views

Getting Started

Select a material for shaping. The easiest materials to start with include chert, flint (a subtype of chert), and obsidian. These all leave smooth surfaces behind when fractured, require comparatively little force to chip, and usually have a uniform, fine grain. Once you've made a few small objects with these, you can experiment with materials that are a bit more difficult to work with, including basalt, lab-manufactured quartz, glass from the bottom of a wine bottle, and some types of porcelain. Tap the material with a hard object. Generally speaking, the higher the pitch you hear, the better it is for knapping. You can find many of these on eBay, or you can look for the right stones in nature if you have a geological guide to your local area. However, do not disturb piles of stone or stone surrounded by flakes and fragments. These are part of the archaeological record and should be left undisturbed.

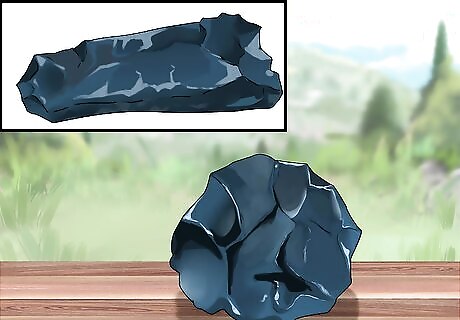

Choose a suitable piece. Select a stone that has few, if any, large cracks, fissures, bubbles, significant grain, noticeable inclusions (traces of other minerals), or other irregularities which would likely cause it to break or flake off in ways contrary to the shape you are trying to achieve. When it comes to size and shape, you have two options: A flake is ready to be turned into an arrowhead or other tool. These are slightly convex, and relatively small. A core is a large stone, which you can break to create flakes. If you're hunting on your own, you'll likely have to start with one of these. Note that the term "preform" can refer to either of the above stages. The term means a material that has not yet been formed into a tool.

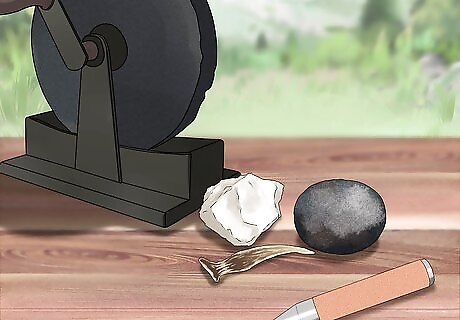

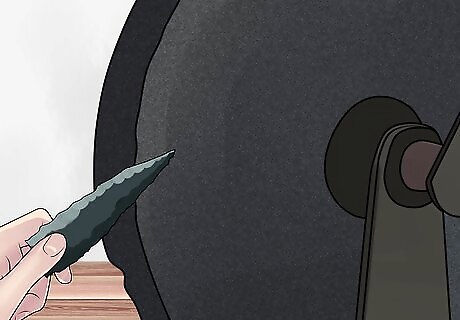

Gather your flintknapping tools. If you are working with a ready-made flake, all you need is a pressure flaker, typically an antler tine or copper nail set in a wooden handle. If you have a core, you'll also need a more powerful striking tool, either a cylindrical "billet" or simply a dense, round stone that fits your hand (a hammerstone). A piece of limestone or other stone softer than your material, or an old grinding wheel, is also required if you are starting with a core. See the Tips section below for more information on choosing billets and pressure flakers. A pressure flaker tool at least 1 ft (0.3 m) long will give you more control and reduce the risk of "tennis elbow" from repeated use. A smaller one may be easier to use for your first attempt, however.

Wear protective clothing. You'll be handling sharp, broken stone, and sending fragments of it flying. Goggles and thick, long pants are essential. Wear long sleeves and gloves as well, or expect to receive cuts and scrapes. A piece of leather to drape over your leg, and a smaller one to hold your materials with, are recommended.

Work in ventilated areas. Always work outdoors in an open area, away from structure, or in a ventilated area with a high-powered fan constantly blowing away from your face. Stone dust is extremely sharp and can damage lungs and eyes over time, especially in an area of still air where it creates clouds of dust. Work over a tarp or cloth, so you can gather up and discard the fragments once you are done. Fragments left on the ground can cut feet.

Sit comfortably. You can knap on a table or bench, of course, but traditionally knapping is done sitting cross-legged, with the stone in one hand in one's lap. This method can be difficult for beginners. Experiment to find out which sitting position gives you the most control, especially with pressure flaking. If you have a core, continue on to the next step, "create a flat platform," or to "use direct percussion" below that if you already have a flat side on your core. If you have a flake, continue on to "abrade the edge" below, or directly to the section on pressure flaking if you bought a ready-made flake with a thick, dull edge. Large, heavy stones may require a table or a large, flat stone – but better yet, pick something smaller for your first project.

Preparing the Material

Create a flat platform on the core (if necessary). If your core is round or has an irregular surface, you'll need to strike it with a hammerstone to create a relatively flat "platform" to start with. The stone will fracture at roughly a 50º angle from the direction of impact, so for a round rock you'll want to tilt the core to about 40º and strike straight downward. The platform must be next to a side that narrows inward. You won't be able to use any side that bulges outward from the platform, or goes straight down at a 90º angle.

Use direct percussion to create flakes (if necessary). If you are using a core, once you have a flat platform, use your hammerstone or billet to strike off flakes, or thin, relatively flat pieces you can turn into tools. Always remember that the stone fractures at a 50º from the point of impact. To use this to your advantage, tilt the core so the platform is at a 40º angle from the vertical. Strike the lower end of the platform with the tool, hitting it with a glancing blow that carries on past the point. You may need to repeat this several times around the platform, until you get a piece that is mostly flat, and a fair amount larger than the tool you want to make. If the material splits into three pieces, or the platform crumbles around the blow, the angle is probably too small (the blow is too direct). If you're only getting tiny chips, the angle is probably too large (the blow is too glancing).

Trim the flake shape. Unless you were lucky enough to get a perfect triangular or rectangular flake, you'll probably need to break it further. Do this using the same direct percussion technique, until you have a piece a bit larger than what you want to end up with, and with no concave "bites" taken out of the edge.

Abrade the edge of the flake. Abrading is one of the most important processes in flint knapping. A newly struck flake typically has thin, fragile areas around the edge, which need to be ground down to a dull, thicker edge so it can withstand the impact of the tool. To accomplish this, grind the edge of your flake in a sawing motion against another flattish sort of stone of slightly lesser hardness. Old grinding wheels work well for this, or any smooth hunk of limestone. If grooves appear in the tool you are grinding with, this is a good sign, since it means the tool is softer than the flake. Once the fragile edges have chipped off or been ground down, you'll have a dependable platform able to take the extreme rigors of lithic engineering.

Pressure Flaking

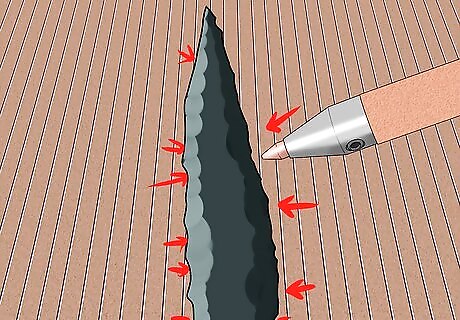

Understand pressure flaking. After your flake is reduced so that it is about seven or eight times wider than it is thick (for a larger project), it's time to begin pressure flaking. Pressure flaking is achieved by placing your work into a fold of thick leather. Hold this in your hand, place a pointed tool (the pressure flaker) on the edge of the stone, and apply an inward pressure to the tool, focusing energy toward the inner area of the flake, usually at a more severe angle of about 45º. You don't want to drive the tool directly toward the center, or it could shatter. The goal is to apply pressure until the tool removes a small, thin piece from the stone, leaving a shallow scalloped shape behind. Remember, you are working from the edge inward. This is the opposite direction of the force you used in direct percussion. Never push down on a concave portion of the edge, or the piece could break. You may need to skip some areas or guide the pressure flaker around it from both directions in order to shape that section to a more usable area.

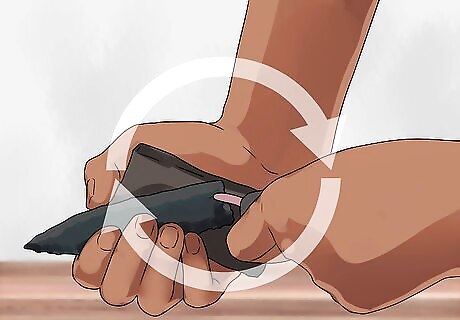

Learn how to hold the pressure flaker. If your pressure flaker is long enough, rest it against your hip for more leverage. Let your other hand, holding the flake, rest against the inside of your leg. Try not to flex the elbow of the hand holding the flake; rather, use the inside of the leg for stability, with a little extra strength from the wrist. Hold the pressure flaker just above center, and the wood will flex and push down into the flake for you. Apply pressure to the lower side of the flake, not the upper. The slower and longer you apply pressure, the longer your flakes will be. Do not bend either wrist while knapping.

Pressure flake around the entire edge of the flake. Now that you're down to the main flake or "preform," take off additional, smaller flakes using the pressure flaking method. Make a flake, flip the preform over, then make another flake along the same edge, but on the opposite face. This lets you inspect each flake after you make it, and make adjustments for irregularities or mistakes. The end result should be a "bifacial edge" with a row of scalloped marks on each side. For this first pass, remove short flakes with relatively fast pressure. Most beginners find it easier to make short flakes than long, so this shouldn't be an issue. This is the longest, most difficult part of a flint knapping project. Take it slow, and accept that you may break a few flakes while learning.

Abrade the edge. Never make two flakes in the same place without abrading in between, just as described in the abrasion step above. The closer you get to the finished product, the less heavily you will have to abrade, as you are working towards the final product of a delicate, razor sharp edge and point.

Sharpen your pressure flaker periodically. The copper or antler tip will wear down quickly, so sharpen it several times during the creation of a single tool, using a knife or a stone to scrape the edge. Many knappers pound the copper tip flat to a thin chisel shape to sharpen it and change the behavior of the tool slightly. You can try it at this point to see if you prefer the chisel to the point tip.

Repeat until you reach the desired shape. After abrading, repeat the same pressure flaking process. On the next few circles, try to use slower, more prolonged pressure to create longer flakes, in order to thin the tool right up to the raised convex center. Remember to abrade after each full circle. Once the final shape is complete, which may require some focused attention on certain areas, do a final run of pressure flaking. For most tools, you do not abrade the edge after you finish, leaving it sharp for use as a cutting or piercing tool. Most commonly, you would use longer flakes near one end to taper it gradually to an arrow or spear point, while the other end is shaped through smaller flakes into the wider base. Experienced knappers can make long flakes quite quickly, but it takes a lot of practice to get to that point. One of them recommends pointing the pressure flaker at the opposite edge (away from your hand), quickly building up to maximum pressure, then rotating the hand holding the preform slightly until the flake pops off.

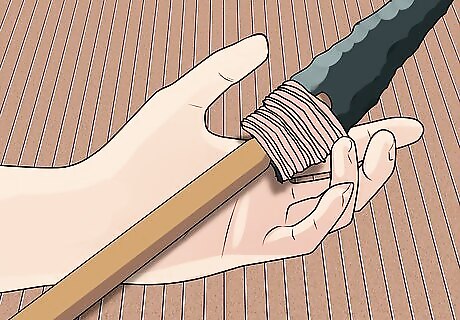

Make a notch or stem (optional). You may put the finishing touches on a point by notching the base or forming a stem at the base. This is a difficult skill to learn, and many beginners break their first tool or severely alter the shape. Still, if you plan on tying the tool to an arrowhead or handle, this is a necessary step. Hold your finished tool flat and press the tool at a steep angle and high pressure through the entire tool. Flip the tool over and repeat to extend the notch, then use gentler pressure to trim it flat. While you can use your pressure flaker, a flattened steel nail in a wooden handle makes a better notching tool, as the harder metal focuses the energy to a smaller area. Grind the inner edge of the notch before tying it onto anything, to prevent it cutting the string.

Comments

0 comment