views

- Create pattern-welded Damascus steel by layering or combining different varieties of steel while forging it.

- Etch the pattern-welded steel with ferric acid to bring out the trademark swirling pattern.

- Ancient Damascus steel is unobtainable due to the loss of the type of steel traditionally used to produce it.

What is Damascus Steel?

Wootz Damascus is an ancient type of steel thought to be incredibly strong. Wootz Damascus steel is legendary for its rumored superior sharpness and durability, and was thought in 500 AD to be created in Damascus. Its strength was thanks to the particular kind of iron mined in India, which was high-purity and high in carbon, and also gave the steel its trademark pattern. However the process for forging was said to be lost to history. Wootz Damascus is also sometimes called “crucible Damascus,” which is a reference to how iron ingots were first melted in crucibles along with other materials before they were forged into blades and other items. The term “wootz” may be a misspelling of the Kannada word “wook,” which describes a melted or fused steel.

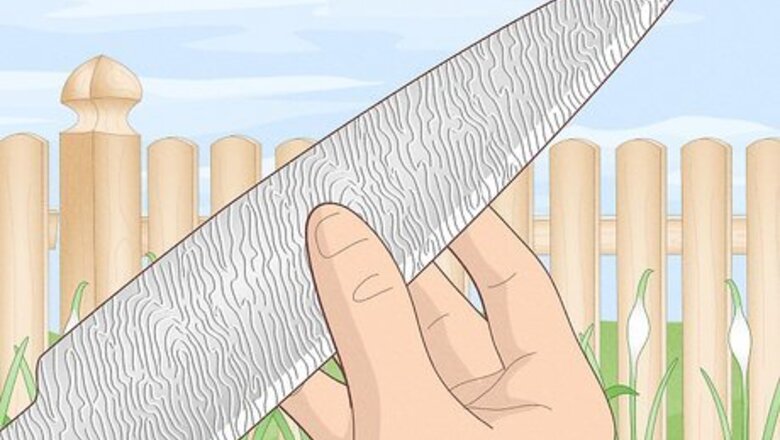

Pattern-welded Damascus steel is made by combining many layers of differently colored steels. This type of Damascus steel is the kind that is commonly made today, and which produces the striking, kaleidoscopic patterns along the surface of high-carbon steel. These patterns are made by repeatedly forging and folding the layers of steel in order to recreate the legendary designs described as appearing in ancient wootz Damascus. Stainless Damascus steel can also be created using stainless steel rather than high-carbon steel.

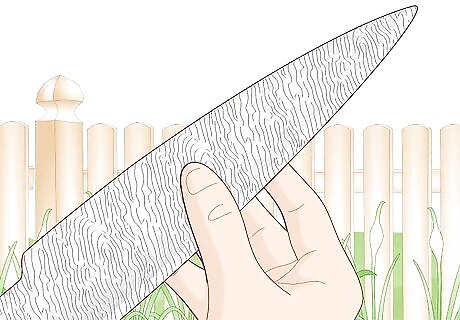

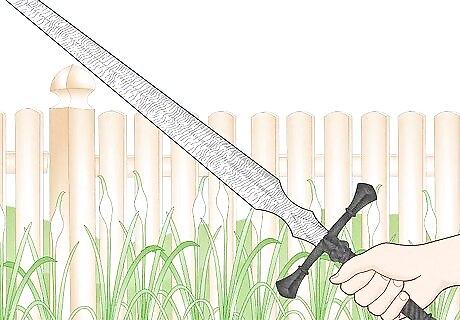

Damascus steel is often used to produce swords and other blades. Because of the sharpness and durability of both types of Damascus steel, this metal is most often used to produce long-lasting and formidable blades. Historically, it was also used to produce body armor.

How to Make Damascus Steel

Gather the specialized materials for forging steel. You’ll need a forge, an anvil and a forging hammer, tongs for handling the metal, a tempering oven, a drill press for etching the metal, an infrared thermometer, a vise to hold the metal while etching, and a welding tool.

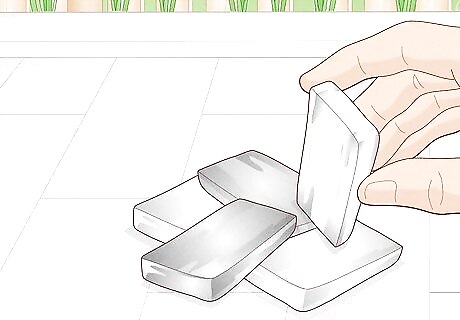

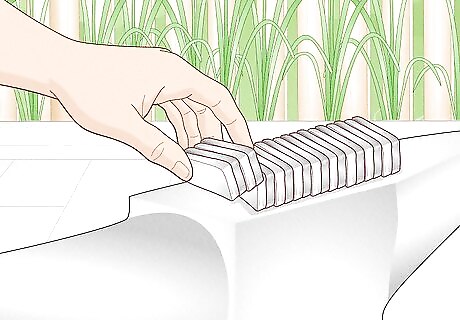

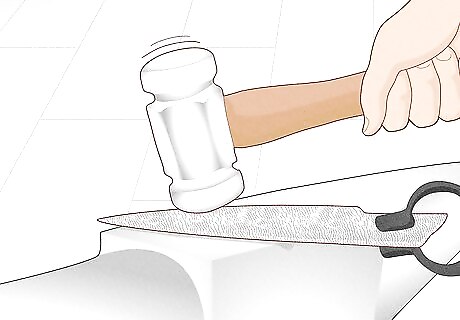

Cut and align the billets. The billets are the various pieces of iron or pre-forged steel melted together to form Damascus steel. Gather these and cut them into the appropriate size for your project. Try to make these piece a big larger than you might need, which will make them easier to hammer. Alternatively, you can melt your metals in a crucible to mingle the ingredients. At this point, you’ll want to make a temporary handle to use while you proceed with forging.

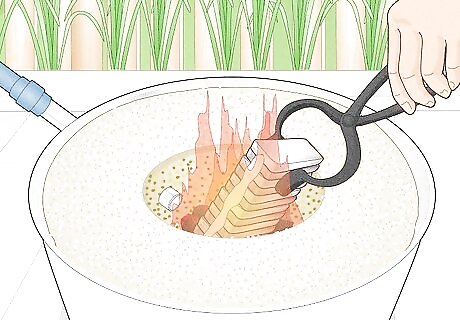

Heat the steel to 1,500–2,000 °F (820–1,090 °C) and hammer it into shape. Place the assembled billets in the forge and hold them there until they begin to glow red. Then, hammer the steel into shape while it’s still hot and glowing. Once the metal has reached the target temperature, remove it from the forge and hammer it into the desired shape. This is a relatively low temperature when it comes to forging, and is needed to keep the various types of metal in the forged steel distinct.

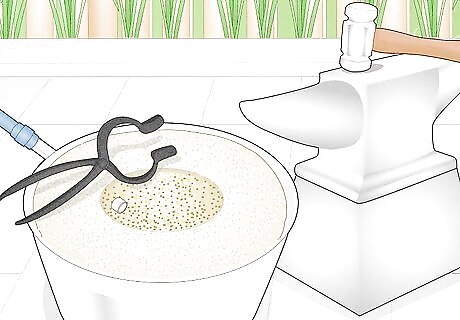

Quench the steel in water or quenching oil 2-3 times. After heating the metal to 1,500–2,000 °F (820–1,090 °C), plunge it into a quenching medium–liquid used to bring down the temperature of forged steel–until it’s back to room temperature. Then, reheat the steal and quench another 2 or 3 times. Quenching heated steel alters its strength and flexibility, and is key to reinforcing metals and making them suitable for use as things like blades.

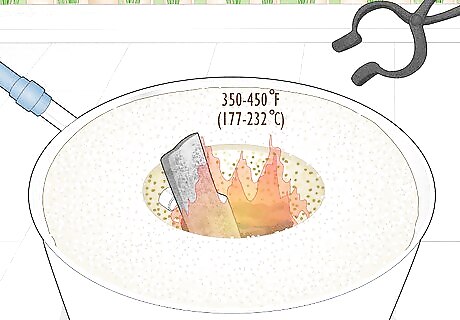

Temper the steel between 350–450 °F (177–232 °C). Hold the steel at this temperature by placing it in a temperature-controlled forge for about one hour, and then let it cool. Repeat this process a few times, until the steel has hardened. Tempering toughens metals and lessens brittleness. It also relieves internal stresses in the metal to prevent breakages, which is key for Damascus steel since it's made of multiple types of metal.

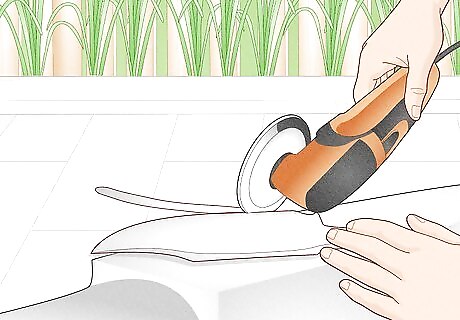

Grind the metal into shape. Use a grinder to cut an edge into your blade, or otherwise shape the steel according to your project. To grind an edge, use a 120-grit belt and let the steel cool in frequent intervals. Increase to a finer belt (220-grit) once the general shape of the blade has been formed. Finally, work up to a 400-600 grit finish over the entire blade.

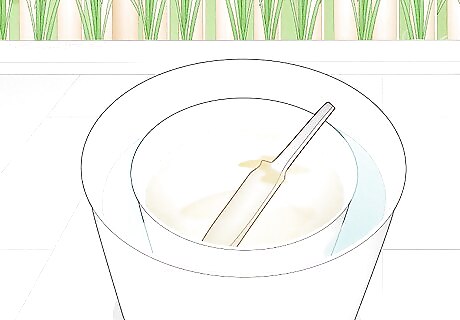

Etch the steel using ferric acid. Dilute ferric acid to a 50:50 ratio with distilled water, then heat to 70–100 °F (21–38 °C) by placing the container of acid into a warm water bath. Once prepared, plunge the forged steel into the solution, and leave the steel immersed for 10-15 minutes in order to etch the steel.

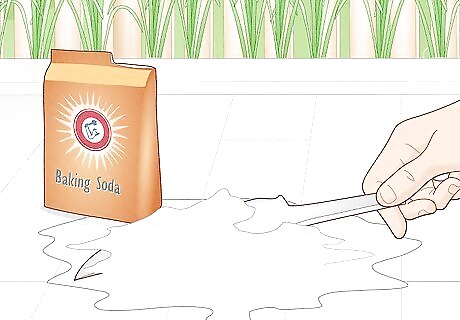

Neutralize the steel in baking soda. Once etched, immerse the steel in baking for 5 minutes in order to neutralize the acid. Then remove the steel from the baking soda and rub it down with alcohol and gently dab it dry with a clean rag. Repeat the acid-and-baking soda process if you’d like a deeper, more striking etch.

History of Damascus Steel

Both pattern- and wootz-Damascus steel were first produced sometime before 500 AD. Wootz Damascus originated in the Middle East, and was made with particular types of iron ingots (called “wootz ingots”) sourced from India. The iron ingots were shipped to Damascus, Syria, where they were used to forge blades and body armor.

Damascus steel weapons were encountered by Crusaders in the 11th century. The items made from Damascus steel were coveted by Europeans for their strength, sharpness, and signature “damask” pattern that appeared on their surfaces. Europeans created a number of myths about the production of Damascus steel. Because the Damascus metalworkers were secretive about their methods, rumors were spread about the forging processes of the steel. Some said it was magical because it was quenched in “dragon blood,” and other strange liquids.

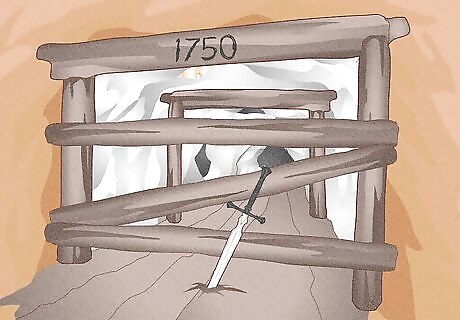

Wootz Damascus may have disappeared when Indian mines were exhausted. At some point, the materials needed to make wootz Damascus became inaccessible to metalworkers, and production of wootz Damascus steel stopped around 1750. This is why we know relatively little about the material today. You can see many examples of ancient Damscus-steel weapons and armor in a number of museums, and research on these items is ongoing to study the makeup and forging methods of wootz Damascus steel.

Comments

0 comment