views

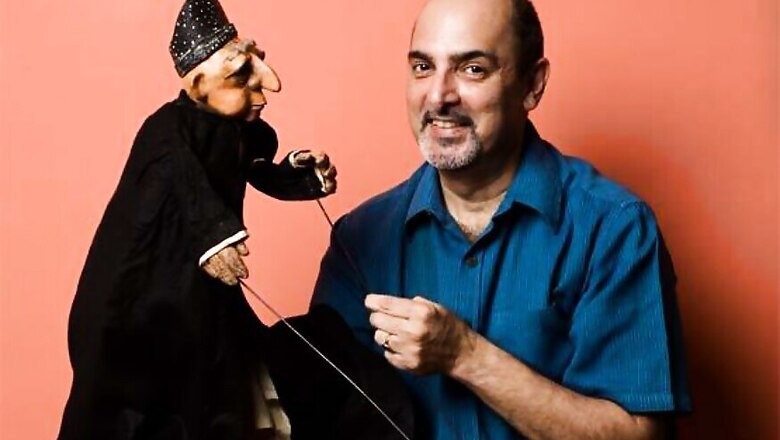

Mumbai: On Sunday morning, the Experimental Theatre at NCPA (National Centre for the Performing Arts) reverberated with hushed giggles of kids, their parents, and grandparents as pioneer puppeteer Dadi Pudumjee's group from The Ishara Puppet Theatre Trust enacted an adaptation of Chatura Rao's beloved children's book, Gone Grandmother (2015) on stage.

The adaptation titled Where Has My Nani Gone?, displayed as a part of NCPA's ADD Art festival, was essentially a puppet show that incorporated several other art forms seamlessly — theatre, dance, music, and movements — to depict a child's effort to grasp loss and understand the sudden death of her grandmother. It also delved into how adults sometimes use obscure lexicon to talk about death to children, like 'woh baghwan ke ghar gaye hai' instead of giving them honesty and helping them deal with their bereavement phase. Although the theme of the play was introspective and serious, there were many light-hearted moments and it ended with resounding applause from young and old audience members.

Pudumjee is obviously used to such appreciation from the audience. After all, for the last four decades, he has done nothing but tell wondrous stories on stage, by lending life, voice, and movements to inanimate objects like puppets, and making them come alive onstage, much to the amazement of his audiences.

Reports claim that puppetry dates back to 500 years before Christ in India, and finds mentions in ancient texts like Srimad Bhagavata where God has been compared to a puppeteer who runs the world by pulling on the strings. Today, unfortunately, puppetry as an art form is by and large neglected.

One of the biggest misconceptions about puppetry in India is that we often think it is just for kids, said Pudumjee. "In my education in Sweden (at Marionette Theatre Institute in Stockholm), I learned two things: the first is that puppetry is not just for kids and, the second is that puppetry is just a means, not an end in itself," said Pudumjee.

The puppeteer in his long career has reinvented the art form many times, by not treating it as an isolated form but something that adapts well with many other art forms, and can work on several mediums. For instance, in the late eighties, Pudumjee started experimenting with traditional puppetry by incorporating dance and movement into it. For an opera piece based on AK Ramanujan's story, ‘A Flowering Tree' that was directed by Vishal Bharadwaj, and staged at Le Chatelet, Paris, Pudumjee's puppetry was complemented by an elaborate dance choreography. The Last March was another big production done in collaboration with the Symphony Orchestra. When Land Becomes Water was adapted from a book by Neeta Premchand on the floods, which was a huge production with shadow puppets. More recently he staged Heer Ke Waris, which was a puppet show for adults, specifically, teens.

"Some puppeteers say that puppetry is dying because of films. But, that's not true," said Pudumjee. "It's how you make the medium and the message meet, or how you use a certain art form that is important. For example, a live theatre performance and a film have their own places. In fact, now you have puppets for television too, like Sesame Street, Gali Gali Sim Sim etcetera. So, there are many new spheres where puppetry can progress," he added.

In India, not many years ago, puppetry was a flourishing, and a diverse form of art with many varied types of puppets originating from different parts of the country. But, unfortunately, now the moment you talk about Indian puppets, what everyone instantly thinks about are Rajasthani Kathputli, lamented the puppeteer.

"The problem is that we only remember Rajasthani kathputli. But, there are shadow puppets in Karnataka, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh. There is a puppetry tradition in Maharashtra's Sawantwadi district. Odisha too has puppetry and Bengal has three to four different techniques — glove puppets, rod, traditional and others," he said.

Ironically, puppetry in India may have evolved from the rural areas — like the legless string puppets (Kundhei) from Odisha, Bommalattam from Tamil Nadu, and the Putul Nautch from Bengal — but today it is surviving mostly in urban areas, where puppeteers are taking the risks to experiment with the form.

"Most modern Indian puppeteers are, as of now, urban-based and perform in cities like Kolkata, Delhi, Ahmedabad, and Chennai," said the puppeteer.

"They come from design and theatre background and aren't traditional puppet makers. Therefore, their inputs and inspirations come from visual arts. They are free to use many different subjects too unlike traditional puppetry which is mostly restricted to epics or folklores. The younger generation of puppeteers is using many different themes and evolving their own techniques," added Pudumjee. He has been trying to facilitate such puppeteers to showcase their talents and for the last 18 years, his Ishara Puppet Theatre Trust has been organising puppet festival in Delhi every year so that more people can learn about puppetry.

In recent times, puppetry is also used for educational purposes (like spreading awareness against HIV, drugs or substance abuse) and psychological analysis. But, unfortunately, despite this parallel surge of interest in this art form, there are no puppetry schools in India. However, the Union Internationale de la Marionnette (UNIMA), an international NGO affiliated to UNESCO where Pudumjee is the world president for many years, has national chapters in different countries, including India, during which short courses of puppetry are taught.

"In the Indian national chapter, UNIMA has been doing mentorship programs, and students workshops to teach Indian traditional and modern puppetry. They also did a three-month-long foundation course for which people came from across India. There were many who applied, and those selected did a very intensive course." said Pudumjee. "But, I am also wondering if there is any need for schools when they have to make their own way?" he asked.

In ancient India, a man like Pudumjee would have been called a ‘Sutradhar’ — the person who holds the strings. For writers, a sutradhar is basically the narrator, who holds the thread of the storyline. But, in puppetry, this individual has far more significance. He is the one without whom the puppet is nothing but a lifeless doll, he is the one who can make the miracle of making lifeless shapes come alive on stage happen. Pudumjee performs this miracle on a regular basis, and for him, it is as simple as moving his fingers.

Comments

0 comment