acceptable to those who have been hiding the caste-ist practices in the name of tradition and institutional practices.

We received neither any sort of institutional support nor informal support from faculty or well-established societies with progressive ideologies. There were numerous incidents of people from student run societies, including college union members, denied to come in support of protests and meetings organized by the oppressed.

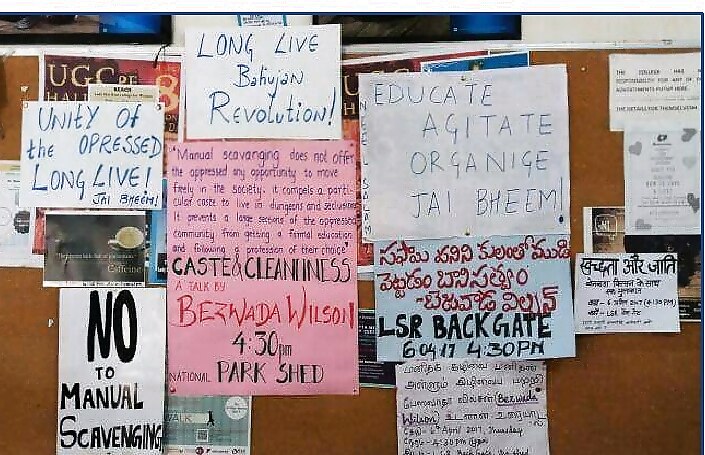

The posters to create awareness were put up in the college but were torn apart, we were summoned by officials, and given warnings too. This was worrying but hardly a deterrent. The events were shifted to a shed at the back gate of the college. It wasn’t as big as the college premises but was extremely inclusive and smashed patriarchy and Brahmanism together. We found that the posters were repeatedly removed, so a better and louder alternative was used- students held posters in hands, wore it over their bodies and walked in the college, and cafe, amphitheater, lawns, classrooms that started echoing with anti-caste slogans.

The space at the back gate extended solidarity to workers struggle, to queer movement, to Safai Karamchari Andolon, and much more. The space wasn’t like the space by any left dominated space, the solidarity here came from experience and empathy and wasn’t just a token/politically correct thing to do.

It’s important to understand that discrimination in the hostel is different from one that happens in the college and classrooms. Staying on campus hostels has advantages which very few students get but it also leaves no space for students to avoid the toxicity. And that is why a lot of our interventions were focused on the hostel.

There used to be an inactive anti-discrimination committee and in fact similar committees meant for marginalised students were either inactive or were in the hold of those who, if not prejudiced, were complacent. We made committee active in the hostel and one of the authors headed the anti-discrimination society.

In one such meeting held in the hostel by the committee it was discussed how certain words/statements used by students were caste-ist slurs. It takes immense courage to share one’s experience and vulnerabilities in public and when in such meetings students realized that they weren’t alone in feeling suffocated that many opened up. In those nights the hostel felt like a safe space, like home, where vulnerabilities are shared, heard and fought together.

One of the authors of this article was also one of the editors of hostel magazine in the year 2017. Bahujan women were encouraged to ink down their experiences. That year, and probably for the first time in the history of the college, the magazine featured a Bahujan student’s work, held resistance and assertion in unlimited forms. Some expressed through poetry, some through art and some narrated the battle they win daily surviving and fighting caste-ism ingrained in campus. Each entry was a blazing voice which existed in silence until then. Experiences were blooming and documented in blue color covered magazines which wrecked the layer of caste pride in red bricked abode.

Way Ahead

The objective of this piece is to help students like us in upcoming batches, those who are vulnerable to such experiences, realise the importance of having our own space and being vocal, and to the stories of assertion without any institutional help.

When the two of us were in this situation, suffocated with invisibilisation and victimisation, we started looking for more like us and voicing our opinions. Our efforts were completely students driven, without institutional help, without any professor listening to us.

We felt happy and proud of what we did. But how important these interventions were for later batches we can’t say that because the changes made at an institutional level have a long-lasting effect. It would be too much to expect from every batch/every generation to fight. One must not be burdened by the thought of waging a big battle, we know that survival in itself is draining in these ‘magical spaces’.The resistance for respect that all of us carried out in the college at student level came at the cost of time for education. We hope that upcoming batches won’t be forced to compromise on their study hours like us, and that is why a strong institutional support system for students with marginalized backgrounds to be in place is much needed. Celebrate every time you survive an institutional onslaught. Let this not be one person’s story, forge solidarities and voice concerns for social justice.

Our movement is a symbol of resistance. Caste may not be a university product but it very well manifests in university spaces. Each one of us carries that ancestral aura within us whenever we shout ‘Jai Bhim’. We gain our inspirations from Savitri mai and Fatima Sheikh, who smashed patriarchy and Brahmanism and became an icon for all of us. Remember Rohith, Anitha, Payal, and all of our brothers and sisters whose names shattered and unveiled caste-ist faces. We are here to carry forward the legacy of edcation, agitation, and organisation.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here

Comments

0 comment