views

He was a lonely dissenting voice 50 years ago when Tamil Nadu was gripped by the rise of Dravidian ideology. But he managed his voice to be heard through the clever and creative device of humour.

Cho Ramaswamy was in his mid-30s in 1967 when the DMK came to power. After a lacklustre legal career, he had found his moorings in clowning in films and on stage. While he was nothing more than a slapstick comedian in most of his 200 films, he was a clown with a message on stage since he wrote his own theatre scripts numbering 23. His early plays were social satires. With the Dravidian movement capturing power, Cho’s scripts also turned more political, satirising the new breed of Dravidian politicians.

Coming from a traditional Congress family, Cho was an admirer of Rajaji and Kamaraj. As an ardent supporter of free market economy and private sector, he was nearer to Rajaji than Nehru. And when Mrs Indira Gandhi split the Congress and aligned with the DMK in Tamil Nadu in 1969, Cho became the champion of the minority voice supporting Rajaji and Kamaraj. His play Mohammed Bin Thuglak, a satire fantasy of Thuglak becoming the Prime Minister of India, was a spoof of all that Mrs Gandhi was doing then.

Cho launched Tamil’s first political satire magazine on the lines of Baburao Patel’s Mother India, naming it Thuglak. He had a pan-India aspiration and also launched an English version titled Pickwick which flopped and folded. But Thuglak was a roaring success. When the state’s electorate voted in majority for the DMK-Indira Congress, Cho represented the losing minority through his magazine. His no-holds barred satire of the most powerful attracted the readers of the emerging middle and upper middle class. The Karunanidhi government tried to chastise him by intimidation and sometimes legal action. That only increased his popularity with his readers.

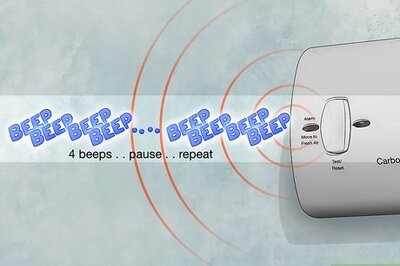

Emergency was Cho’s golden hour. His magazine was heavily pre-censored and he left those pages blank hinting to readers about the heavy-handedness of the powers that be. He utilised even innocuous topics to make political points.

He spared no single leader of the Dravidian movement or the Congress in his satire and earned the confidence of his readers that Cho would spare none. But the popularity of his magazine began to wane in late 80s and early 90s, with the arrival of several Tamil magazines in the genre of investigative journalism.

The rise of the BJP and Hindutva forces revealed another dimension of Cho as their sympathiser. He started dabbling in direct politics as mediator. Despite being a childhood friend of Jayalalithaa, he mediated between the DMK and Moopanar’s Tamil Manila Congress in 1996 to forge an alliance to defeat her. Post 2004, he became soft towards Jayalalithaa and spent all his energy in decrying the DMK and promoting the BJP. He was nominated to the Rajya Sabha between 1999 and 2005.

His credibility as an honest and neutral critic suffered when Prashant Bhushan, his erstwhile supporter, put out documents which alleged that Cho was serving as director in many of Jayalalithaa’s allegedly promoted shell companies and distilleries during the period when she was estranged from her associate Sasikala Natarajan.

Despite his pungent satires on the DMK and its chief M Karunanidhi, Cho maintained a close and cordial friendship with Karunanidhi. He was personally cordial and warm with all those whom he spoofed and criticised. He never hid his views even when he knew they were politically incorrect. He openly expressed his strong rejection of feminism, women holding public offices, rationalism and socialism.

He steadfastly represented the right-wing conservative voice even when it was not popular with the masses. But he was considered a friend to all those who wanted a political and social change thanks to his creative talent of humour.

Gnani Sankaran is a senior Tamil writer and journalist.

Comments

0 comment