views

Reducing Anxiety over Stuttering

Understand how stuttering works. When a person stutters, the stuttering may completely block their speech, cause them to repeat sounds, or cause them to "stick" on one sound for too long. During a block, the vocal chords push together with great force, and the person is unable to speak until the tension is released. Becoming comfortable with the stutter and practicing the following techniques will make this tension less severe. While there is no cure for stuttering, these techniques will help you reduce it to manageable levels until it is a much smaller obstacle. People with stutters have won awards in such speech-reliant fields as sports commentary, TV journalism, acting, and singing.

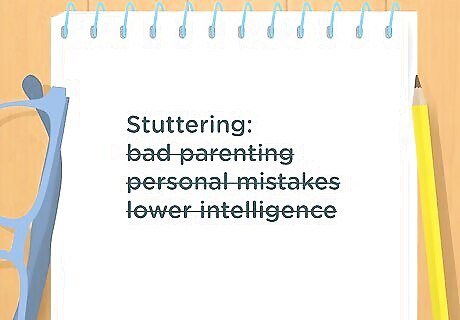

Step outside of your shame. Stuttering has nothing to do with lower intelligence, personal mistakes, or bad parenting. It does not mean that you are an especially nervous or anxious person, just that you are exposed to stuttering situations that could make anyone nervous. Realize that your stutter has nothing to do with who you are as a person. It's normal to feel ashamed, but understanding that there's no rational reason behind it may help you feel shame less often and less painfully.

Practice speaking in front of supportive people. Most likely your friends and family know you stutter, so there's no reason to feel anxiety about "revealing" your stutter to them. Be open about the fact that you'd like to practice your speaking, and read aloud to them or make an effort to join a conversation. This is a good step to take, and one that supportive friends should support if you let them know what you're doing.

Stop avoiding speaking situations. Many people who stutter try to hide the fact, either by avoiding certain sounds, or by avoiding stressful speaking situations entirely. You don't need to go out of your way to speak around bullies, but try not to hold back or switch to safer words when talking to friends, supportive family members, and strangers. The more conversations you hold while stuttering, the more you'll realize that it doesn't hold you back or bother other people nearly as much as you may think.

Address the behavior of people who tease you. Bullies are one thing; they are trying to get you irritated or upset, and it's best to ignore them or report their behavior to people in authority. Friends, on the other hand, are supposed to support each other. If a friend teases you about your stutter in a way that makes you anxious, let them know it bothers you. Remind them if they slip back into old habits, and warn them that you may need to spend less time together if they continue to cause suffering.

Join a support group for people who stutter. Search online for a stuttering support group in your area, or join an online forum. As with many challenges, stuttering can be easier to deal with if you have a group of people who share their experiences. These are also excellent places to find more recommendations about managing your stutter or reducing your fear of stuttering. National stuttering associations exist in India, the United Kingdom, and many other nations.

Don't feel the need to cure your stutter completely. A stutter rarely goes away entirely, but that doesn't mean you've failed to control it. Once you're functioning with minimal anxiety in speaking situations, there's no need to panic when your stutter briefly becomes more severe. Reducing your anxiety will help you live with a stutter and minimize the amount of stress it causes.

Managing a Stutter

Speak at a comfortable pace when you are not stuttering. There is no need to slow down, speed up, or otherwise alter your speech patterns while you are not actively stuttering. Even if you only speak without interruption for a few words at a time, speak them at your normal rate instead of trying to alter your speech patterns to avoid a stutter. It's more effective to relax and focus on what you're saying, rather than tense up and focus on how you say it.

Take all the time you need to get through a stutter. A major source of anxiety, and a major reason some people who stutter, is the feeling that you need to push through a word immediately. In fact, slowing down or pausing when you reach a stuttering obstacle can train you to speak more smoothly and with less anxiety.

Keep your breath flowing. When you get hung-up on a word, your initial reaction will be to hold your breath and try to force the word out. This only worsens the stuttering. You need to focus on your breathing when speaking. When stuck in a block, pause, take a breath, and try again to say the word while gently breathing out. When you breathe, your vocal chords relax and open up, allowing you to speak. This is easier said than done, but may become easier with practice.

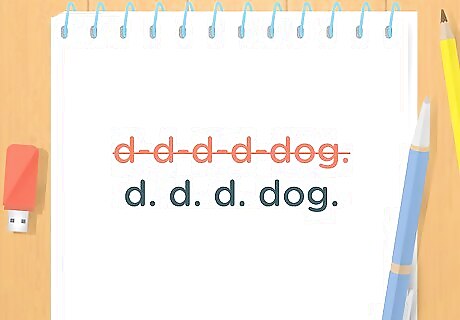

Practice fake stuttering. Paradoxically, you can help yourself manage your stutter by intentionally repeating difficult sounds. If you're anxious about the times when you can't control your speech, make the sounds deliberately to regain that control. Saying "d. d. d. dog." feels different than stuttering "d-d-d-dog". You're not trying to force your way through to the full word. You simply say the sound, making it clear and slow, then continue on to the word when you are ready. If you stutter again, repeat the sound until you feel ready to try again. This can take a lot of practice to become comfortable with, especially if you are used to hiding your stutter instead of accepting it. Practice to yourself first if necessary, then work your way up to using this technique in public.

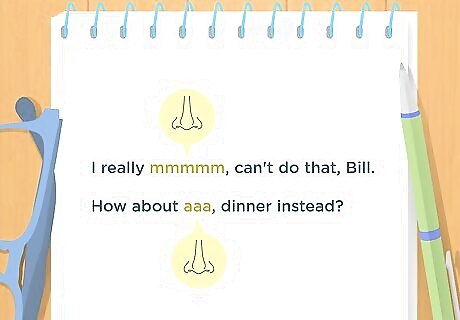

Lead up to an obstacle with an easier sound. A common experience among people who stutter is the feeling of a "wall" or obstacle that they know is coming up at a certain sound. Make this obstacle easier to surpass by leading up to it with a sound you have no problems with. For instance, making a nasal "mmmm" or "nnnnn" sound may help you "sneak past" a difficult hard consonant such as k or d. With enough practice, this may make you confident enough to say the difficult sounds normally, and just keep this trick in your bag in stressful situations. If you have trouble with m and n sounds, you might try an "ssss" or "aaa" sound instead.

Consult a speech therapist. Hiring a speech therapist to assist you can greatly reduce the effect stuttering has on your life. As with the other techniques described here, the exercises and advice a speech therapist may develop for you are intended to help you control your stuttering and minimize its impact on your speech and emotions, not eliminate it entirely. It may take a lot of practice to use these therapy techniques in the real world, but with patience and realistic explanations, you could improve your speech greatly. If advice or exercise is not working for you, try to find another therapist. More old-fashioned therapists may advise slowing down your speech, or suggesting other exercises that many modern researchers and people who stutter find counter-productive.

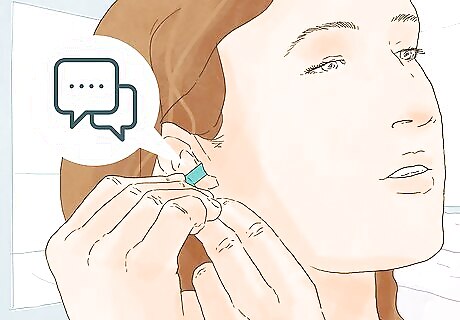

Consider an electronic speech aid. If your stuttering still causes you severe anxiety, you could purchase an electronic feedback device, a special device which allows you to hear yourself differently and with a delay. However, these devices can cost thousands of U.S. dollars, and are not a perfect solution. They can be tough to handle in loud environments, such as social gatherings or restaurants. Keep in mind that these devices are useful as an aid, not a cure, and it is still useful to practice anxiety reduction techniques and consult a speech therapist.

Helping a Child who Stutters

Don't ignore the stutter. Many children develop a stutter in their first few years of speaking, but while many of them lose the stutter within a year or two, this does not mean you shouldn't help them through it. Speech therapists who are not up to date on modern research may recommend "waiting until it goes away," but it is a far better idea to be conscious of the child's stutter and follow the steps below.

Slow down your speech slightly. If you tend to be a fast speaker, it's possible the child may be copying you by speaking too fast for their language abilities. Try slowing down your speech just a little, keeping a natural rhythm, and make sure you speak clearly.

Provide a relaxed environment where the child can speak. Give the child time to speak at a time and place where they are not being teased or interrupted. If the child is excited about telling you something, pause what you are doing and listen. Children who do not feel they have a place to speak may feel more anxiety over their stutter or become less willing to talk.

Let the child finish their sentences. Increase the confidence of the child by listening in a supportive way while they speak. Don't try to finish their sentence for them, and don't walk away or interrupt when they stuck.

Learn about providing parental feedback. A relatively modern type of stuttering treatment for children is a system of parental feedback, such as the Lidcombe Program developed in the 1980s. In these systems, a therapist trains the parent or caretaker to assist the child instead of enrolling the child in a therapy program directly. Even if you cannot find a suitable program near you, you can benefit from some of the tenets of this program. Talk to the child about the stutter only if the child wants to. Compliment the child when they speak without stuttering or have a day with lower levels of stuttering. Do this once or twice a day at consistent times, rather than making a big deal of the stutter by repeating the praise often. Rarely give negative feedback by pointing out the stutter. Don't do this when the child is upset or frustrated.

Comments

0 comment