views

The May 23 terror attack on the Indian consulate at Herat in western Afghanistan underlines one matter above all: time is running out for India to decide whether it will step up its engagement with the troubled country, and to what extent.

As mentioned in our article, the new government in Delhi will have to tackle the Afghanistan-Pakistan matter whether it wants to or not, and today's attack will just make the clock tick faster. The Pakistan Prime Minister is also faced with a dilemma regarding the invitation to Narendra Modi's swearing-in ceremony. If he accepts, it will be, at least for public consumption, a rebuke to the hawks of Pakistan's military and the ISI. The Herat attack is thus a message to India by the Pakistan establishment not to forget who pulls the Taliban's strings in that country.

India is not a part of the US-led ISAF which has been trying to normalise Afghanistan since 2002, but Indian interests have been attacked consistently over the years. In 2008, the Indian Embassy in Kabul was car bombed, with 58 deaths including an Indian defense attaché, supposed to be a primary target for insurgents. In 2009, the embassy was bombed again, and 17 people died. The group behind it, the Haqqani Network, is seen as particularly close to the ISI. A year later, Indian civilians were targeted in guesthouses, and nearly a dozen were killed. This time the perpetrators, according to Afghan intelligence, were from the LeT.

The question is: should the Indian government step up its intervention in Afghanistan? There are several reasons to support this.

Ever since the days of the anti-Soviet insurgency, India's Afghan policy has been diffident at best and ambivalent at worst. The Afghan national consciousness never forgot that India's engagement, which was at a high in the 1970s, petered off when long-time friend USSR invaded Afghanistan. After the end of the Cold War, India was presented an opportunity to both make amends with the Afghans and pursue an unprecedented opportunity: make a diplomatic breakout in the newly independent republics of Central Asia.

This was frittered away as Pakistan backed the Taliban to the hilt, and barring a few weapon and medicine shipments, and some intelligence inputs to Ahmad Shah Massoud in the Panjshir, India did not make a decisive intervention as the country tore itself to pieces. Meanwhile, Pakistan's military-intelligence complex was virtually running the Talib-overrun parts of Afghanistan.

After 9/11, the American response showed where India had erred: NATO provided massive logistics support to the Tajiks (although Massoud had been assassinated just two days before 9/11) and the Taliban was routed. In theory, that is. What was to be a new beginning has since been bogged down by dogged insurgency.

As things stand today, it is not just a crucial period for India, with a new regime about to assume power, but also for Afghanistan. The ISAF is winding up, but the future looks spectacularly gloomy. In a 2012 Pentagon report on the future of Afghanistan, the process of transition to a stable government in Kabul expressed the hope that the Karzai regime could manage more or less on its own by the end of 2014.

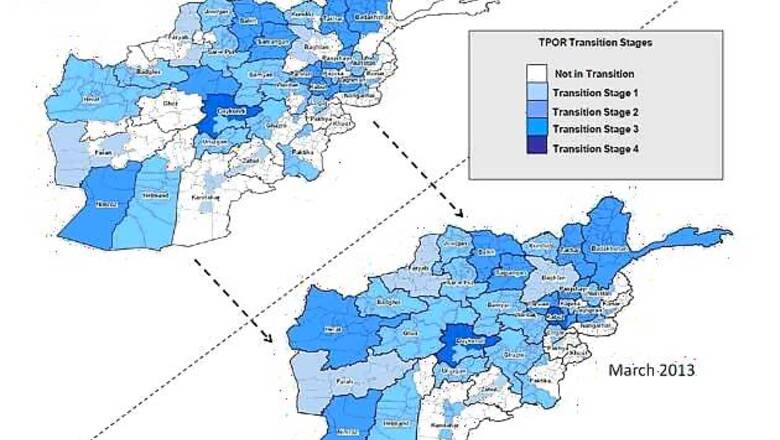

However, the twin threats of low-level Taliban inroads into the vast Afghan hinterland, and poppy cultivation by locals, have never been successfully tackled in the two years since. With a practically non-existent economy and rural infrastructure, impoverished Afghans have been taking to poppy cultivation in greater numbers, filling warlords' and Taliban coffers with drug money. In the 2012 report, only a handful of provinces were listed as on their way to 'transitioning' - Pentagonspeak for transfer of administration to a fully Afghan authority.

The Pentagon report of the year following, 2013, is not for the queasy. The regions in transition are still limited to central Afghanistan. Herat, where the latest attack took place, is partly in transition and mostly dominated by insurgents. The Taliban continues to make inroads and the Afghan government is, to use a term common in similar circumstances, beleaguered.

As things stand, the West can't increase its military and economic engagement there, and an annexure to the 2012 report adds that at current rates of expenditure, the Afghan government will be spending one and half times its total annual income on defense alone for the next decade. There will be no space for any constructive efforts by the Afghans on their own, even if they have the political will to seek this.

In these circumstances, Pakistan will try to regain its lost hold on the country, through its numerous proxies. The two Pentagon reports are very clear that these proxies - The Taliban, the Haqqani Network and the Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin - will continue to scale up their attacks on interests opposed to themselves and Pakistan. India is, naturally, on top of the list.

The new regime in Delhi will therefore have to either abandon Afghanistan entirely after this year, or increase its presence. Mere economic support will not be enough: businesses, construction workers, humanitarian aid groups are all convenient soft targets without a security apparatus to back this up. As a beginning, India needs to rope in the ethnic minorities of Afghanistan, beginning with the Tajiks and Uzbeks. This has cross-border ramifications.

Tajikistan has been friendly towards India, and the Uzbeks wouldn't mind a helping hand since they have come under pressure of Islamist groups beginning with the Taliban's attempt at exporting Chechen fighters to their south in the late 90s.

It is therefore apparent that India needs to commit to Afghanistan for the long term. This will have the twin effect of limiting Pakistan's machinations, and also making a diplomatic breakout into Central Asia. India has for long harboured ambitions of expanding into that region, which would be a crucial countermove to China's maneouvres in Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, India has never pursued this idea beyond a vague level.

The present is as good a time as any to make friends in the region and assure all the players, friends and enemies alike, that we are there to stay. Unlike the West, this will not cause a kneejerk nationalist response in Central Asian Islamic society. The Iranians have been friendly as well, and have no reason to be close to Pakistan, who they view as a Saudi client.

As at every other period in the region's history, this is a time for frantic diplomacy and economic investment, backed by security doctrines which will factor a future Afghanistan left to its own devices by the West. The last time this happened, the Taliban filled the vacuum and Pakistan scored. It is about time for a re-match.

Comments

0 comment